The small electronics store a few blocks from Cairo’s Tahrir Square radiates light—a beacon in the darkness. At night, other shops in the turbulent area shutter, but owner Sameh El Sahihi insists on keeping El Kady Trade open late during what was once the prime shopping time in the sweltering Egyptian summer. On a recent night the streets were silent, his shop was empty, and Sahihi was furious. He had supported Mohamed Mursi’s bid for the presidency because he was sure the Muslim Brotherhood candidate would fix Egypt’s economy. “I thought he is religious, he has a good education … and he will rule the country fairly,” he says. “I was so hopeful after the elections that things would begin to change and I would be able to run my business well, but nothing happened.”

The small electronics store a few blocks from Cairo’s Tahrir Square radiates light—a beacon in the darkness. At night, other shops in the turbulent area shutter, but owner Sameh El Sahihi insists on keeping El Kady Trade open late during what was once the prime shopping time in the sweltering Egyptian summer. On a recent night the streets were silent, his shop was empty, and Sahihi was furious. He had supported Mohamed Mursi’s bid for the presidency because he was sure the Muslim Brotherhood candidate would fix Egypt’s economy. “I thought he is religious, he has a good education … and he will rule the country fairly,” he says. “I was so hopeful after the elections that things would begin to change and I would be able to run my business well, but nothing happened.”

Instead, things got worse. In October 2012, four months into Mursi’s term, the government floated a proposal to close shops at 10 p.m. to save on energy costs. “This provoked us because it would mean a huge income loss for anyone who has a business downtown,” Sahihi says. Inflation, petrol shortages, and blackouts made running a business even harder. “I want the economic wheel to keep turning. I don’t care about Shariah law; I’m just looking after my business,” he says. And so Mursi lost another supporter.

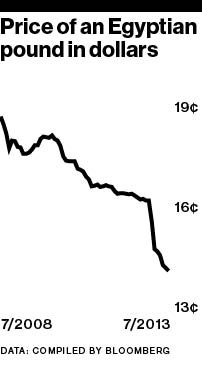

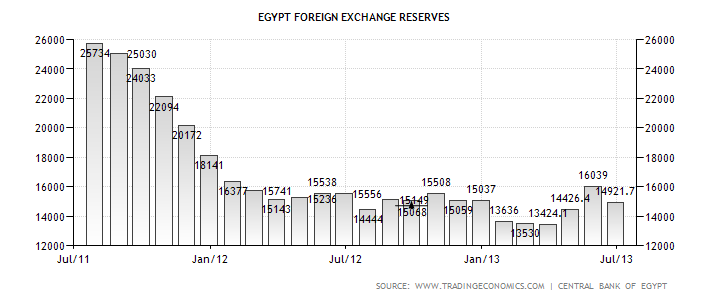

Since early 2011, Egypt’s economy has been one of the major grievances propelling the masses into the streets. Although the economic structure Mursi inherited was dysfunctional, for many his inability to stabilize the situation was the last straw. As foreign reserves dwindled, the currency dropped, inflation rose, and shortages spread, the government was nowhere to be found. Mursi was the one person visible enough to blame.

Ahmed el-Hawary, a founding member of the Dostour Party, which collected signatures in a campaign that called for the June 30 protest, says the economy was all anyone talked about in the weeks preceding the demonstrations. “The substantial part [of conversations] was not revolutionary rhetoric. The substantial part was people are barely able to feed themselves, with how the currency is devalued every day and all the groceries are getting more and more expensive,” el-Hawary says. Blackouts and water shortages in the early summer “made everybody feel they’re going to go into hunger and strife and won’t even have water to drink.” A steady supply of electricity “was one of the things we really enjoyed in Egypt for 30 years. We didn’t have blackouts, especially in the cities.” Collecting signatures against Mursi was a breeze.

Ahmed el-Hawary, a founding member of the Dostour Party, which collected signatures in a campaign that called for the June 30 protest, says the economy was all anyone talked about in the weeks preceding the demonstrations. “The substantial part [of conversations] was not revolutionary rhetoric. The substantial part was people are barely able to feed themselves, with how the currency is devalued every day and all the groceries are getting more and more expensive,” el-Hawary says. Blackouts and water shortages in the early summer “made everybody feel they’re going to go into hunger and strife and won’t even have water to drink.” A steady supply of electricity “was one of the things we really enjoyed in Egypt for 30 years. We didn’t have blackouts, especially in the cities.” Collecting signatures against Mursi was a breeze.

Under Hosni Mubarak, Egypt’s growth slowed but was still decent: The economy expanded 5.1 percent in 2010, his last year in office. That masked systemic problems. Although “there was investment, there was no trickle down at all. It was the kind of growth that increases inequality,” says Marina Ottaway, a senior scholar at the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington. In January 2010 the World Bank released a working paper that said infrastructure investment in Egypt had fallen sharply, especially in power generation and transportation, over the last 15 years.

As instability deepened, foreign investors fled. Since Mubarak stepped down in February 2011, foreign currency reserves have fallen to less than half of the $36 billion the old regime held. In May the budget deficit climbed to 11 percent of gross domestic product, up from 8.3 percent under Mubarak. Fitch Ratings predicts the economy is unlikely to expand more than 3 percent in 2014. That’s slow growth for a country where half the population is younger than 25 and headed for a labor market that can’t generate enough work. Official unemployment stands at 13.2 percent, though most agree it’s far higher. Since early 2010 more than 1 million people have lost their jobs.

Mursi’s government, like the interim military council before him, wavered on accepting a $4.8 billion International Monetary Fund loan. The IMF wants the government to phase out the $14.5 billion per year Egypt spends on fuel subsidies. Another $4 billion annually subsidizes food, mostly bread. Although the loan would restore investor confidence in Egypt, it’s deeply unpopular on the street and there are no guarantees the inefficient bureaucracy could cut subsidies without bringing even more people out to protest. To tackle this thorny issue, Mursi would have needed a broad political coalition. Instead, the Muslim Brotherhood’s inability to build a consensus isolated it. “These problems are too big for any one faction to deal with. All of them entail some level of social dislocation that requires wide political buy-in,” says Michael Wahid Hanna, senior fellow at the Century Foundation in New York.

In mid-2011, Egypt began to secure at least $10 billion in loans from Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Libya, and Turkey. Yet conditions worsened. El-Hawary, of the Dostour Party, realized Egypt was in dire straits in February, when its banks limited dollar withdrawals and transfers of U.S. dollars between accounts. From then on, prices on basic goods spiked as people hoarded gas, food, and dollars. By July, Mursi was out. Whether an army-backed interim government can solve any of Egypt’s economic problems is far from clear. “Where to start?” asks Hanna. “You have to start with the politics, and that’s even harder than it was before.”

The bottom line: Egypt’s foreign currency reserves are less than half the $36 billion the Mubarak regime had amassed.

Business Week

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.