As Syria’s agony deepens, and once more the talk is of using western military force to stem the tide of misery, Guardian’s Middle East editor considers scenarios for the stricken country.

As Syria’s agony deepens, and once more the talk is of using western military force to stem the tide of misery, Guardian’s Middle East editor considers scenarios for the stricken country.

A NEGOTIATED EASING

Problem

All stakeholders recognise that the disintegration of Syria is a threat to their own interests and now has a self-sustaining momentum that is bigger than their capacity to control. In recent months, many players have made a series of small, unilateral gestures. The aim has been to build trust and to draw each other back from maximalist positions which have meant that all of those involved in Syria parties have treated it as one big fire sale, taking whatever they can from the ruins, before they’re picked clean.

Evidence

The moves have been small, but symbolic: an accused Saudi terrorist was picked up in Beirut, then flown to Riyadh after hiding out with Iran’s help for 20 years; Russia agreed to a UN probe to ascertain responsibility for the sarin massacre in Damascus; the Russians went to Riyadh, then the Saudis reciprocated with a trip to Moscow; low-level summits in Oman and Doha; the first Qatari ambassador to Baghdad in 25 years. The trust-building measures are gaining impetus, but they haven’t yet got Russia, Turkey, the US, Saudi Arabia or Iran anywhere near the grand bargaining table. The overriding issue is now bigger than Syria, with the very future of Iraq, Lebanon, Turkey’s southern border, the Kurds and minorities across the region now at stake.

Likelihood

An easing is likely to continue, but without bold bilateral moves – which at this stage remain unlikely – diplomacy seems set for more of a sideline role.

Problem

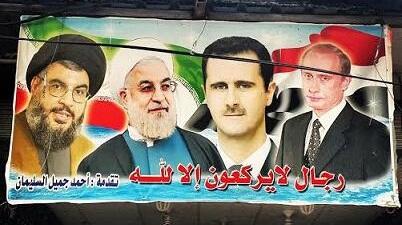

The Achilles’ heel of diplomacy is that the ambitions of the stakeholders in Syria remain fundamentally at odds with each other. Iran will not compromise on its core goal of ensuring that Damascus remains a strategic bridgehead for Hezbollah, its proxy militia, which remains a potent threat to Israel’s northern border. And Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the Gulf Cooperation Council will not give way on their insistence that President Bashar al-Assad has been the key driver of Syria’s collapse, the mass exodus of its people and the raging insurgency.

Evidence

Privately, Iranian officials have told rival diplomats that they are not wedded to Assad. However, in order for the Syrian capital to remain a reliable conduit for supplies to Hezbollah and Iran’s special interests elsewhere in the region, it needs to retain the systems and structures of the current regime, which means having personnel in place who can be trusted to make things happen. That means the Old Guard, the very people who have driven the war from the regime side and who the backers of the opposition insist on being removed.

Likelihood

A compromise here seems hard to come by, which doesn’t augur well for an end to the fighting any time soon. In the meantime, Assad now controls less than 25% of Syria, a strip running north-west from the Golan Heights, through Damascus, Homs, Hama (the heartland of his Alawite sect), then to Latakia, and Tartous on the coast. The rest of Syria is in the hands of various arms of the opposition and of jihadis, such as Isis, and is well beyond his capacity to win back. The default to the residual rump of the country, “the Syria that matters”, is the most likely scenario in the short to medium term, with eastern Syria and western Iraq remaining well outside the control of both those crumbling states.

FULL MILITARY INTERVENTION

Problem

Evidence

Despite occasional rhetoric, there remains no appetite in Washington, London, Ankara or Paris for a western intervention to topple Assad amid the chaos. The United States in particular remains very wary about being drawn back into a region that it had vowed to leave less than four years ago and, in the face of repeated failings, is sticking to its model of trying to act in support of states such as Iraq, rather than leading the fight on its behalf.

Likelihood

US jets have been flying in Syrian skies to bomb Isis for more than a year. Turkey has sent its own jets in the past month, but they have primarily targeted the Kurds, instead of the jihadis. Isis is, for now, the quarry, and this is unlikely to change unless there is substantial progress on the diplomatic front. Only then would the appetite for military muscle – in support of diplomatic aims – possibly increase.

THE GUARDIAN

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.