By Hesham Shawish

When Randa Makhoul, an art teacher at a school in Beirut, asks her students a question in Arabic, she often gets a reply in English or French.

“It’s frustrating to see young people who want to speak their mother tongue articulately, but cannot string a sentence together properly,” she said at the Notre Dame de Jamhour school in the Lebanese capital.

Mrs Makhoul is just one of several Lebanese teachers and parents who are concerned that increasing numbers of young people can no longer speak Arabic well, despite being born and raised in the Middle Eastern country.

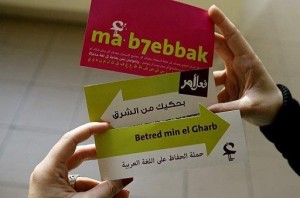

She welcomes a government campaign to preserve Arabic in Lebanon, called “You speak from the East, and he replies from the West”.

“This campaign aims to raise awareness about the importance of protecting Lebanon’s official language,” says Amal Mansour, media spokeswoman at the Lebanese ministry of culture.

“We encourage the learning of foreign languages, but not at the expense of the country’s mother tongue.”

Polyglot country

Arabic is the official language of Lebanon, but English and French are widely used.

A growing number of parents send their children to French lycees or British and American curriculum schools, hoping this will one day help them find work and secure a better future.

Some even speak to their children in French or English in the home.

“It’s sad no-one in our generation is speaking Arabic properly anymore,” says Lara Traad, a 16-year-old student at Notre Dame de Jamhour, one of Lebanon’s many French curriculum schools.

“I really regret that my parents did not concentrate more on developing my Arabic. It’s too late now, but maybe for the younger students in the country something can be done.”

Even with Arabic, there is a big difference between the classical, written form of the language and the colloquial spoken Lebanese dialect.

The classical language is almost never used in conversation – it’s only heard on the news, in official speeches, and some television programmes.

As a result, many young Lebanese struggle with basic Arabic reading and writing skills, and it is not uncommon for students as old as 16 or 17 to speak only broken Arabic.

Wider problem

The problem is seen in several parts of the Arab world where foreign schools are common – the UAE, Jordan, Egypt and most North African states.

Citing the wide gap between the formal language and its various colloquial forms within the Arab world, Egyptian philosopher Mustapha Safwaan once wrote that classical Arabic was theoretically a dead language, much like Latin or ancient Greek.

But language expert Professor Mohamed Said says classical Arabic is a unifying force in the Arab world.

“Classical Arabic is the language of communication, literature, science, philosophy, the arts – it is something that unites the Arab world,” says Prof Said, a senior Arabic language lecturer at London’s School of Oriental and African Studies.

According to Prof Said, colloquial dialects in the Arab world should not be seen as separate linguistic entities, but a continuance of the classical Arabic form.

Lebanon’s language campaign is the first of its kind to be launched by an Arab government.

The culture ministry organises talks in schools to raise awareness among pupils about the importance of protecting their mother tongue, and encouraging them to take pride in it.

Mrs Mansour, the ministry spokeswoman, says the government hopes that protecting the Arabic language in Lebanon will in turn protect the country’s identity and heritage.

Whether the initiative is enough to change how Lebanon’s youth communicate and express themselves is another matter. BBC

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.