If you want to discover the truth about Tripoli, you have only to visit the castle of Saint Gilles.

Instead of Crusaders, the Lebanese army is inside, and around the great 12th-century walls and at the massive doors, separating the Alawi Shias from the Sunni Muslims of Lebanon’s second city. There are armoured vehicles, truckloads of troops and Humvees and coils of sparkling barbed wire in case Syria’s violence slops over into its tiny neighbour. The Alawites have stocked up with weapons, they tell you – but this is unfair, because everyone in Lebanon has access to an automatic rifle or a pistol. The ghosts of the Lebanese civil war wake up regularly and haunt these people.

Take a visit to the Nini hospital and visit the underground surgery of former MP Mustafa Alouche, a bright, cheerful man who used to represent caretaker prime minister Saad Hariri’s Future party – until, he says, the Syrians persuaded the Saudis to persuade Hariri to force him to step down. “The city is still very quiet,” he says, “more than you would expect when you would imagine some people want to express their hatred of Syria. I’m not sure the Syrians will do anything, but if things get worse, civil war might happen – it might even end up like Libya.”

The problem, of course, is that Tripoli is scarcely two hours’ drive from the Syrian city of Homs. Many of its people have relatives over the border– this goes back to the days before the French mandate divided Syria and created Lebanon. The minority Syrian Alawites, to which President Bashar al-Assad belongs, and the majority Syrian Sunnis are represented in this lovely Lebanese city with its fine clock-tower, its wonderful mosque and souk, its ancient, rusting steam locomotives and the finest ice-cream shop in the Levant. It should be a place of happiness rather than fear.

Alouche, who is a general surgeon, says that the quiet here is “divinely controlled” – God might not like this task, I write in the margin of my notebook – but that “if there is an escalation in Syria, people are nervous that there could be some action by Sunnis in Tripoli against the Alawis. You know, when the Syrian army was in Lebanon, the Syrians used to interfere in every part of our life. I used to avoid meeting them. At one point, in 1999, they contacted me to be a ‘collaborator’. They said that Bashar al-Assad, who was on the way up, was a doctor and so was I. I said I did not want to go into politics under their support.”

Alouche, who is a general surgeon, says that the quiet here is “divinely controlled” – God might not like this task, I write in the margin of my notebook – but that “if there is an escalation in Syria, people are nervous that there could be some action by Sunnis in Tripoli against the Alawis. You know, when the Syrian army was in Lebanon, the Syrians used to interfere in every part of our life. I used to avoid meeting them. At one point, in 1999, they contacted me to be a ‘collaborator’. They said that Bashar al-Assad, who was on the way up, was a doctor and so was I. I said I did not want to go into politics under their support.”

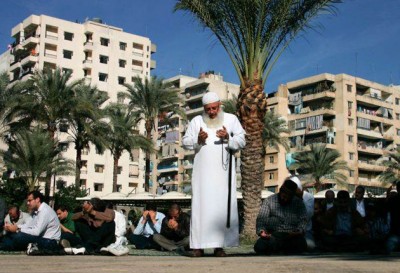

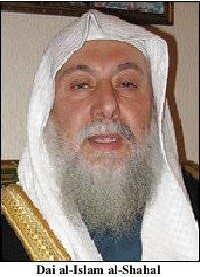

These are dangerous things for anyone to say these days and a friend has warned Alouche that his life may be in danger. “He says I am under threat, but I don’t find real means to defend myself. I am working as a doctor.” But he is not the only man who is concerned. Sheikh Da’i al-Islam al-Shahal leads the Institution of the Salafist Party in Lebanon, a big man in a white robe and a massive, equally white beard who was constantly threatened when the Syrian army and secret service were here from 1976 until 2005. He is just the kind of preacher whom their government likes to hold up as an “extremist” whom only the Baath party can handle.

“Most of the population of Tripoli are appalled at the bloodshed and oppression, the siege and invasion of the city of Deraa,” he says. “We are neighbours of the Syrians and we have many social links with them. According to the Syrian regime, the opposition has gone out of control and become dangerous – but the regime has itself brought about a catastrophe. I think they are nearing the end. They may try to hold on to power on the people’s corpses – or the country will go down to division as Gaddafi has done.”

It is the second time in an hour that Libya’s tragedy has been evoked. “We and the people of Tripoli object deeply to the human rights violations that are occurring at the cost of lives and blood,” Sheikh al-Shahal says. “It’s a terror-security state. They have no friends, no true friends. They have only self-interest. I tried to mediate at Denniyeh [where armed Islamists and the Lebanese army fought a pitched battle over 10 years ago] but the Syrians refused my mediation – they preferred a confrontation so they could say ‘the Lebanese can’t control themselves, so how much they need us ‘.”

Al-Shahal believes the Lebanese Alawis are being armed by Damascus – “they are selling themselves to their allies in Syria,” he says, “but this does not stop us offering goodwill and giving our opinions without fear. What we seek is to reach a truce through dialogue and understanding.” Al-Shahal is anxious to point out that the West misunderstands Salafism and its strict interpretation of the Koran. “We have nothing to do with violence and extremism.”

Al-Shahal believes the Lebanese Alawis are being armed by Damascus – “they are selling themselves to their allies in Syria,” he says, “but this does not stop us offering goodwill and giving our opinions without fear. What we seek is to reach a truce through dialogue and understanding.” Al-Shahal is anxious to point out that the West misunderstands Salafism and its strict interpretation of the Koran. “We have nothing to do with violence and extremism.”

But mention Osama bin Laden and he has strong views. “I think that his killing helped America but US losses will be greater,” he says. “Maybe the new head of al-Qaeda will be much more brutal. And throwing his body in the sea, this is something the Arab and Muslim world cannot accept. Throwing him to the fishes shows a bitterness that does not befit human nature. Dignity should be shown to any dead person and Islamic principles say if you die on Earth, then a piece of the Earth is reserved for you. We have a saying that ‘an excuse is worse than guilt’. What is wrong with people seeing where he is buried? Maybe they could have buried him on a far mountain where people would not go…”

I doubt that this would stop anyone visiting a Bin Laden grave, I say. But we part on good terms, some of the Sheikh’s 10 children watching from the door of the kitchen. Oh yes, and the black-market price of an AK-47 rifle in Tripoli is now said to be $1,500. Like the fishes, food for thought.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.