By: Patrick Galey

“The glory of Lebanon” has been trumpeted for millennia, from the Bible to Gibran, via the gawping mouths of scores of explorers, artists and poets.

It’s natural beauty, at once forbidding and beguiling, has served as temptation for conquering armies, fuel for meandering fleets and refuge for religious iconoclasts.

Not so any more.

The news that UNESCO is considering removing Lebanon’s Qadisha Valley from its World Heritage list ought to jolt many governments into immediate and decisive action. In Beirut, the threat has been met with little more than political platitudes.

The stick over the Valley has been wielded by the World Heritage Center for years, with the organization formulating a range of measures in 2007 for the government to adopt in order to avert Qadisha losing its protected status.

The stick over the Valley has been wielded by the World Heritage Center for years, with the organization formulating a range of measures in 2007 for the government to adopt in order to avert Qadisha losing its protected status.

UNESCO sources have said it will not take a back seat “when you have countries turning these places into commercial projects and allowing people to violate the sites.” Exactly that is happening in Qadisha.

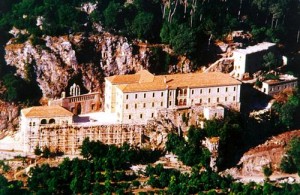

The valley – home to some of the oldest and most significant Christian monasteries in the Middle East – has become a playground for tourists and locals alike.

The hour-long trek to the Saint Marina Monastery – hewn into rock alongside the first Maronite Patriarchate – is punctuated by makeshift campsites strewn with rubbish, illegally built restaurants and stampedes of either buses carrying ‘walkers’ or quad bikes.

It is a situation repeated throughout Lebanon. Almost uniquely verdant and vertiginous in the region, tourists still flock from the Middle East and further afield to enjoy its mountain air and ancient artifacts. But little is done to preserve such attractions.

The recent prosecution of several quarry owners marks a gold star in the Lebanese judiciary’s black book of failure to penalize illegal activity on protected land.

The forest of Harissa, north of Beirut, has seen construction for a number of months on what is supposed to be a no-build zone. Beaufort and Msaylha castles in the south have had virtually nothing done to them in terms of conservation for several years. Even at the ancient ruins of Baalbeck and Aanjar – themselves ordained with World Heritage status – one can walk with impunity over stones laid hundreds of years ago.

Through all this, parliament has sat idly by. As one head of a Lebanese conservation organization put it, “Violations are happening faster than any intervention, despite the fact that when you talk to the ministers concerned, they all agree that such actions are illegal.”

It has taken three years for the Culture Ministry to notify the country’s President about the state of Qadisha. It may already be too late.

But faced with an apathetic government, civil society has taken it upon itself to keep Lebanon beautiful.

Preservation initiatives in the Chouf Mountains, the north and parts of the south have seen hundreds of newly planted trees, as well as the safeguarding of thousands of hectares of forest.

Universities in Beirut and other coastal cities have begun gratefully received plant auctions and now offer tuition on how to maintain gardens and green spaces.

A promising – if slightly farfetched – Green River Beirut Project, supported by local NGOs, is in its lobbying stage.

Last Sunday saw thousands of volunteers along the coast clean up beaches as part of a coordinated effort to make Lebanon up before the tourist season proper is upon us. Tomorrow, campaigns will descend on the ancient city of Byblos and from a human chain in an attempt to force policymakers to give a brackish nature reserve there protected status.

It remains to be seen whether any of these nascent initiatives will have the desired effect. There is, admittedly, nothing to guarantee sites’ protected status is respected (take Qadisha as an example). But the risks of doing nothing are far graver.

Lebanon has enthralled residents and visitors for generations. To continue doing so, the above programs are a promising start. Huffingtonpost

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.