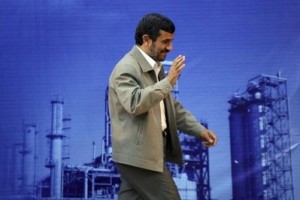

Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad makes his final appearance at the United Nations this week as a leader vilified abroad and with dwindling popularity at home.

Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad makes his final appearance at the United Nations this week as a leader vilified abroad and with dwindling popularity at home.

With nine months left before his final term expires, Ahmadinejad, 55, presides over an economy hobbled by European and U.S.-led sanctions and a currency collapse that’s firing inflation. As Israel repeatedly warns that it may bomb Iran to stop it getting atomic weapons, Ahmadinejad’s last speech to the UN on Sept. 26 may highlight his growing isolation.

“There is a high probability that he will leave Iran in somewhat of a disgraced fashion, in terms of what he has done for the country,” says Hooman Majd, author of ‘The Ayatollahs’ Democracy: An Iranian Challenge’ and an interpreter for Ahmadinejad on some of his previous UN trips.

Ahmadinejad’s rhetoric has heightened Israeli concerns that a nuclear Iran may attack, and encouraged the U.S. and allies to tighten sanctions on a country that was until last year the Middle East’s second-biggest oil producer. As his term ends, Iran’s ruling elite will have to decide whether to promote another firebrand or push candidates with views closer to former presidents Mohammad Khatami, 68, and Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, proponents of less confrontational relations with the West.

“If we had a president who knew more about politics, at least our foreign policy and our country’s image on the international scene would be better,” Javad Nasiri, 64, a retired statistical clerk, said in an interview in Tehran.

Holocaust Denial

While Ahmadinejad, who came to power in 2005, didn’t start the nuclear program and doesn’t make key decisions about it, his denial of the Holocaust has helped turn Iran into a pariah in Europe and the U.S. Their diplomats walked out of the UN’s 2010 General Assembly hall after Ahmadinejad said the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks possibly were orchestrated to bolster the U.S. economy and “save the Zionist regime.”

The European Union has since July banned purchases of Iranian oil and new U.S. sanctions announced the same month targeted banks in China and Iraq that facilitated transactions on behalf of Iran. Ahmadinejad’s rhetoric is cited by Israel as grounds for a possible military strike, with Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu saying this month that Iran’s nuclear program has entered a “red zone” and must be stopped.

Tehran Bazaars

“The Iranian nuclear issue at the end of the day has become a tiresome subject,” Ahmadinejad told senior editors and television network anchors earlier today at the Warwick Hotel in New York. “Everyone knows Iran is not seeking a nuclear bomb or weapon. I believe we must stop these one-upmanship games.”

Sanctions are nevertheless hurting the economy. Prices of staples such as meat and rice have spiraled this year, pushing inflation to 23.5 percent last month, more than double the rate two years earlier. In the bazaars of Tehran, the rial has lost about half its value on unofficial currency markets.

“Iran’s economic and social situation has gotten worse and worse in the past eight years,” said Ali Mohammadi-Fard, 32, a Tehran-based salesman at a heating systems company.

Ahmadinejad counters that the country will survive the sanctions and predicted the downfall of the European Union.

“We don’t see sanctions as a fundamental problem,” he said in New York today. “We will put it behind us. Conditions in Iran are not as bad as portrayed by some. In the five years that sanctions have been ratcheted up, we believe the EU is on the verge of disintegration and collapse.”

Electoral Guessing

The thrust of Iran’s nuclear policy is likely to remain intact no matter who succeeds Ahmadinejad, said Trita Parsi, president of the Washington-based National Iranian American Council. While the president has some input into foreign and nuclear policy as a member of the Supreme National Security Council, the ultimate say goes to Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, 73.

Predicting who will succeed Ahmadinejad is difficult because candidates must be approved by the Guardian Council — a group of clerics and jurists — based on criteria including their Islamic faith and adherence to the theocracy’s principles. The two-week campaign also means candidates and platforms are introduced shortly before the vote.

Ahmadinejad, who can’t stand for a third term when the current one ends in June, was re-elected in 2009 in a vote that opponents said was rigged. Security forces clamped down on mass protests against the result, leaving dozens of dissidents dead.

Guessing Game

“In 2008, when we were nine months away from the Iranian presidential election, who would have predicted any of these things happening?” said Majd. “We didn’t even know who was going to be running,”

Some Iranian parties have started to hold discussions about which candidate to put forward. Iran’s Popular Front of Reforms in July said it consulted with Khatami andRafsanjani, who was born in 1934, one of the Islamic republic’s founders and its president from 1989 to 1997.

At the same time, Rafsanjani’s clout has waned and Gala Riani, head analyst for the Middle East at Control Risks in London, says Iran’s leadership is unlikely to back a candidate outside the conservative camp.

In 2005, Rafsanjani lost a come-back bid to Ahmadinejad and last year lost his position as chairman of the Iranian body that chooses the Supreme Leader. His daughter Faezeh was this week taken into custody to serve a six-month sentence on charges of “propaganda.”

Nuclear Pop

“The Guardian Council still has the ability to vet candidates and it’s unlikely that we will see a strong reformist,” said Riani. “The political scene has shifted so far to the right, toward the conservatives. There are quite a few candidates who could be seen as being part of the moderate end of that stance, but they are not part of reformist camps as we know them.”

Whoever wins will still be in a position to set the tone at home and abroad just as Ahmadinejad made the nuclear issue a keystone of his tenure despite the limitations of his position.

Under his presidency the country has started celebrating an annual “Nuclear Day.” Televised ceremonies have featured dancers carrying laboratory phials, and local pop singers performing pro-nuclear songs. In campaign speeches and televised addresses, Ahmadinejad lauds scientific progress as a source of national pride, then castigates the nation’s enemies for trying to deny Iran its benefits.

Caring at Home

Ahmadinejad favors “very grandiose, populist statements that were clearly designed to antagonize the western world,” Riani said. Western countries “quickly wrote him off as a president that they were unlikely to be able to engage with.”

Ahmadinejad portrays himself as caring at home and fearless when addressing foreigners. Sharing platforms with other speakers, he often smiles benignly while listening, and responses to questions are peppered with evocations of universal love and a utopian future.

That’s not helping an economy that relies on oil exports for its lifeblood. Iranian output dropped to 2.75 million barrels a day last month, from an average of 3.7 million in the past five years. In July, Iraq overtook Iran as a producer for the first time in two decades.

“I don’t think anybody can doubt that the economy is in a worse position” than when Ahmadinejad came to power, mirroring the decline in Iran’s international position, Majd said. “Some of those issues are not completely Ahmadinejad’s fault. But you have to look at the legacy of an eight-year presidency and admit that these issues are important to the average Iranian.”

Business Week/ Bloomberg

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.