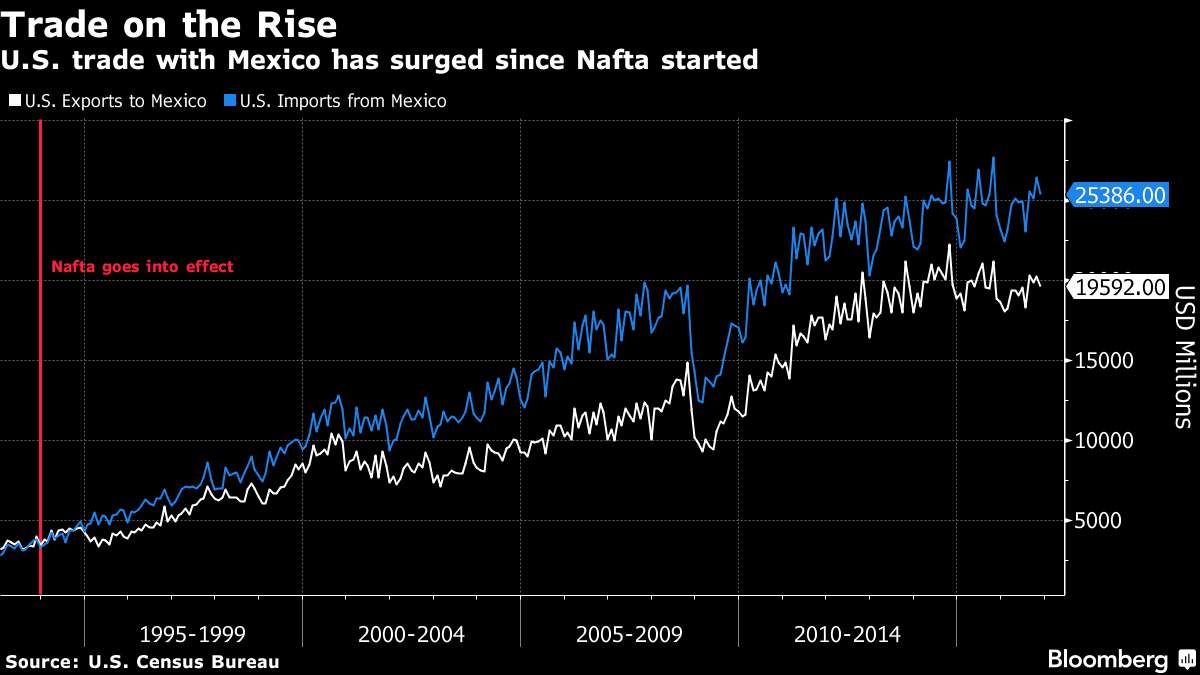

The chaos surrounding U.S. and Mexico relations continued Friday, pushing the countries closer to a trade war that threatens to spoil decades of friendship and economic cooperation.

The feud grew increasingly hostile as U.S. President Donald Trump said in a Twitter posting Friday that Mexico “has taken advantage of the U.S. for long enough” by not addressing trade deficits and security along the “very weak border.”

The tirade followed Mexican President Enrique Pena Nieto’s decision Thursday to scrap his trip to Washington after Trump said he’d follow through on campaign pledges to rewrite the North American Free Trade Agreement and charge Mexico to build a border wall. The Trump administration retaliated against Pena Nieto’s cancellation by floating the idea of imposing a 20 percent tax on all Mexican imports.

“This is a very bad day for U.S.-Mexican relations — the worst day in memory,” said Michael Shifter, president of the Inter-American Dialogue in Washington. “There is the real risk of things spiraling out of control.”

The Mexican peso plunged and the clash slowed gains in the U.S. stock market amid growing concern that one of the world’s largest trading relationships was headed for divorce.

