By Liz Sly

AL-QASR, Lebanon — That half of his farm lies in Syria and half in Lebanon is a source of mystery and inconvenience for Mohammed al-Jamal, whose family owned the property long before Europeans turned up and drew the lines that created the borders of the modern Middle East.

Jamal has mostly ignored the invisible frontier that runs a few yards from his house — and so did the Syrian civil war when it erupted nearby. Relatives were kidnapped, neighbors volunteered to fight and shells came crashing in, killing some of his cows, injuring three workers and underlining just how meaningless the border is.

“I blame Sykes-Picot for all of it,” said Jamal, referring to the secret 1916 accord between Britain and France to divide up the remnants of the collapsing Ottoman Empire. The result was the creation of nation-states where none had existed before, cutting across family and community ties and laying the foundations for much of the instability that plagues the region to this day.

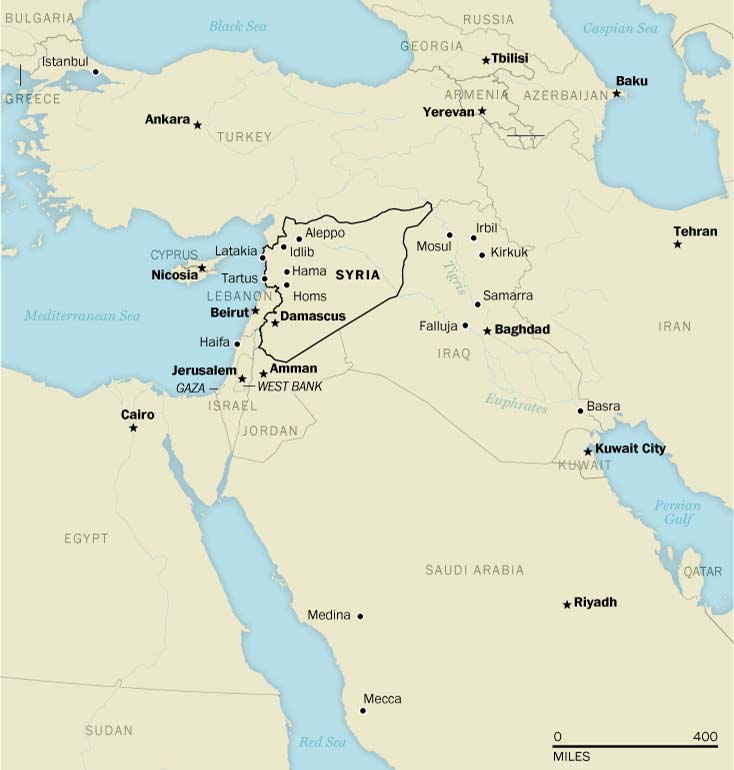

Less than a century after they were drawn, the durability of those borders — and the nations they formed — is being tested as never before. The war in Syria is spilling into Iraq, Lebanon, Turkey, Jordan and Israel, sucking in places that for centuries belonged to a single entity and people whose history, faith and livelihoods transcend the nations in which they were born.

Sunnis from across the region are pouring into Syria to fight alongside the rebels, many in pursuit of extremist ideals aimed at restoring Sunni dominion. Shiites from the same countries are flocking to defend President Bashar al-Assad’s Shiite-affiliated regime, compounding the sectarian dimension of a war that no longer is just about Syria.

Civilians are fleeing in the opposite direction, 2.3 million of them to date, transforming communities lying outside Syria in ways that may be irreversible.

“From Iran to Lebanon, there are no borders anymore,” said Walid Jumblatt, the leader of Lebanon’s minority Druze community. “Officially, they are still there, but will they be a few years from now? If there is more dislocation, the whole of the Middle East will crumble.”

Nobody seriously expects existing borders to be formally redrawn as a result of the ongoing upheaval. But as world powers prepare to gather in Switzerland next month for talks aimed at ending the Syrian conflict, this is a moment every bit as profound as the one that followed World War I when the region’s nations were born, said Fawaz Gerges of the London School of Economics.

