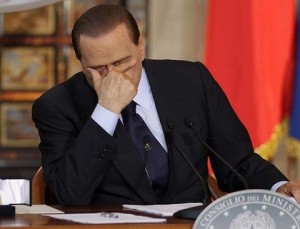

The European debt crisis threatened a second European government on Monday as the remnants of support for Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi of Italy seemed to be eroding rapidly in face of increased calls for his resignation on the eve of a critical vote in Parliament.

The European debt crisis threatened a second European government on Monday as the remnants of support for Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi of Italy seemed to be eroding rapidly in face of increased calls for his resignation on the eve of a critical vote in Parliament.

One of Mr. Berlusconi’s closest advisers, Giuliano Ferrara, the editor of the daily newspaper Il Foglio, wrote in its online edition that the prime minister was negotiating the terms of his departure, while Interior Minister Roberto Maroni acknowledged during a television program on Sunday night that Mr. Berlusconi’s coalition no longer had the numbers to govern.

The developments came as Greek leaders on Monday negotiated a transitional government to oversee their country’s debt-relief deal with the European Union after Prime Minister George A. Papandreou agreed on Sunday to step down when the new unity government was formed.

But Mr. Berlusconi is unlikely to go down without a fight.

The prime minister on Monday told Libero, a newspaper that backs the government, that he intended to face Parliament on Tuesday for a vote on a state financing bill and then call for a confidence vote on austerity measures meant to quell market concerns about Italy’s economic stability.

“I want to look at those who want to betray me in the face,” he said, denying a swirl of rumor in the Italian news media on Monday that he was about to resign.

In a statement reported by the ANSA news agency, Mr. Berlusconi said talk of his imminent resignation was “without foundation and I do not understand how it got around.”

Mr. Berlusconi spent Monday morning at his private villa outside Milan where he met with his children and Fedele Confalonieri, chairman of Mr. Berlusconi’s Mediaset media company and a close friend and adviser.

The rumors of Mr. Berlusconi’s impending resignation, and their later rebuttal by Mr. Berlusconi, sent markets seesawing. The yields on Italy’s 10-year bonds, a barometer of investor anxiety about loaning Italy money, rose to 6.63 percent, close to the level that forced Ireland, Greece and Portugal to seek financial rescues.

Calls by Mr. Berlusconi’s critics for his resignation doubled over the weekend after Italy last week agreed to allow the International Monetary Fund to monitor restructuring steps aimed at containing its ballooning debt and boosting its stagnant economy.

Mr. Berlusconi’s ability to steer Italy, Europe’s third largest economy, has been called into question by a prolonged deadlock in Parliament over the scope of sweeping changes encompassing everything from pensions to privatizations.

Lawmakers from his Peoples of Liberty party have begun to openly criticize Mr. Berlusconi, a censure that would have been unthinkable until a few months ago.

Over the past two weeks, a steady trickle of defectors has left the party. By most counts on Monday, Mr. Berlusconi had lost his majority in the lower house, where he has held on to power for nearly a year with only a handful of votes.

Battered by sex scandals and countless investigations into alleged financial improprieties within his vast business holdings, Mr. Berlusconi was ultimately backed into a corner by factors outside of Italy that he could not control.

The frailty of Mr. Berlusconi’s position was expected to become clearer on Tuesday during a scheduled vote on a budget bill.

Should the government fall, a number of outcomes are open to Italy’s president, Giorgio Napolitano, who is called on by the constitution to manage the crisis.

Mr. Berlusconi and his coalition allies have repeatedly said that the only option is an immediate return to the polls. But there is widespread aversion to the current electoral law, which has eliminated the notion of direct political representation, allowing party leaders to hand-pick their candidates.

And in the current political situation, where a myriad of centrist and leftist opposition parties are unlikely to win enough votes on their own to craft a strong majority, new elections would likely lead to only sustained stalemate.

There was also no assurance that a government different from Mr. Berlusconi’s would be any more successful in pushing through the changes demanded by the European Union and now under the watchful eye of the International Monetary Fund.

With that in mind, Mr. Napolitano could also choose an apolitical outsider to lead Parliament for the time necessary to pass changes unpopular with wide segments of the electorate. But this option, which has been adopted in other moments of political uncertainly in Italian history, is also subject to political calculations.

It is difficult “to abdicate the defense of the interests of one’s electoral base if one thinks, that, in any case, elections are not so far away,” wrote Angelo Panebianco in a front-page column in the Milan daily Corriere della Sera.

NYT

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.