BEIRUT , Lebanon – When clashes between Syrian rebels and government forces spilled into his Palestinian neighborhood outside Damascus, Amir knew where to go: Shatila, a teeming Palestinian camp in Lebanon notorious as the site of a massacre during Lebanon’s civil war.

BEIRUT , Lebanon – When clashes between Syrian rebels and government forces spilled into his Palestinian neighborhood outside Damascus, Amir knew where to go: Shatila, a teeming Palestinian camp in Lebanon notorious as the site of a massacre during Lebanon’s civil war.

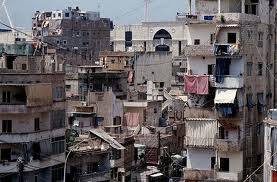

“Most of us have relatives here and friends in these camps, so we feel that they will break bread with us,” Amir said as he sat down for breakfast with friends in a cramped storefront in one of Shatila’s shadowed alleyways, winding between rows of concrete apartment blocks crammed with families.

Syria’s raging violence has forced more than 500,000 people to flee to neighboring nations, severely straining the capacities of Lebanon, Turkey and other host countries. The refugee crisis is the most dramatic illustration of how the Syrian conflict has been exporting instability.

For those displaced from Syria’s huge Palestinian community, the logical destination is often camps like Shatila, which offer relatively open access and a sense of solidarity among generations of residents who are part of the Palestinian diaspora that followed the 1948 creation of Israel.

The most recent arrivals are, in a sense, repeat refugees whose families have been uprooted in distinct episodes of Middle Eastern turmoil, separated by more than half a century. Though designated as camps, Shatila and other Palestinian enclaves are actually densely populated urban neighborhoods, desperately impoverished and dependent on aid from the United Nations and other donors.

“What the people of Syria are going through now is like what the Palestinians had suffered back in 1948, so they can understand our situation,” said Amir, a blue-eyed man in his 20s who, like many others interviewed here, declined to give his full name for security reasons.

Official numbers are hard to come by, but, according to camp administrators, Shatila’s population has almost doubled to 25,000 since the conflict in Syria ignited 20 months ago. The influx involves Palestinian Syrians and other Syrians, both drawn by the prospect of relatively inexpensive housing (if it is available) along with aid from relief agencies and from Shatila families who have opened their doors to the newcomers, though few here have much to spare.

On a recent afternoon, a group of Syrian women from the strife-torn southern province of Dara — where the Syrian rebellion began with street protests in March 2011 — was waiting to register at the camp office. Only a few of the women were Palestinian. All wore veils and some had their faces completely covered. They recounted how they had lost sons and husbands, nephews and grandchildren, dead, missing or imprisoned in the anarchy that has overtaken broad swaths of Syria.

On a recent afternoon, a group of Syrian women from the strife-torn southern province of Dara — where the Syrian rebellion began with street protests in March 2011 — was waiting to register at the camp office. Only a few of the women were Palestinian. All wore veils and some had their faces completely covered. They recounted how they had lost sons and husbands, nephews and grandchildren, dead, missing or imprisoned in the anarchy that has overtaken broad swaths of Syria.

“How can we live with a regime that has killed so many?” asked a matriarch named Rasmiyeh. Another woman said she had fled with her two daughters, ages 17 and 19, because of reports of armed men assaulting young women.

“I can take care of myself,” she said, “but I must protect my daughters.”

Even before the arrival of Syrian refugees, life in Shatila was challenging. There are few jobs, housing is scarce and residents live in a claustrophobic warren of alleys and narrow streets where the smell of raw sewage is sometimes overpowering. Winter rains turn the alleys into raging torrents; a tangled lattice-work of jerry-built wiring provides a cluttered canopy.

Still, there are none of the street battles and mortar barrages that battered Yarmouk, the sprawling Palestinian enclave outside Damascus that has become a battleground for supporters and opponents of the government of Syrian President Bashar Assad. Many Yarmouk residents, including Amir, relocated to Shatila.

The demands of an ever-expanding population have overwhelmed the Palestinian Authority, which runs Shatila.

“Look at the pharmacy!” Khaled Diab, who heads a camp clinic, lamented as he gestured toward a row of shelves bearing few supplies. “It’s virtually empty.”

Before the Syrian conflict, he said, the facility vaccinated about 15 children per month; that number has risen to 150. It is a similar story at the women’s health clinic, where a few patients each day have expanded to as many as 30.

Shatila, created in 1949 and covering less than a square mile on the southern fringes of the Lebanese capital, is both a vibrant hub of Palestinian culture and a marginalized outpost.

Posters of the late Yasser Arafat and other Palestinian leaders, dead and alive, are plastered on the oppressively gray walls. Construction crews busily add stories to buildings, vertical being the only way to expand when all other space is taken. Spray-painted graffiti exhorts the Palestinian cause — “My freedom is more precious than my life” — and commemorate the infamous massacre of 1982, when Christian Phalange forces allied with the Israeli military killed more than 800 residents in Shatila and another Palestinian camp, Sabra, both frequently targeted during the 1975-90 Lebanese civil war.

The camp’s bustling periphery is home to scrap metal and mechanic shops, some of the few places where Palestinians can find work. Lebanese law and union rules greatly restrict employment prospects, barring refugees from most good jobs, even if they are qualified. In Shatila, vendors push their carts along the uneven concrete, and scooters vie for space with pedestrians.

“The situation of a Palestinian living here is already very bad,” said Kazem Hassan, who administers the camp for the Palestinian Authority. “There are no work opportunities, no municipal services. And … there are not enough houses to cover people’s needs.”

Aid groups have been distributing cooking utensils as well as blankets for the coming winter. Children of Palestinian refugees from Syria have been granted access to schools run by the U.N.

But the U.N. and independent aid agencies working here agree that the need far exceeds what is available.

“Distribution of any assistance is dependent on the availability of funds,” said Hoda Samra Souaiby, spokeswoman for the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees, or UNRWA, which provides education, health and other social services to Shatila and dozens of other camps that are home to more than 5 million people.

Many here say they have received little or no aid from the U.N. or any other agency. Most newcomers appear to have moved in with other families.

“I need to rent a house, feed my three children. As a schoolteacher, I can’t find work,” said Um Mutaz, a Palestinian who spoke a few days after arriving from Syria and moving in with another family. “If I return [to Syria], even under the shells and the bombs, it is better. If I don’t find anything in the next two days, I’ll go back.”

A few days later, she did return, leaving relative safety in order to have a place of her own for her family to live.

LA Times

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.