Holding a microphone on a makeshift stage, Abdel Basset al-Sarout — former goalie of the Syrian national youth squad, current bard of the region’s bloodiest uprising — led a packed Homs street in a soul-stirring chant: “The people… want… military intervention!” In Homs, the evolution of chants has reflected the evolution of the opposition movement’s demands: from “the people want the fall of the governor,” to “the people want the fall of the regime,” to “the people want the execution of the president.” And, finally, to this.

Holding a microphone on a makeshift stage, Abdel Basset al-Sarout — former goalie of the Syrian national youth squad, current bard of the region’s bloodiest uprising — led a packed Homs street in a soul-stirring chant: “The people… want… military intervention!” In Homs, the evolution of chants has reflected the evolution of the opposition movement’s demands: from “the people want the fall of the governor,” to “the people want the fall of the regime,” to “the people want the execution of the president.” And, finally, to this.

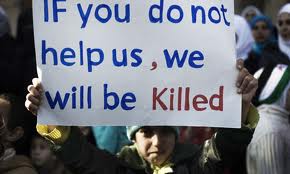

The chant would have been unimaginable not long ago. Fourteen months into their uprising and with no end in sight, Syria’s revolutionaries are in search of a game-changer. Revolution supporters have little faith in the Annan Plan and they retain few illusions that their movement’s current blend of popular protests and lightly-armed insurgency is sufficient to overthrow the regime. For months now, Syrian activists have debated whether international intervention is the silver bullet that could tip the balance of power in their favor. As the regime has continued its repression and as the poorly armed Free Syrian Army (FSA) has proven unable to protect the population, opinion among revolutionaries has shifted markedly — from little support for any type of foreign intervention during the spring of 2011 to widespread advocacy for some of the most aggressive options on the table.

Nowhere is this trend more evident than on the Facebook page from which calls for anti-government protests were first broadcast. The page, appropriately entitled “Syrian Revolution,” has become the established hub for Syrian activists online. It functions as both an influential media wing of the opposition (regional news outlets draw heavily from the page) and as a lively forum for debate among Syrian activists on the ground and abroad. The page has over 460,000 “likes,” far more than any other pro-Syrian revolution page on Facebook. Each day, page administrators post dozens of videos of protests and of government violence, as well as calls for coordinated action and opposition unity. These posts often receive hundreds of comments.

Nowhere is this trend more evident than on the Facebook page from which calls for anti-government protests were first broadcast. The page, appropriately entitled “Syrian Revolution,” has become the established hub for Syrian activists online. It functions as both an influential media wing of the opposition (regional news outlets draw heavily from the page) and as a lively forum for debate among Syrian activists on the ground and abroad. The page has over 460,000 “likes,” far more than any other pro-Syrian revolution page on Facebook. Each day, page administrators post dozens of videos of protests and of government violence, as well as calls for coordinated action and opposition unity. These posts often receive hundreds of comments.

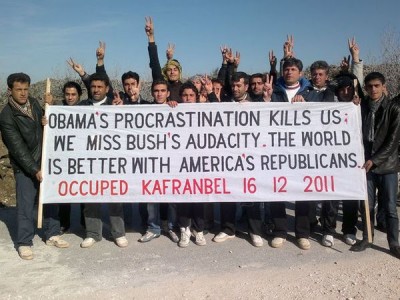

The page also plays a central role in the branding of the revolution — in determining the messaging that the opposition puts forward to the Syrian population, to the regime, and to an international audience. Syrian readers of the page, a diverse cross-section of the opposition, are asked to participate in weekly polls to choose the official title of each Friday’s protests (technically, non-Syrians can participate as well — and some do — but this is looked down upon). The winning title is then held up on placards and banners in demonstrations around the country, and is used as a point of reference in broadcasts on Al Jazeera and other Arab media outlets. While taking into account the self-selection bias that affects participation, the comments on the page and the results of the weekly votes to name the Friday protests provide an unscientific but still valuable window into how opinions about international intervention have evolved towards the extreme.