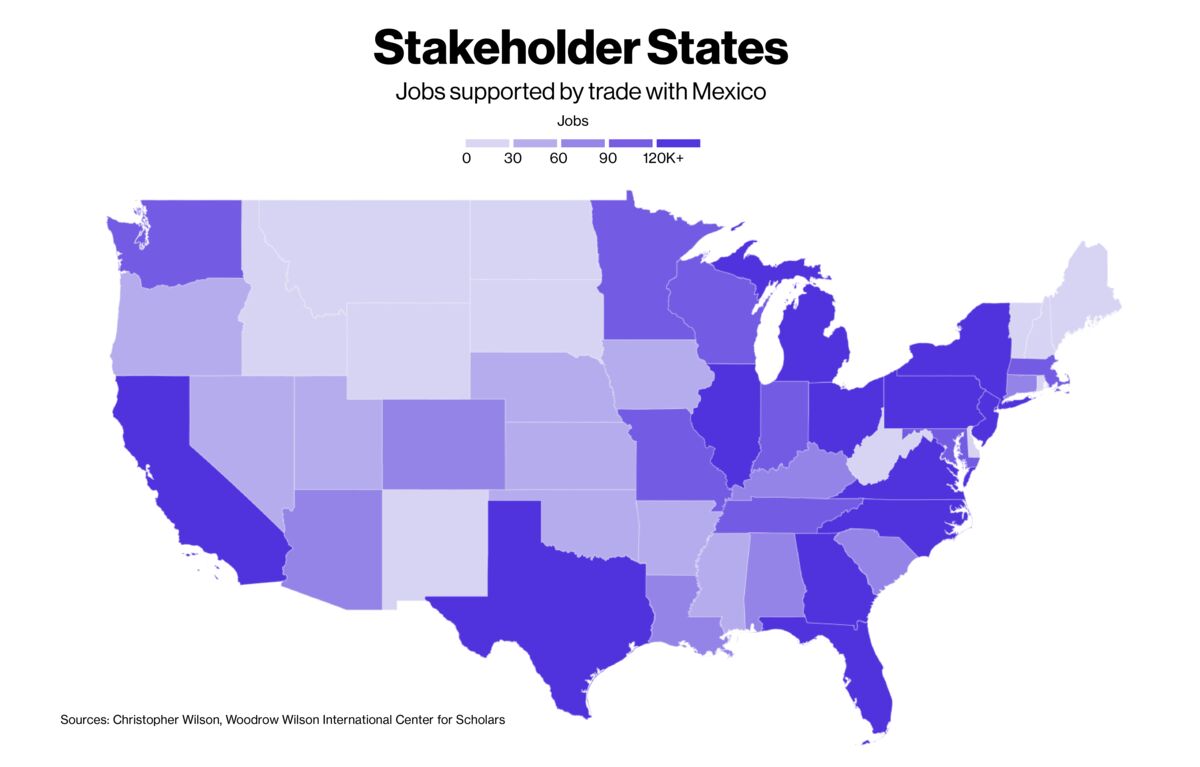

For all of Trump’s complaints about Mexico, the two nations’ economies are deeply intertwined, especially in the border states — so much so that it might be nearly impossible to pull them apart without serious political or economic unrest.

Cars, auto parts, farm goods, textiles and food all flow freely back and forth — and any move to disrupt that could cause economic harm on both sides of the border, including in the Rust Belt industrial states that propelled Trump to the presidency.

Automakers would be the hardest hit, as Ford Motor Co., General Motors Co. and Fiat Chrysler Automobiles NV have assembly plants in Mexico. Several foreign automakers also have Mexican factories that export vehicles to the U.S., including Honda Motor Co. Ltd., Volkswagen AG and Mazda Motor Corp. Other American companies that benefit from Nafta include Whirlpool Corp. and General Electric Co.

“If all imports in the first 11 months of 2016 had been charged a 20 percent duty, U.S. importers would have paid about $54 billion in tariffs, far more than some of the higher estimates for the wall’s cost of $15 billion,” Bloomberg Intelligence analyst Caitlin Webber said in a note Friday.

It’s not just trade, but national pride at stake, for both nations.

