By Jackson DieHl

By Jackson DieHl

For a year, a chorus of pundits has been proclaiming that the Arab Spring has ushered in a new era in the Middle East in which the United States no longer is the “indispensable nation” Bill Clinton once described. Syria has proved them wrong.

To be sure, so far the evidence is a negative: the failure of the United Nations or Syria’s neighbors to stop the country’s slide into civil war in the absence of U.S. leadership. The case is nevertheless conclusive — because every other power or organization that aspired to step into the vacuum left by Washington has tried and failed to deliver in Damascus.

Start with Turkey, Syria’s neighbor and former ally, which according to some was the big winner from the revolutions in Tunisia and Egypt and the turmoil elsewhere. Last year, Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan confidently dispatched his foreign minister with a message for Bashar al-Assad: Stop killing civilians, meet with your opposition, and adopt democratic reforms. Assad said he would; he lied, and went on killing. He has since repeated the maneuver with the Arab League, Russia and U.N. envoy Kofi Annan.

Erdogan, a mercurial man, was infuriated. He allowed opposition leaders, including the Free Syrian Army, to take refuge and organize in Turkey. He repeatedly suggested that he supported the creation of a humanitarian corridor or refuge in Syria — in other words, a strip of territory that would be taken over by outside powers and if necessary, defended with military force.

But there is no humanitarian corridor. The reason is fairly simple: The Turkish military would not launch such a bold initiative without the active backing of the United States, if not NATO as a whole. It’s not that Turkey can’t do it: In 1998, it successfully intimidated the Syrian regime simply by massing its large army on the border.

But this crisis has exposed the weaknesses in Erdogan’s regional ambitions. As a former imperial power under the Ottomans, Turkey cannot intervene in an Arab state without risking a broad backlash. Its mildly Islamist Sunni government raises suspicions among Syria’s large Christian and Kurdish minorities — not to mention Assad’s Alawites.

But this crisis has exposed the weaknesses in Erdogan’s regional ambitions. As a former imperial power under the Ottomans, Turkey cannot intervene in an Arab state without risking a broad backlash. Its mildly Islamist Sunni government raises suspicions among Syria’s large Christian and Kurdish minorities — not to mention Assad’s Alawites.

Sectarian tensions have also undermined the Arab League’s effort to assert itself. Sunni states, such as Saudi Arabia and Qatar, that have been eager to intervene have been checked by Shiite governments in Iraq and Lebanon. Meanwhile, independent efforts by the Gulf states to provide arms to the opposition have floundered.

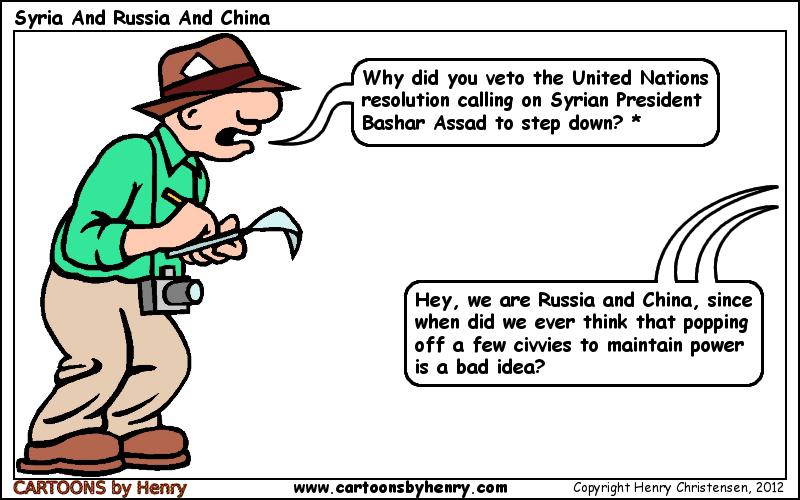

As for Russia, its bid to reestablish itself as a player in the Middle East by brokering a Syrian settlement is also failing.

As for Russia, its bid to reestablish itself as a player in the Middle East by brokering a Syrian settlement is also failing. The Kremlin wants to save Assad, but he refuses to take even the modest steps needed to open the way for a regime-preserving deal. Moscow can prevent the Security Council from authorizing tougher sanctions or military intervention, and it can supply the Syrian army with weapons and fuel. But the past few weeks have shown that it can’t stop Syria’s slide into civil war.

That leaves the U.N. mission of Kofi Annan, who appears determined to repeat every mistake the United Nations made in the Balkans when he was secretary general during the 1990s. He has persuaded the Security Council to send unarmed monitors to observe a cease-fire, when fire has not ceased; he has responded to lies and broken promises from Assad by renewing rather than abandoning his mediation.

A gloomy defeatism has infected European and Arab diplomats working on Syria. They shrug and say there are no solutions, that not much can be done to stop the fighting and that there’s no way to build an international consensus for stronger measures.

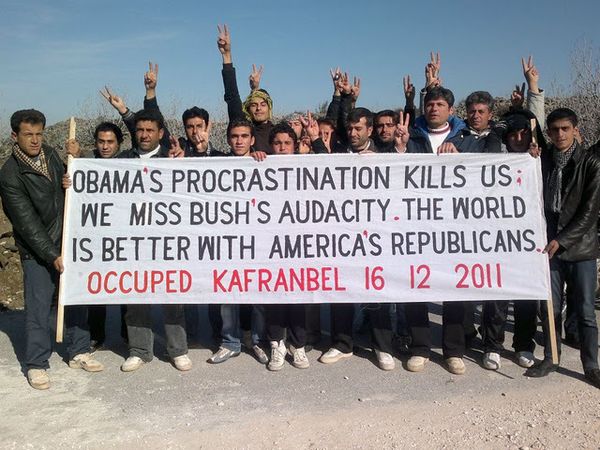

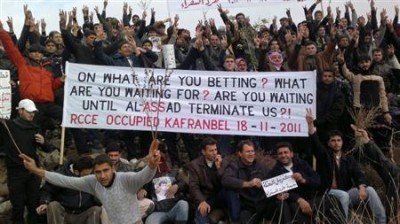

They say that — and then they speculate about when and whether the Obama administration might decide to abandon its passivity. The United States, after all, is more than capable of creating and defending a humanitarian zone in Syria, with help from Turkey and NATO. If it were to support the arming of the Free Syrian Army, there is little question that the army would soon have more weapons. Many in the Syrian opposition believe that merely the announcement of such U.S. initiatives would cause Assad’s regime to crumble from within.

What’s missing, of course, is a decision by President Obama to make that commitment. To do so, he would have to set aside the idea that any action must be authorized by the U.N. Security Council

What’s missing, of course, is a decision by President Obama to make that commitment. To do so, he would have to set aside the idea that any action must be authorized by the U.N. Security Council. He would have to forge an ad hoc coalition with Turkey and other NATO members, led by the United States. And he would have to order U.S. diplomats to work intensively with Syria’s opposition movements and ethnic communities to build an accord on a post-Assad order.

In other words, Obama would have to behave as if the United States were still what Bill Clinton understood it to be: the indispensable nation.

Washington Post

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.