The timeworn metaphor has been used and reused ever since the earliest days of the Trump era, when Donald Trump was first putting together his cabinet. On December 4, after he named James Mattis to be his defense secretary, the website Politico asserted that “there’s finally an adult in the room.” In January, as Rex Tillerson was being confirmed as secretary of state, Bob Corker, chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, told his colleagues, “To me, Mr. Tillerson is an adult who’s been around.” In February, during Trump’s first visit to Mexico, the Financial Times quoted one source as saying that Tillerson and John Kelly (then secretary of homeland security) “represent the adult wing of the new regime.”1

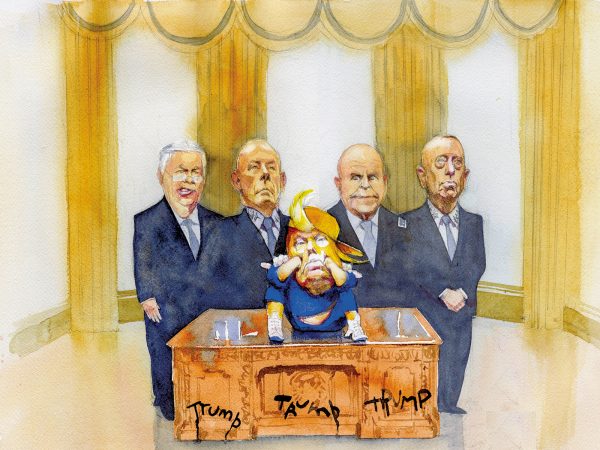

Before long, the metaphor became a collective one: a small group of officials within the Trump foreign-policy team represented “the adults” or “the grownups in the room.” The membership in the club changed slightly from time to time. At first, the “adults” honorific was most commonly applied to the threesome of Tillerson, Mattis, and National Security Adviser H.R. McMaster. This summer, after Trump brought in Kelly to be his White House chief of staff, Kelly became not only a member but the leading figure in the Adults club, while, gradually, Tillerson’s problems and increasing marginalization as secretary of state have made him less central to the group.

Phrases like “the adults” or “the grownups in the room” seem on the surface to carry intuitive meanings but raise all sorts of questions that deserve scrutiny. What does it mean to be an “adult” in Washington in general, or, in particular, under Donald Trump? What policies do the “adults” favor? Where do they come from, and what do they believe? Most importantly, what is the significance of the fact that most of Trump’s so-called grownups come from the military? To answer such questions, it helps to look at the history, both of the way the idea of “adults” has been used in Washington in the past and of the way military officers in the US have served in top civilian jobs.

The notion that some officials are “adults” or “the grownups in the room” is an old Washington trope dating back decades before the arrival of Donald Trump. It is linked to an opposing metaphor: in Washington parlance, others are said to be “in need of adult supervision.” These phrases go to the heart of the way those who work in Washington operate, see themselves, and, above all, talk about themselves. Washington insider newsletters like The Nelson Report and Washington columnists like The New York Times’s Thomas Friedman purvey the notion that some people are “adults” or “grownups” and others are in need of “adult supervision.” The phrases were meant to imply a judgment about an individual’s character or behavior: some people were deemed to be mature, while others were merely being juvenile.

Before Trump, this Washington lingo was usually a cover for policy differences. The “adults” were those who favored certain policies or approaches; those in need of “supervision” were the opponents of such policies. Thus, the metaphors amounted to a verbal sleight-of-hand, transforming political judgments into personal ones. Other, more neutral adjectives could usually have been applied to those who were approvingly called “adults” (“pragmatists,” “centrists,” and “moderates” come to mind), but the “adults” metaphor added an extra bit of sneer and insult to the opposing side.

The “adults” were usually those who didn’t stray too far from the political center, however that was defined at the moment. Bernie Sanders has never qualified as an “adult” in the Washington usage of the word, although he is old enough to collect Social Security; nor did Ralph Nader; nor did Rand Paul, though he is old enough to perform eye surgery. What made them deficient was not their character or their immaturity, but their views.

Following the arrival of Donald Trump in the White House, the meaning of the words “adult” and “grownup” has undergone a subtle but remarkable shift. They now refer far more to behavior and character than to views on policy. This is where Kelly, McMaster, Mattis, and (to a lesser extent) Tillerson come in; “grownup” is the behavioral role that we have assigned to them.

For the first time, America has a president who does not act like an adult. He is emotionally immature: he lies, taunts, insults, bullies, rages, seeks vengeance, exalts violence, boasts, refuses to accept criticism, all in ways that most parents would seek to prevent in their own children. Thus the dynamic was established in the earliest days of the administration: Trump makes messes, or threatens to make them, and Americans look to the “adults” to clean up for him. The “adults,” in turn, send out occasional little public signals that they are trying to keep Trump from veering off course—to educate him, to make him grow up, to keep him under control. When all else fails, they simply distance themselves from his tirades. Sometimes such efforts are successful; on many occasions, they aren’t.