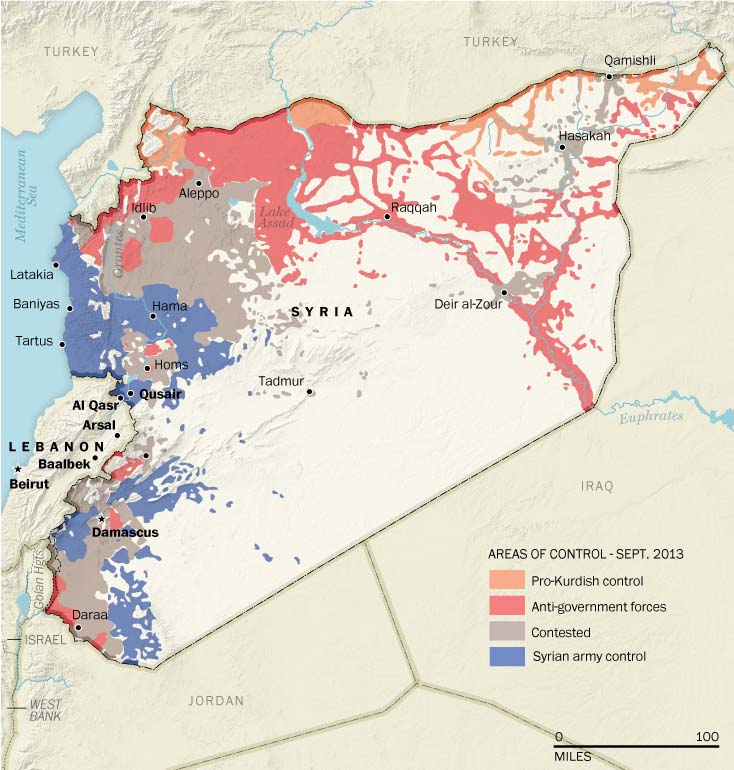

Already the chaos of Syria’s civil war has muddled the map, creating new frontiers that more closely coincide with the communities they contain. Four flags now fly over the territory known as Syria, representing the competing visions of sect, identity and allegiance that the war has exposed — and the pieces into which it might break.

The outcome could be further fragmentation of the existing states, or perhaps a longer-term consolidation that blurs the borders dividing them, Gerges said.

“Everything is in question now, and it is all very difficult to predict,” he said. “But what we are realizing is that the Middle East state system set up after World War I is coming apart.”

‘Sectarian borders are real’

The Middle East that eventually emerged from World War I bore little resemblance to the one laid out in the Sykes-Picot agreement, named for the British and French diplomats who bisected the region from east to west at a meeting in London.

But the line-drawing endeavor set the tone for the exercise in nation-making that came next. To this day, it is Sykes-Picot that is recalled and condemned by those living in the shadow of its consequences.

Plans for an independent Arab homeland were dropped. Instead, the British assumed full control over the territory corresponding to Iraq, Jordan, Palestine and later Israel. The French took Syria and carved from it Lebanon as a sanctuary for Christians, a loss that Syria has never formally accepted.

One of the borders they drew cut through al-Qasr, among numerous small farming villages dotting the lush fertile land fed by the streams of Mount Hermel in the remote northeastern corner of Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley.

The overwhelmingly Shiite community proclaims its allegiances with portraits of Syria’s Assad and Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, strung alongside those of the only Lebanese figure featured — Hasan Nasrallah, leader of the Hezbollah militant group. Shop windows are plastered with photographs of the men of the village who have died fighting in Syria for Hezbollah, whose contribution has proved key to a string of recent victories by Assad’s government.

“We never had borders between us. We consider ourselves one territory,” said Mohammed Shamas, 22, whose shop adjoins the border. “But a long time ago, the French came and drew these lines.”

More real for the residents here is the unmarked boundary that divides the Shiite villages in the foothills of Mount Hermel from the closest Sunni town, Arsal, which has been transformed by the revolt in Syria into a hub for the opposition. Tucked high in stony mountains 25 miles away, its streets teem with Syrian refugees, Syrian rebels, ambulances ferrying wounded Syrian fighters from the front lines and taxis plying the route to the nearest Syrian town, Yabroud.

Few people here travel the opposite direction, toward Lebanese towns, fearful after a spate of abductions and killings between the Lebanese Shiite and Sunni communities fueled in part by the Syrian war.

“We consider this place more Syrian than Lebanese,” said Abu Omar, an Arsal resident who runs a small clinic helping wounded fighters and did not want his real name to be used because he fears trouble from Lebanese authorities over his activities. He takes his family shopping to rebel-held Yabroud, notwithstanding shelling and airstrikes, because he would not dare move deeper into Lebanon. “The sectarian borders are real,” he said.

Jamal, the Shiite farmer whose property straddles the Syrian border, does all of his shopping in the Syrian town of Homs, not because he fears the journey to other Shiite towns but because Homs is cheaper and more convenient. “I would never go to Arsal. There they are all takfiris,” he said, referring to Sunni extremists.

“They made sure when those borders were drawn to maintain trouble between us forever,” he added. “It was on purpose.”