As the uprising spread during the spring and summer of 2011, discussion on the page suggested little support for direct foreign interference. Activists hoped that Syria would follow the Tunisian and Egyptian models of people-powered regime change. Yet when the much-anticipated Ramadan campaign of daily protests in August failed to undermine government control of Damascus and Aleppo, support began to build for foreign assistance. On September 9, 66 percent of nearly 20,000 voters in the weekly poll chose “Friday of International Protection” over seven other potential protest titles, alluding to a vaguely defined foreign intervention.

With violence against protesters escalating throughout the fall, 61 percent of more than 22,000 voters selected a clearer slogan for demonstrations held on October 28th: “No-Fly Zone Friday.” Five weeks later, a similar majority chose “Safe-Zone Friday,” a call to create internationally-protected areas within Syrian borders in which protesters and defected soldiers could safely organize. This Friday followed the “Friday of the Free Army Protects Me,” a title that pointed to the rising popularity of armed resistance. Activists made clear in comments on the page that they envisioned FSA operations, peaceful protests, and international intervention as complementary components of their push to overthrow the regime.

As the government’s crackdown intensified during the winter, calls for international support for the FSA grew more explicit and demands for foreign military action more extreme. A striking 86 percent of nearly 25,000 voters chose to name March 2 the “Friday of Arming the Free Army,” casting their votes as regime forces applied brutal force to wrest the Bab Amr neighborhood of Homs from opposition control. Two weeks later, shortly after pro-regime shabiha gangs had reportedly massacred dozens of women and children in Homs, 68 percent of roughly 21,000 voters chose to hold the Friday protests in the name of “Immediate Military Intervention.” A more cautious call for limited international action, “Secure Corridors Friday,” received less than 1 percent of the vote. For the majority of the page’s readers, the time for half-measures had passed. The Facebook banner advertising the March 16 demonstrations specified three types of “immediate” intervention: targeted airstrikes, and the establishment of no-fly and safe zones. Notably, the banner suggested that foreign military action should be carried out by “Arabs and Muslims before the West.”

Yet discussion on the page suggests that even explicit appeals for Western military intervention now enjoy increasing activist support. On March 5 and 6, page administrators published two posts asking readers if they support Senator John McCain’s call for airstrikes against the Assad regime. Taken together, the posts generated more than 600 comments. Leaving aside irrelevant comments, duplicates, and responses posted by readers whose profiles or dialects indicate that they are not Syrian, the trove of comments indicates rising support for Western intervention. Out of the 196 relevant comments scored, a strong majority of 64 percent supported McCain’s call for (presumably U.S.-led) airstrikes against regime military assets, while 23 percent opposed it. Thirteen percent addressed the topic but did not clearly define their preference. In a country where support for anti-American militants in Iraq once served as a point of pride, these appeals for Western military action are particularly jarring. Activists who posted in favor of airstrikes frequently voiced their support in terms of desperation, with many noting their suspicion of US intentions and doubt about McCain’s sincerity. As one self-proclaimed fan of prominent Syrian Salafi cleric Adnan al-Arour put it: “I wonder are they serious or is this empty talk to buy more time and kill more defenseless people? That being said, yes I support military strikes on this dog of a regime.”

While the issue of airstrikes remains somewhat contentious, arming the FSA does not. This represents a clear shift for a movement that initially rallied around slogans of non-violence. In the summer of 2011, commenters on the page often accused advocates of armed resistance of playing into the hands of the regime. Today, similar charges are directed at opposition politicians who reject arming the Free Army. Most of the leading activists — from on-the-ground organizers Khalid Abu Salah and Abdel Basset al-Sarout to competing exiled leaders Burhan Ghalioun and Haithem al-Maleh — demand international assistance for the outgunned rebels. At least five Fridays have been organized under a banner backing the military resistance, including the aforementioned March 2 call for arming the FSA. Chants in support of the FSA have also become common at rallies across the country, including at the massive February demonstrations in the upper-middle class Damascus neighborhood of Mezzeh.

