By: Erika Solomon , Beirut

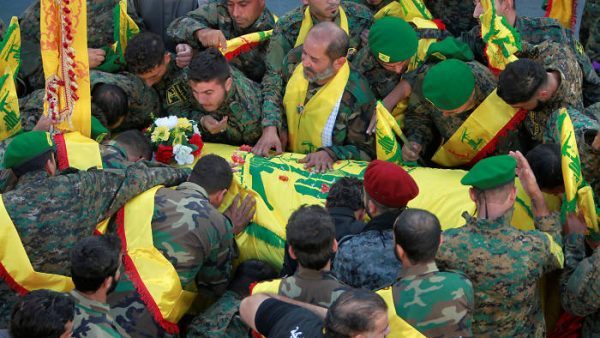

As mourners carried the coffin of a slain Hezbollah commander, they moved quickly to wipe away blood still dripping from his body — it had been washed in haste as it was rushed from the battlefields of Aleppo to its final resting place in Lebanon.

While Russian war planes and bombs have dominated headlines about outside intervention in Syria’s five-year conflict, thousands of those fighting on the ground in support of President Bashar al-Assad are just as foreign. They are part of a large and growing force of Shia militias hailing from Lebanon, Iraq, Iran and beyond that see the war as both an ideological and regional struggle against Sunni rivals.

The foreign Shia militants have typically tried to keep their activities in the shadows, but they have become increasingly bold in showcasing their role in the conflict. Iran, Mr Assad’s staunchest backer in the war, this week said 1,000 of its men have died in Syria in a highly unusual announcement that put attention on a military role it has shrouded in secrecy.

A week earlier, Hezbollah, a Lebanese militant group backed by Iran, shared photographs of a massive “military parade” not at home, but across the border on Syrian soil.

When the Hezbollah commander’s funeral procession moved through his mountain village near Beirut last month, some relatives quietly questioned whether their loved ones should be fighting in a foreign country. But others loudly praised his role the battle for Aleppo, the besieged northern Syrian city.

“It could not be helped,” one relative told a Financial Times reporter at the funeral. “Had they not gone to Syria, Isis would already be here and have butchered us all.”

Syria’s uprising against four decades of Assad family rule began in 2011, but quickly devolved into a sectarian conflict as Syria became a locus for ideologically motivated foreign fighters.

The myriad armed groups that joined the fight also reflect regional power struggles between predominantly Shia Iran and Sunni-run nations like Saudi Arabia, Turkey and Qatar and Saudi Arabia that is playing out in Syria. The Sunni states give arms and other support to the Syrian rebels, while Tehran backs some of the Shia militia.

The rebellion, led by Syria’s Sunni majority, emboldened Islamists who came to dominate the uprising and attracted an influx of radical foreign militants empowered al-Qaeda’s local branch and its splinter group, Isis. Shia militias flocked to the side of Mr Assad, a longtime Iran ally and member of Syria’s Alawite minority sect, which has links to Shia Islam.

Shia militants first justified their presence as a need to defend holy Shia shrines and areas that threatened their own security — such as Hizbollah’s intervention along the porous Syrian-Lebanese border. Iran’s elite Revolutionary Guards Corp has officially said it has sent an unspecified number of “military advisers” to back the regime. But many observers believe Tehran is also using the conflict to extend its influence in the region.

Phillip Smyth, a researcher at the University of Maryland and author of the blog “Hizballah Cavalcade,” cites the emergence of a Syrian branch of Hezbollah as an example. The group now mans checkpoints in parts of Damascus, the capital, raising the Syrian Hezbollah flag overhead.

“The broader impact of Syrian Hizbollah’s growth is that Iran cannot only put its foreign fighters into Syria, but build a lasting influence in the country — one that even Assad would have trouble dislodging,” says Mr Smyth.

He estimates that Syria hosts somewhere between 15,500 and 25,000 Shia foreign fighters. On the other side, an estimated 27,000 Sunni foreign fighters are believed to have joined jihadist groups since the war erupted.

But Sunni foreign fighters numbers are dropping because Turkey has tightened its border with Syria, while the flow of Shia militants continues unabated.

The regime’s latest offensive on Aleppo, which is currently divided between the government in the west and rebels in the east, highlights the growing role of the militias. Some estimates suggest about 5,000 men fighting for Mr Assad in the city — a critical battleground of the conflict — are not his compatriots but Iraqis, Lebanese, Iranians, Afghans and Pakistanis.

It is widely speculated the reason for this is a dearth of Syrians to recruit to the military, as men avoid conscription and many flee the country.

For those coming from Iraq, economic motivations may have overtaken ideological ones.

In impoverished Shia neighbourhoods of the southern city of Basra, home after home is decked with a flags marking the homes of martyred fighters. While most died fighting for Hashd al-Shaabi, a local paramilitary force, in battles with Isis in Iraq, those in financial hardship say the choice is clear: join the conflict in Syria.

“There is an acceptance to an unnatural degree not just [to fight] for the Hashd, but also jihad in Syria, because they get a lot of money,” says Ali, 23, who says at least one of his cousins went to fight in Syria.

“Today guys are going in really big numbers because they are supposed to get paid about $1,300,” for a 45 to 55 day deployment in Syria, he says.

Basra residents say recruiters frequent their areas, and say some offers now extend to Yemen, where Houthi rebels with loose ties to Iran are fighting forces loyal to a government in exile, which is backed by Saudi Arabia.

For Ali’s cousin, a taxi driver, one trip fighting in Syria was enough to meet his financial needs. But the concept still appals him. “It is a choice for these guys … but it also seems like human trafficking,” he says.

FINANCIAL TIMES

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.