Reshaping the map

Similar undrawn boundaries are starting to take shape all over the region as the civil war enters its third year.

In the desert lands between the Euphrates and Tigris rivers — the Mesopotamia of ancient history — the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria is extending its reach into Syria and Iraq, flying the al-

Qaeda flag on both sides of the border. Its aim of restoring the Sunni Muslim caliphate has drawn Sunni volunteers from across the region.

In Syria’s far northeast, Kurds have declared autonomy in areas, raising the Kurdish flag and stirring hopes of independence for a community that lost out when the post-World War I map was made.

Assad loyalists, bolstered by the influx of Shiite volunteers from Lebanon and Iraq, are consolidating their hold on a spine of territory stretching from Damascus, the capital, to the coast, where most of the Shiite-

affiliated Alawite minority lives, sustaining the reach of the two-starred Syrian flag of the four-

decade-old Baathist regime.

In each location, massacres and persecutions of sects that find themselves on the wrong side of the lines are corroding the diversity that historically characterized Syria. Christians and Alawites are fleeing rebel-held areas, Sunnis who sympathize with the rebels are escaping government-controlled ones, swarming into Lebanon, Turkey, Jordan and Iraq with little indication that they will be able to go home anytime soon.

And over each dominion, foreign powers hold sway, sponsoring their proteges with money and weapons to further their own advantage. Saudi Arabia, Qatar and other states of the Persian Gulf back the Islamist rebels; Iran and Russia support the government, echoing the big-power rivalry that shaped the map a century ago.

The United States and Europe stand behind the fourth flag flying over Syria, the three-starred one adopted by the original, more-moderate proponents of the revolt, who sought to replace Assad’s dictatorship with a democracy. But without much in the way of funding or arms, theirs is the flag whose space is shrinking the fastest.

What is the solution?

Yet partition, which is where the dislocation inevitably seems to be heading, is an outcome that few people say they are willing to countenance, aside from the Kurds, who have long coveted a state of their own.

Although rulers have failed to translate nation-states into viable entities, most people have embraced the identities of the countries in which they live, said Malik Abdeh, a Syrian opposition writer based in London.

“It is the failure of political elites to offer any kind of vision that transcends sects that sustains sectarianism,” he said. “Notions of the nation-state are still very strong, even if the reality doesn’t correlate with prevailing ideals.”

Even the war’s brutality speaks to the intent of all the factions to win the conflict outright, with government forces routinely bombarding the rebel-held areas of the north from which their troops were ejected long ago, and rebels sustaining their pressure on Damascus with new offensives.

At a Hezbollah office in Hermel, the Shiite town that administers al-Qasr, an official who spoke on the condition of anonymity because he is not authorized to talk to the news media denounced the fragmenting landscape as an American plot to split the Arab world into weak, divided statelets to affirm Israel as the region’s most powerful country.

It is not what he or other Shiites want.

“If sectarian enclaves were allowed to happen, Christians would be a minority; Shiites and Alawites would be a minority in a sea of Sunnis,” the official said.

Sunnis suspect a similar plot but blame the British, a throwback to the betrayal of their hopes for independence after British army officer T.E. Lawrence, a.k.a. Lawrence of Arabia, helped lead the Arab revolt against the Turks. They, too, fear the consequences of a new divide that would confine them to the region’s desert heart.

“If Syria is partitioned, there will be war for 100 years to come,” said Abu Zeid, 37, a Syrian refugee from Damascus who runs a restaurant in Arsal. “The Alawites will have the coast, the Kurds will have the oil, and the Sunnis will be in the middle with nothing. The only solution is to share everything.”

The challenge in the Geneva peace talks between the Syrian opposition and the regime will be to produce an agreement on a new form of governance that will end the fighting. If it fails, further fragmentation seems inevitable, said Hilal Khashan, a professor of political science at the American University of Beirut.

Over time, however, greater decentralization, in which local communities have more say over their affairs, may produce fairer and more stable societies, he said, describing “a sort of umbrella of nations where different groups enjoy their own culture and way of life.”

For the region’s borders to disappear “would be like utopia,” said Issam Bleibeh, the deputy mayor of Hermel, as he sat mulling ways the war might end with a group of friends at his home in the little town, whose streets, like those of nearby al-Qasr, are lined with photographs of the dead.

They failed to think of one.

“The wars will change, but there will always be wars,” Bleibeh said. “One day it could be Muslim-Christian, then Shiite-Sunni, then Sunni-Sunni. The only certainty is that there will always be wars.”

First published in the Washington Post

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.