The back-and-forth between Trump and the “adults” has been evident on matters both big and small. Sometimes these involve questions of symbolic significance concerning the role of the president: when, at Trump’s first cabinet meeting, officials took turns in front of television cameras thanking Trump and singing his praises, as if the president were a Central Asian dictator, Mattis opted out, saying, “It’s an honor to represent the great men and women of the Department of Defense.” Sometimes these matters involve issues of sweeping importance: before Trump’s first trip to Europe, Tillerson, Mattis, and McMaster joined together to put into a draft of his speech a reaffirmation of Article V of the NATO treaty, committing the United States to the collective defense of Europe.2 Yet Trump ultimately cut the words from his speech. Then, after the understandable and predictable uproar, he turned around and made the commitment.

Trump’s blustering, threatening behavior has raised fears that he might do something impulsive, such as launch a nuclear attack. Those fears, in turn, have heightened the perception of the “adults” as watchdogs or guardians. In February, the Associated Press said that “for the first few weeks after the inauguration, Mattis and Kelly agreed that one of them should remain in the United States to keep tabs on the orders rapidly firing out of the White House.”3 Ever since, various versions of this story have appeared again and again, sometimes including McMaster or Tillerson, and usually without the time limits of the original story.

Mattis has had the (relatively) easiest time of it with Trump, while McMaster and, now, Kelly, have had the hardest, in part because of the nature of the different jobs they hold. As defense secretary, Mattis has a cabinet job that keeps him across the Potomac River, running the US government’s biggest department, and Trump seems to allow him considerably more latitude than the other “adults.”

Mattis, a former Marine Corps general who served as commander of America’s Central Command forces in the Middle East, has the satisfaction of knowing he has strong-to-intense support on Capitol Hill, where John McCain, the chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee, let it be known at the start of the administration that he would serve as Mattis’s protector. Mattis has also been especially popular within the military. Before his appointment, he said that he would speak his mind when his views differed from those of Trump. He explained, for example, why he opposes the use of torture.

With greater job security than the other “adults,” Mattis seems to have assumed the role of reminding Americans and the rest of the world that the American government existed before Trump and will survive him. At a conference in Singapore in June, when asked if America were retreating from its role in the world, he invoked a quote routinely misattributed to Churchill about America: “Bear with us,” Mattis told the audience. “Once we have exhausted all possible alternatives, the Americans will do the right thing.”

In contrast, McMaster and Kelly work at staff jobs inside the White House, where they must deal with Trump day after day. After he was appointed White House chief of staff in late July, Kelly sought to impose order, controlling who gets to see Trump and restricting what materials are given to him. But there were quickly signs that Kelly’s discipline campaign could go only so far. He could not stop Trump from saying outrageous things in public on the spur of the moment; Trump’s outburst equating the two sides in the Charlottesville protests came at what was supposed to be a press conference on infrastructure, and it left Kelly staring at the floor. It was not long before some of Trump’s friends let it be known that the president was chafing against Kelly’s restrictions. In his recent book, The Gatekeepers, Chris Whipple writes that the position of White House chief of staff “is what may well be the toughest job in Washington—so arduous that the average tenure is a little more than eighteen months.”4 At this juncture, it seems extremely unlikely that Kelly will raise the average.

As national security adviser, McMaster has had to handle especially acrimonious disputes inside the White House over issues ranging from trade and immigration to America’s role in the world. At the same time, he has had to wrestle with personnel battles that extend beyond the usual ones among cabinet secretaries. He has had to deal with various White House figures, including Trump’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner, whom Trump set up as a mini-czar over foreign-policy issues ranging from the Middle East to Mexico and China. Above all, McMaster waged a months-long battle with Stephen Bannon, the leader of the populist wing of the administration, until Bannon finally departed in mid-August.

Tillerson has been the most baffling of the “adults.” He had years of experience running one of America’s leading corporations but is serving as a classic example of why such experience does not necessarily prepare one for a top cabinet post. He came to the position of secretary of state with more establishment credentials (or at least job references) than any of the other “adults”; luminaries of past Republican administrations, such as Robert Gates, Condoleezza Rice, and James Baker all supported him. Yet Tillerson has gone further than anyone else on the foreign policy team to create a radical break with the past. His determined, prolonged efforts to pare down the State Department—by supporting budget cuts, reorganizing positions out of existence, and, above all, choosing to leave major jobs unfilled—have left the nation’s leading diplomats shocked and demoralized, wandering around the silent halls past one empty office after another. Indeed, whether intentionally or not, Tillerson has done much to carry out Bannon’s populist call of last February for the “deconstruction of the administrative state.”

BY:

BY:

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.