Many of the Gulf visitors so crucial to Lebanon’s tourism and hospitality sectors have stayed away this year as the turmoil in neighbouring Syria has sent tremors through nearby Lebanon.

Many of the Gulf visitors so crucial to Lebanon’s tourism and hospitality sectors have stayed away this year as the turmoil in neighbouring Syria has sent tremors through nearby Lebanon.

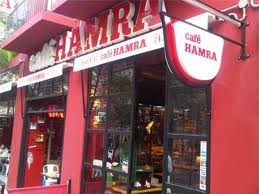

But you wouldn’t know it from walking into Cafe Hamra, a restaurant on one of Beirut’s main commercial thoroughfares. Almost every table is full.

Salim Mokbal, the manager, has an explanation. In the past six months, during which violence in Syria has intensified, he has started to see more Syrian customers. “They’re replacing the Gulf people,” he says.

Up to 28 per cent of Lebanon’s gross domestic product is estimated to come directly or indirectly from tourism, and the Syrian influx, which has been particularly marked since a rebel surge in Damascus in July, has provided respite from the empty rooms and virgin tablecloths.

It is a grim time for the Lebanese tourism industry. Even before their governments told them to avoid Lebanon in August, Gulf citizens, who account for 45 per cent of tourism spending in Lebanon, were coming in smaller numbers than usual.

In June Fadi Abboud, tourism minister, admitted that Lebanon had lost more than 300,000 Gulf tourists, who normally drive here via Syria.

The Syrians do not spend in the way that Gulf tourists did, however, and what economic boost they have given will not change the fact that the Lebanese economy is contracting.

There is no way of accurately measuring the number of Syrians who have settled in Lebanon in recent months, because people still move back and forth across the border.

More than 60,000 have registered with the UN as refugees since the start of the turmoil in March 2011, but there are also thought to be many middle class families who are at least temporarily basing themselves in Lebanon while they decide what to do. Syrian number plates are a common sight on the streets of Beirut.

Syrians usually stay in hotels for a short time before moving to a furnished apartment, industry representatives say.

Lebanon’s consumer price index jumped more than 6 per cent in July, which is almost entirely accounted for by Syrian demand on the rental market, according to Nassib Ghobril, chief economist of Byblos Bank.

Musa Abu Rached, who works at the front desk of a block of furnished apartments in Hamra, says most of his occupants are Syrians, taking rooms left vacant after Gulf visitors cancelled bookings.

“Mostly they rent by the month,” he says. “They’re not sure how long they can stay.”

They also do not consume like tourists.

“[Gulf visitors] are real spenders. They stay in hotels and do shopping. They come with a very strong purchasing power and a budget for the month they spend in Lebanon,” says Ibrahim Saif, an economic analyst at the Carnegie Middle East Center in Beirut.

“The Syrians are not behaving like tourists. There is a high degree of uncertainty. They will carefully manage their money because they don’t know how long the crisis will last.”

This analysis is borne out in a shoe shop just over the road from the furnished apartment block. In the window are spike-encrusted heels in the style of Christian Louboutin, the designer whose shoes are allegedly coveted by Asma Assad, wife of the Syrian president. But business is bad, says the manager, Michael Fakilian.

“Syrians take furnished apartments, but they don’t come here for shopping,” he says glumly.

Even allowing for a boost in the rental market caused by Syrians relocating here, the net effect of the crisis on the Lebanese economy is heavily negative, says Mr Ghobril.

“The other impact of the Syrian crisis is much more significant than the Syrians living here and spending money here,” he says.

Syria’s revolt, which has turned into a civil war, has destabilised Lebanon, and many fear worse is to come. The country has seen intense clashes between pro- and anti-Assad factions in the northern city of Tripoli and a wave of revenge kidnappings following the capture of a Lebanese Shia man in Syria. Repeated crises have been contained but the economic damage is lasting.

Moreover, the intense political polarisation afflicting Lebanon before the Syrian crisis has prevented the government from doing enough to shield the economy or stimulate growth, says Mr Ghobril.

He says there has been a decline in consumer confidence, a freeze on foreign direct investment and, in July, net deposit outflows. The latter do not indicate a panicked flight, but are a worrying indicator of sentiment.

The International Institute of Finance last week revised down its 2012 growth forecast for Lebanon to 1.2 per cent. In 2010 growth was estimated at 7 per cent.

“In my 15 years in Lebanon I have not seen the economic situation so bleak,” says Mr Ghobril. “The uncertainty of the situation is unprecedented.”

Financial Times

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.