Venezuelans lined up to purchase airline tickets and TVs this weekend in a bid to protect themselves from price increases after ailing President Hugo Chavez devalued the bolivar for a fifth time in nine years.

Venezuelans lined up to purchase airline tickets and TVs this weekend in a bid to protect themselves from price increases after ailing President Hugo Chavez devalued the bolivar for a fifth time in nine years.

Chavez, who is recovering from cancer surgery in Havana, ordered his government to weaken the exchange rate by 32 percent to 6.3 bolivars per dollar starting Feb. 13, Finance Minister Jorge Giordani told reporters Feb. 8. Yesterday, a sign at an electronics store in southeastern Caracas restricted customers to one purchase each as Venezuelans rushed to buy flat-screen televisions.

A weaker currency may further fuel the fastest inflation rate in the region as about 70 percent of products consumed in Venezuela are imported or assembled from raw material shipped from abroad, according to the Consecomercio trade chamber in Caracas. The move, which seeks to narrow the budget deficit, may undermine support for Chavez and his allies ahead of possible elections this year as the cost of living increases.

“Any economic measure always has winners and losers,” said Luis Vicente Leon, president of Caracas-based polling firm Datanalisis. “No one devalues for fun. If you devalue to correct a problem, there’s always going to be a price to pay.”

South America’s biggest oil producer may have to call elections if Chavez, who hasn’t been seen for two months after leaving to Cuba for health treatment, dies or steps down. Before leaving, he named Vice President Nicolas Maduro as his successor in case he was unable to continue as president.

Spending Spree

A spending spree that almost tripled the fiscal deficit last year helped Chavez, 58, win a third six-year term. The devaluation can help narrow the budget deficit by increasing the amount of bolivars the government receives from oil exports.

A spending spree that almost tripled the fiscal deficit last year helped Chavez, 58, win a third six-year term. The devaluation can help narrow the budget deficit by increasing the amount of bolivars the government receives from oil exports.

Yet the move may also quicken inflation to more than 30 percent a year from 22 percent in January, Siobhan Morden, the head of Latin America fixed income strategy at Jefferies Group Inc. in New York, said in a note to clients.

Juan Carlos Lopez, 52, said he joined a queue of 43 people at an American Airlines Inc. desk at a supermarket in eastern Caracas yesterday to see if he could still purchase summer holiday flights to Miami and New York at the 4.3 bolivar rate.

“I came because I heard American Airlines is going to raise fares by 100 percent, that’s to say, above the devaluation,” Lopez said.

Carmelo Alvarez, a salesperson at a Samsung franchise in eastern Caracas, said sales quadrupled to about 800,000 bolivars on Feb. 9 from what the store would normally sell on a normal Saturday. The government announced the devaluation ahead of a four-day holiday to celebrate Carnival.

Political Cost

“There is surely going to be a political cost, which may weigh against the Chavistas and hence be viewed favorably from the markets if it shifts protest votes to the opposition,” Morden said.

Holders of Venezuelan bonds stand to be the biggest winners as the devaluation helps close the fiscal deficit, said Robert Abad, who helps manage $48 billion in emerging-market assets at Western Asset Management Co.

Venezuela’s dollar bonds have returned 4.9 percent this year after Chavez’s deteriorating health triggered a 50 percent return in the nation’s debt last year, almost three times the average for emerging market bonds, according to JPMorgan Chase & Co.’s EMBI Global index.

The yield on Venezuela’s benchmark dollar bonds due 2027 fell 10 basis points to 8.7 percent on Feb. 8 as prices reached a five-year high of 104.53 cents.

Weaker Bolivar

The weaker exchange rate will give the central government an additional 84.5 billion bolivars ($13.4 billion) in revenue, mostly from oil sales done in dollars, according to Caracas- based research company Ecoanalitica.

Chavez increased spending in real terms by 25.5 percent in the year prior to the election in which he defeated opposition challenger Henrique Capriles Radonski by 11 percentage points, according to calculations by Bank of America Corp. That helped widen Venezuela’s fiscal gap to 11 percent of gross domestic product last year from 4 percent in 2011, according to Moody’s Investors Service.

The devaluation “is a big positive for Venezuelan credit overall — the government’s bonds and PDVSA debt,” Abad said in an e-mail from Pasadena, California, where Western Asset Management is based. Although “a devaluation improves parts of the economy while exacerbating problems elsewhere, overall it improves Venezuela’s creditworthiness.”

In the unregulated market, the bolivar weakened 6 percent Feb. 8 to 19.53 per dollar, according to Lechuga Verde, a website that tracks the rate.

Seized Stores

After devaluing the bolivar by 50 percent in January 2010, Chavez seized 41 retail stores that were majority-owned by France’s Casino Guichard Perrachon SA and threatened to nationalize others that raised prices in a bid to curb inflation.

The scarcity index, which measures the amount of goods that are out of stock on the market, rose to 20.4 percent, its highest level, according to the central bank’s inflation report published on Feb. 8.

Shares of consumer companies such as Colgate-Palmolive Co, which already felt the impact of price controls imposed last year, fell on news of the devaluation. Colgate, the world’s largest toothpaste maker, dropped 1.5 percent to $108.49 at close of trading in New York Feb. 8.

Meat Company

Copenhagen-based East Asiatic Company Ltd., whose affiliate Venezuela Plumrose is the country’s biggest meat company, said it will take 8 to 12 months to restore demand after the devaluation. The company will mitigate effects through “dynamic price management,” it said in a statement yesterday.

The central bank’s so-called Cadivi system, which sells dollars to importers at the official exchange rate, will provide $35 billion this year, bank President Nelson Merentes said. That’s the same amount Cadivi sold last year, according to a Dec. 31 central bank report. The Sitme exchange, which sold at a weaker rate of 5.3 bolivars per dollar, provided about $8 billion last year and will be closed, said Merentes.

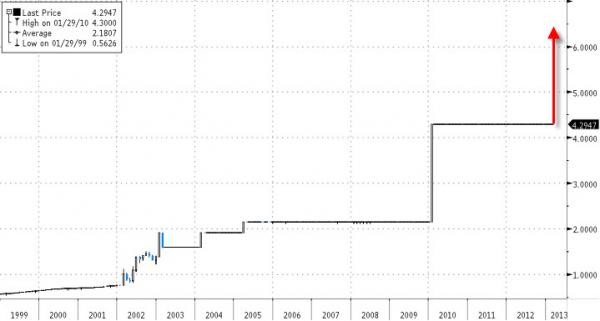

With Friday’s devaluation the bolivar has weakened 91 percent from 0.56 per dollar since Chavez took power in 1999, while oil prices have risen tenfold from $9.4 a barrel. Chavez last devalued in December 2010 when he weakened an exchange rate on so-called essential goods by 40 percent, unifying the two fixed foreign exchange rates it had at the time.

Web Purchases

Eduardo Mendez rushed to buy himself an Amazon.com Inc. gift card worth $380 on Feb. 9. Mendez, head of digital sales at a Caracas media company, said he wanted to use up a $400 allowance the government permits him to spend each year on Internet purchases before the official rate of the bolivar declined.

The rush by Venezuelans to use their foreign currency quotas before the exchange rate weakens prompted Information Minister Ernesto Villegas to calm fears by saying the old rate of 4.3 will be respected until Feb. 12.

“I had doubts about buying the card,” Mendez said in an e-mail after nabbing his card at the old rate. “But then I thought: the worst business you can do in this country is delay buying.”

SFgate

Photo: The above 1000 Bolivar banknote was worth more than $300 in 1978 now it is worth about 1.5 US cents. Several zeroes were removed from current banknotes after devaluation

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.