The three men, wearing white prison scrubs in metal cages reserved for criminal suspects, listened to the list of explosive charges accusing them of aiding a plot to undermine Egypt’s national security.

The three men, wearing white prison scrubs in metal cages reserved for criminal suspects, listened to the list of explosive charges accusing them of aiding a plot to undermine Egypt’s national security.

They had links to terrorists, the prosecutors contended, and before their court appearance on Thursday, the men were detained for weeks among prisoners whom the government considers its most dangerous opponents. The charges could bring up to 15 years in prison.

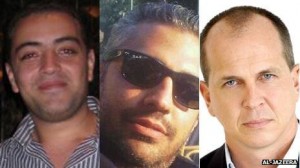

But the three suspects are all seasoned journalists. Their crime was filing news reports for their employer, Al Jazeera English, before state security officers came to the hotel suite they used as a makeshift studio in December, ultimately rounding them up and throwing them in jail.

The charges against the men, branded the “the Marriott cell” by government-friendly news outlets, are the most serious against journalists here in recent memory, rights groups say, part of a widening crackdown by Egypt’s military-backed government that has ensnared scores of reporters, as well as filmmakers, bloggers and academics.

What began months ago with mass arrests and repression of the government’s opponents in the Muslim Brotherhood has steadily broadened into a campaign against perceived critics of all stripes. In all, thousands of people — mostly Islamists, but also some of the best-known activists from the uprising that toppled President Hosni Mubarak — have been put in jail, many of them still awaiting trial.

At least 60 journalists have been detained since the military ousted President Mohamed Morsi last July, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists, with nine of them still in custody, including a Yemeni blogger arrested after interviewing attendees at a book fair.

“This is a dangerous decision,” Peter Greste, one of the journalists from Al Jazeera English, wrote about his arrest in a letter from prison. “It validates an attack not just on me and my two colleagues, but on freedom of speech across Egypt.”

Beyond Mr. Greste and his two colleagues from Al Jazeera English — Mohamed Fadel Fahmy and Baher Mohamed — 17 other people are charged in the same case, including several students who appeared in court on Thursday as well. The allegations include possessing materials promoting a terrorist organization — presumably, the banned Brotherhood — and broadcasting images that the government says distorted Egypt’s image by suggesting that “the country is undergoing a civil war.”

The trial reflects a particularly intense struggle between the Egyptian government and Qatar, which owns Al Jazeera. Egypt accuses Qatar of harboring Islamist leaders, including wanted men, and complains that the channel provides a platform for Egypt’s enemies.

The network’s Arabic language news service, like the Qatari government, strongly supports the Brotherhood, the Islamist group that had become Egypt’s governing party until the military takeover last summer. Afterward, Egyptian officials shuttered the station’s news bureaus and detained reporters and staff members. One of its journalists, Abdullah Elshamy, has been imprisoned since August and is on a hunger strike.

Journalists with the English-language service, which takes an independent editorial line, have continued to work in Egypt. When Mr. Fahmy joined the network just last September, he assured his family that the English channel was looked upon more favorably in Egypt.

Mr. Fahmy, an Egyptian and Canadian citizen, has worked for the some of the world’s biggest news organizations, including CNN, The Los Angeles Times and The New York Times, and was an author of a book on the uprising in his Egyptian homeland. The job at Al Jazeera English made him a bureau chief for the first time, and provided a dose of stability as he was preparing to get married after years of bouncing around on assignments, often in war zones like Iraq and Libya.

His co-defendant Mr. Mohamed comes from a family of Egyptian journalists and had worked as a freelance producer for Al Jazeera for about seven months, his brother Assem said. Mr. Greste, an Australian correspondent who had worked for the BBC and Reuters, did not even live in Egypt. He was based in Nairobi, Kenya, and had been filling in over the Christmas holiday in Cairo when security officers came for him and his colleagues.

A video leaked to an Egyptian news channel after their arrest showed security officers interrogating Mr. Fahmy and Mr. Greste, who both looked bewildered. Mr. Mohamed was arrested later that night. During the raid on his house, officers shot Gatsby, the family dog, his brother said.

When pressed about their handling of the news media, some Egyptian officials said it was not so different from the Obama administration’s crackdown on leakers in national security cases. And in Al Jazeera English’s case, they have repeatedly emphasized that the men were working without press credentials in Egypt, a point their employer has conceded.

“We were wrong,” said Heather Allan, the head of news gathering for the channel, who attended the trial on Thursday. But officials had also told her that the channel was not banned, she said. “We were not operating clandestinely,” she added.

The official explanations shed little light on why a Dutch journalist who did not work for Al Jazeera was named as a suspect in the case, and forced to flee Egypt: Her crime, it appeared, was meeting with Mr. Fahmy. And the relatively simple matter of credentials did not seem to explain the treatment the Al Jazeera English journalists received after their arrests, which they detailed in harrowing letters and messages from prison.

In the first weeks, Mr. Greste was treated the most kindly, allowed an exercise session after being “locked in my cell 24 hours a day for the past 10 days, allowed out only for visits to the prosecutor for questioning.”

Around him, at Tora prison in Cairo, “authorities routinely violate legally enshrined prisoners’ rights, denying visits from lawyers, keeping cells locked 20 hours a day,” he wrote. “But even that is relatively benign compared to the conditions my colleagues are being held in.”

Mr. Fahmy and Mr. Mohamed were sent to a wing known as Scorpion, where their neighbors were Islamist political detainees and hardened jihadists.

In a message to his family, Mr. Fahmy described a cell “infested with insects, freezing cold, with access to little food and no sunlight at all.” Privileges — like a blanket — were granted and then snatched away. An arm broken before his arrest was left untreated and grew worse, he said.

He and Mr. Mohamed relied on work to preserve their sanity, hosting evening discussions with other prisoners through the grates of their cells. They called it the “Scorpion Live Talk Show.”

The three colleagues were eventually moved together to a less secure wing, and placed in the same cell, with improved conditions. In court on Thursday, they appeared buoyed by the attendance of more than two dozen diplomats and journalists.

Mr. Fahmy translated the proceedings, which were in Arabic, for Mr. Greste, who was not provided with an interpreter. During breaks, the journalists shouted answers to questions from their colleagues in the gallery, struggling to put on a brave face. They spent 23 hours a day in their shared cell, they said, with no access to news or reading materials. Their next court date is set for early March.

From the cage, they asked journalists to pass on greetings to absent relatives: to Mr. Greste’s parents, and Mr. Mohamed’s wife, who is pregnant and whom he begged to “take care.” Mr. Fahmy smiled and asked that word be sent to his fiancée, who was barred from the courtroom, to prepare for a “big wedding” when he got out.

NY Times

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.