By Jake Dizard

For the last four years running, Freedom House’s annual evaluation of political rights and civil liberties, “Freedom in the World,” has identified a worrisome global deterioration. The newly released findings of a more detailed analysis of democratic governance, “Countries at the Crossroads,” affirms the troubling trends in quality of institutions and depth of citizen freedoms across a set of selected states occupying the world’s political “middle ground.”

The problems seen in various regions afflict the Middle East with particular strength. In all Freedom House analyses, Middle Eastern states consistently receive the lowest scores of any region. The lack of free and fair elections in the region is certainly a primary factor, but broader institutional deficits, the opacity of policymaking, the lack of accountability for human rights violations, and the prevalence of both de facto and de jure religious and ethnic discrimination all factor into the generally poor performance.

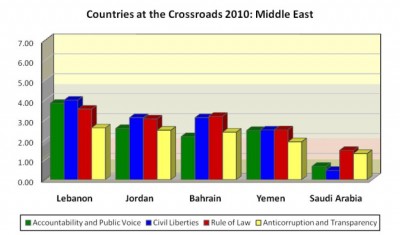

Crossroads derives its findings on the state of democratic governance from 75 separate questions arranged in 17 subcategories and four core categories: accountability and public voice, civil liberties, rule of law, and anticorruption and transparency. The Middle Eastern states included in the 2010 edition — Bahrain, Jordan, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, and Yemen –demonstrate a range of strengths and weaknesses regarding institutional quality and respect for basic freedoms, but generally lag behind their counterparts elsewhere. More troublingly, the findings for the three states with previous data reveal a largely negative trajectory over the coverage period of December, 2005 to June, 2009.

Two of the states, Saudi Arabia and Lebanon, were included in the survey for the first time and occupied the upper and lower bounds of regional performance, respectively. Lebanon’s unique political system allows participation by a variety of faiths and ethnicities, but its rigidity limits the prospects for progress in critical areas, including judicial reform and anticorruption efforts. Saudi Arabia, while demonstrating a faint, incipient reform impulse, remains a religion-based autocracy in which citizen rights are tightly circumscribed in nearly all areas.

Bahrain, Jordan, and Yemen can be compared to previous findings compiled in 2006, and developments were not encouraging. Jordan, which at one time was viewed as possessing one of the region’s more promising environments for governance reforms, largely stagnated while backsliding in key areas. Score setbacks were related to greater government interference in the 2007 elections than in past polls, new legal constraints on civil society activity, and increased revocation of citizenship of Palestinians of West Bank origin. While the anticorruption and transparency score rose slightly as a result of passage of new freedom of information law, the general maintenance of power within an insular elite class has overall staved off meaningful political liberalization.

Bahrain and Yemen, on the other hand, registered some of the most significant drops of the 32 countries in the edition. In fractious, conflict-plagued Yemen, the authorities used arbitrary and abusive methods to counteract civil unrest even as President Ali Abdullah Saleh’s determination to retain power hardened. Performance declined in each of the four main categories, with civil liberties especially hard hit due to violations by the security forces and increasing limitations on religious practice. In Bahrain, where a Sunni minority rules over a Shiite majority, heightened tensions and violence against political activists led to declines in citizen protection from state terror, freedom of association, and religious freedom, among other topics. The space for free expression also declined as the government increased already tight restrictions on accessing online information and detained several bloggers.

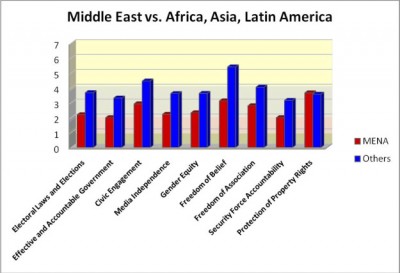

Within the region as a whole, opacity within narrow elite classes is common, leading to particularly low scores for the anticorruption environment. Middle Eastern states consistently lag behind those in other regions in a variety of the Crossroads subcategories, including minority rights, women’s rights, and accountable government. In addition, the country narratives portray a notably broad range of tactics used by government agents to suppress basic freedoms, ranging from legal harassment to physical attacks to the use of patronage networks to ensure the political loyalty of individuals at key institutions. The only subcategories in which the regional average score rises to a mediocre 3.0 out of a maximum 7 points are property rights and freedom of religion. The difference between this set of Middle Eastern states and the rest of the countries in the survey is starkly revealed by the chart below:

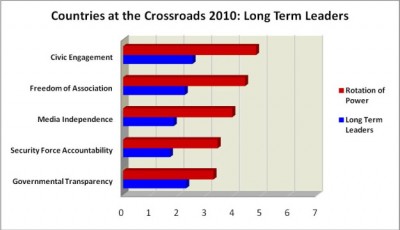

Another notable finding in the survey is that democratic freedoms are particularly under stress in a group of eight countries examined in this cycle of Crossroads: Bahrain, Cambodia, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Uganda, Vietnam, Yemen, and Zimbabwe. These states — four of which are in the Middle East — have sidestepped an elemental aspect of democratic governance: the rotation of power. Their political systems are not open to the rise and fall of competing political parties and groupings, and no interchange of government and opposition has occurred in at least the past 10 years. Instead, power is retained indefinitely by an individual or through the managed transfer of power within families or party hierarchies.

An examination of Crossroads scores reveals a significant difference between these eight states and the rest of the country set with respect to citizen participation in politics, including civic engagement, free expression, and free association. These rights, when effectively harnessed, can convert diffuse political sentiments into organized political movements. Ruling elites in long-term leader countries clearly have a narrow interest in preventing such movements. However, the associated politicization and dysfunction of what should be independent “referee” institutions — the judiciary, electoral commissions, prosecutorial services, and ombudsman agencies, among others — leads to routine injustice. The rulers may keep their grip on the state, but an increasingly frustrated public is left with no legal means of airing or addressing their grievances. In the Middle East, of course, such frustrations are also often associated with the spread of politico-religious violence.

Middle Eastern leaders are not immune to concerns about their image, of course. Indeed, several of the states in the region go to significant lengths to assure international donors that reform efforts remain underway. However, like many other countries analyzed in Crossroads, these efforts tend more often to take the form of legal reforms that appear impressive on paper but are implemented only partially or sporadically. This combination of incomplete reform and outright regression poses a challenge to international policymakers, including those within the U.S. government and at the World Bank and the Millennium Challenge Corporation, who have sought to create inducements for developing countries to improve democratic accountability. Rejuvenated efforts to give democratic rights issues a prominent role in dialogue with regional leaders — and to be explicit about concern over reform backsliding that results in lower citizen voice and increased rights violations — is critical in working to assure that the recent setbacks can be reversed. Foreign Policy

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.