While the issue of airstrikes remains somewhat contentious, arming the FSA does not. This represents a clear shift for a movement that initially rallied around slogans of non-violence. In the summer of 2011, commenters on the page often accused advocates of armed resistance of playing into the hands of the regime. Today, similar charges are directed at opposition politicians who reject arming the Free Army. Most of the leading activists — from on-the-ground organizers Khalid Abu Salah and Abdel Basset al-Sarout to competing exiled leaders Burhan Ghalioun and Haithem al-Maleh — demand international assistance for the outgunned rebels. At least five Fridays have been organized under a banner backing the military resistance, including the aforementioned March 2 call for arming the FSA. Chants in support of the FSA have also become common at rallies across the country, including at the massive February demonstrations in the upper-middle class Damascus neighborhood of Mezzeh.

Support for foreign intervention is not universal, of course. While the Syrian National Council and prominent activists have appealed for intervention, a vocal minority represented by the National Coordination Committee (NCC) rejects all forms of foreign military involvement, including arming the FSA. In opposing intervention, the leftists and Arab nationalists who dominate the NCC are joined by a smaller group of voices from far outside the opposition mainstream: Salafi-Jihadists sympathetic to al-Qaeda, who recognize that any type of Western aid in overthrowing the Assad regime will undermine their claim that only violent jihad offers Sunnis the means of overcoming Alawite oppression. Whether they are socialist or Salafist, however, vocal opponents of intervention are finding themselves increasingly on the defensive as conditions on the ground deteriorate. Indeed, it is common to see activists online charge the NCC and jihadist groups with the same unforgivable crime: collaboration with the mukhabarat, Syria’s hated internal intelligence services.

Regardless of the opposition’s wishes, it is far from clear that any type of foreign military involvement would save lives. This cannot be emphasized enough. Intervention could easily prolong the conflict and spark broader regional unrest. The potentially disastrous effect of sending thousands of small arms into Syria, for instance, is clear. Not only could it contribute to long-term instability, but it might also have regional consequences as weapons spilled over into neighboring countries like Jordan and Lebanon. Instituting a no-fly zone, and other uses of foreign air power, carry with them their own devastating human costs as well.

Failing to intervene, however, may further a trend that Western policymakers are loathe to accept: the radicalization of the opposition. Last week, as UN observers traversed the country, a massive car bomb targeted a military compound in Deir al-Zour. Such attacks have become increasingly common in the past few months. Ban Ki-moon and the Assad government have both been quick to blame Al Qaeda, while revolution supporters accuse the regime of staging such attacks themselves in order to hype the familiar terrorist boogeyman and tarnish the reputation of the opposition. Whoever may have carried out this latest bombing, there can be little doubt that Salafist factions — like Kataib Ahrar al-Sham, a lesser known militant group that has claimed responsibility for a series of roadside bombings on regime convoys–are playing an increasingly active role in the armed opposition. Thus, the troubling conundrum of international intervention: in the absence of (potentially counter-productive) foreign involvement, aggressive tactics — and the more radical ideologies associated with them — may gain broader appeal.

Failing to intervene, however, may further a trend that Western policymakers are loathe to accept: the radicalization of the opposition. Last week, as UN observers traversed the country, a massive car bomb targeted a military compound in Deir al-Zour. Such attacks have become increasingly common in the past few months. Ban Ki-moon and the Assad government have both been quick to blame Al Qaeda, while revolution supporters accuse the regime of staging such attacks themselves in order to hype the familiar terrorist boogeyman and tarnish the reputation of the opposition. Whoever may have carried out this latest bombing, there can be little doubt that Salafist factions — like Kataib Ahrar al-Sham, a lesser known militant group that has claimed responsibility for a series of roadside bombings on regime convoys–are playing an increasingly active role in the armed opposition. Thus, the troubling conundrum of international intervention: in the absence of (potentially counter-productive) foreign involvement, aggressive tactics — and the more radical ideologies associated with them — may gain broader appeal.

Huffington Post

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.