‘One-sided Deal’

Before pulling out, Pena Nieto was expected to begin talks in Washington next week on Nafta, which Trump has threatened to abandon if he cannot strike a better bargain for U.S. workers. “It has been a one-sided deal from the beginning,” Trump said Thursday on Twitter.

Simply put, any policy proposal which drives up costs of Corona, tequila, or margaritas is a big-time bad idea. Mucho Sad. (2)

— Lindsey Graham (@LindseyGrahamSC) January 26, 2017

While the Mexican leader has expressed a willingness to negotiate portions of the agreement, he has remained steadfast in refusing Trump’s demands that his country foot the bill for a border wall.

Trump adviser Kellyanne Conway tried to play down the dispute. “The relationship was not imploded,” she said on Fox News Friday. “This one meeting has been canceled and that was a mutual cancellation.”

Former Mexican President Vicente Fox in an interview with MSNBC disputed that the cancellation was mutual, saying it was Pena Nieto’s decision. He also told CNBC Friday that corporations — and ultimately American consumers — will end up paying the 20 percent import duty if the Trump administration goes ahead with the plan.

Trump this week signed a directive to start the process of constructing the wall, saying he would find a way to recoup the cost from Mexico at a later date. White House Press Secretary Sean Spicer on Thursday signaled the U.S. could raise $10 billion a year by slapping a 20 percent tax on Mexican imports, which would “easily pay” for the wall’s construction, he said.

Later, Spicer summoned reporters to his office and said the tax was only one idea to finance the wall, and that its economic impact would have to be examined.

A border tax, which would require congressional approval, would be a clear violation of Nafta, which allows the duty-free movement of goods between Mexico, the U.S. and Canada. Trump could impose 15 percent duties temporarily on Mexican imports, claiming a “balance payments emergency,” but that would fall short of the punishment his press secretary threatened.

Any new tax — and ultimately a trade war, if it came to that — would be unpopular with some members of Trump’s own party given the potential to inflict economic damage on both sides of the border. Mexico is among the biggest importers of U.S. agricultural products and assemblers of parts that are used to make American automobiles. Senator Lindsey Graham, a Republican from South Carolina, said on Twitter that “any tariff we can levy they can levy,” calling such a move a “huge barrier” to economic growth.

‘Incredible’ Recession

If Trump does decide to withdraw from the 23-year-old trade agreement, industries in both countries could suffer and the U.S. could enter “an incredible economic recession,” according to Jason Marczak, director of the Atlantic Council’s Latin America Economic Growth Initiative.

“Over the last two decades, U.S.-Mexico commercial relations have deepened across both countries,” he said.

The interdependence is most evident in manufacturing supply chains, where parts coming from the U.S. or Canada are often assembled in Mexico, where the cost of labor is cheaper.

This has led to a blurring of economic lines between the three countries. About 40 percent of the content of Mexican exports to its northern neighbor actually originate in the U.S., according to a 2010 National Bureau of Economic Research working paper.

And roughly 5 million American jobs depend on trade with Mexico, according to Christopher Wilson of the Mexico Institute at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. The positions are spread across many states and industries, from car-parts factories that supply Mexican auto plants to U.S. farms that grow the barley that goes into Mexican beer.

But most economists agree the automobile industry would be among the sectors most affected by a trade war between the U.S. and Mexico. The flow of Mexico-made passenger cars and light trucks into the U.S. reached more than 2 million vehicles in 2015, when Mexico became the largest source of imported autos, according to data from the International Trade Administration, part of the U.S. Department of Commerce.

Some 1.58 million Mexican-made passenger vehicles worth $29.4 billion were imported in the first nine months of 2016, the latest data available.

“Mexico is easily the most important country for the U.S.,” said Antonio Ortiz-Mena, a senior adviser at Albright Stonebridge Group who worked with Mexico’s original Nafta negotiating team. “The U.S. and Mexico are inter-dependent countries. If they cooperate, they are both better off. If they don’t cooperate, they are both worse off.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.