BEIRUT , Lebanon — After more than two years of relentless conflict, Syria’s government is desperately trying to avert a secondary crisis: a sharp decline in the Syrian currency, which is adding to the country’s economic woes.

BEIRUT , Lebanon — After more than two years of relentless conflict, Syria’s government is desperately trying to avert a secondary crisis: a sharp decline in the Syrian currency, which is adding to the country’s economic woes.

The war and the Western economic sanctions that have accompanied it have taken an inevitable toll. The Syrian economy has shrunk by 35 percent as industrial production has stalled, nearly half the population is unemployed and foreign currency reserves have been decimated, according to the United Nations, which estimates the overall impact on the economy to be as much as $80 billion.

Meanwhile, a sharp decline in the value of the Syrian pound has left residents wondering whether their savings will be rendered worthless.

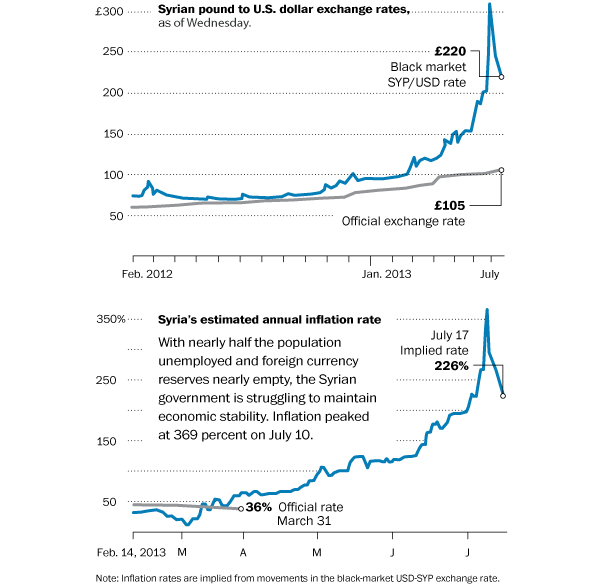

The Syrian pound, valued at 47 to the dollar before the conflict began, dipped last week to 315 against the dollar on the black market, prompting the government to announce emergency measures. A new lawwould impose a minimum sentence of three years for exchanging money without a licence, while exporting food items overseas has been deemed illegal.

The Syrian pound, valued at 47 to the dollar before the conflict began, dipped last week to 315 against the dollar on the black market, prompting the government to announce emergency measures. A new lawwould impose a minimum sentence of three years for exchanging money without a licence, while exporting food items overseas has been deemed illegal.

“The money that I saved used to mean security, but with the fall of the pound against the dollar, it means nothing now,” Abu Hashim, a 52-year-old Damascus resident whose family owns several shops, said in a phone interview.

The businessman, like many Syrians, is faced with a quandary: whether to convert his savings into dollars and cut his losses or hope that the pound bounces back.

“I honestly don’t know what to do,” he said. “I don’t want to keep money in the pound, as I’m scared it might fall again, but I don’t want to sell hard-earned money for quarter the value I got it for.”

The official exchange rate, currently 105 pounds to the dollar, is generally ignored by currency traders. A government intervention last week to buy Syrian pounds from money exchanges at 250 to the dollar, much closer to the black-market rate, appears to have injected some stability.

In a statement last Thursday, Prime Minister Wael al-Halki said the move would bring the rate back to “acceptable levels.” The pound had recovered to 220 to the dollar on Wednesday, but exchange dealers said they doubt that government strategy can do much in the long term.

“No matter how many different solutions you use to fix it, it might not be enough,” said Samer Kantakji, chairman of Syria’s Islamic Business Research Center and general manager of the exchange company al-Adham.

“Production has halted. This financial situation won’t get better if the bleeding does not stop and production does not return,” Kantakji said.

A ban on oil imports to the European Union is estimated to cost Syria’s economy $400 million a month, while tourism, which accounted for 12 percent of the gross domestic product before the war, has collapsed.

Damascus residents say that some army checkpoints in the capital are demanding that passersby present papers to show that they have paid their utility bills, as state companies attempt to stem losses.

Dwindling agricultural output, with farmers in some areas simply unable to get out to harvest, and problems in distribution also are having an effect.

Staples such as bread are subsidized by the government, but the costs of other goods are fluctuating wildly.

“The prices have gone mad,” Abu Hashim said. “In my son’s shop, yesterday we sold six eggs for 40 Syrian pounds; today, six eggs are 60 Syrian pounds. I remember two years ago when you would get six eggs for 12 Syrian pounds.”

With economic instability threatening to cost President Bashar al-Assad support, the government announced new products that would be added Monday to a list of subsidized items, including vegetable oil. The government has also promised public-sector pay raises, putting more pressure on its coffers. Analysts say that even withgenerous credit lines from Russia, China and Iran, the Syrian government will struggle to finance expenditure without printing more money.

“Once the foreign gifts dwindle, with more and more government expenditure, they are going to be in serious trouble,” said Steve Hanke, a professor in applied economics at Johns Hopkins University and an expert in troubled currencies.

Using calculations from currency data, Hanke, who is also a senior fellow at the Cato Institute, argues that the Syrian economy entered hyperinflation this month, with an implied monthly inflation rate of above 90 percent. He says that if the inflation levels are sustained for another month, he will add Syria to his list of just 56 countries that have ever had hyperinflationary episodes.

However, others say it is impossible to tell because of the lack of reliable data on the real economy and the fragmentation of the Syrian economy.

“There is no national economy at this point to extrapolate any sort of trend across the country,” said Ayham Kamel, a Middle East analyst with Eurasia Group. “Inflation and access to goods depends on the region, the nature of rebel groups present in that area, government force presence, degree of hostilities and nature of supply line.”

Coming during Ramadan, the Muslim holy month in which daytime fasting is followed by elaborate evening meals, the spike in prices has been particularly difficult for Syrians. Although some say they are determined to keep the Ramadan traditions alive, others say that has not been possible this year because of the economic woes.

“People used to invite all friends and family for the first day of Ramadan, but this year it’s barely heard of,” said Sarah, a 22-year-old resident of Damascus’s Bab Touma neighborhood, who did not disclose her last name for security reasons. “The rituals and traditions of Ramadan are not being practiced.”

Washington Post

Photo: This Syrian 50 pound banknote was worth more than one US Dollar before the March 2011 uprising against the regime of president bashar al Assad , but on July 17 six of these banknotes were worth one Dollar on the black market. Inflation reached 359 % on July 10 .

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.