TO ALGERIANS, Abdelaziz Bouteflika is like Schrodinger’s cat: simultaneously alive and dead until his actual state has been observed. Occasionally Mr Bouteflika, the 81-year-old president of Algeria, who has suffered at least one bad stroke, is rolled out in his wheelchair for an appearance. In October, for example, he met Dmitry Medvedev, the Russian prime minister. A short video of the encounter showed Mr Bouteflika staring blankly into the distance and mumbling a few words. Behind the scenes, a clique of military officers and economic officials actually runs the country.

Mr Bouteflika is indicative of the decrepit state of the region’s politics. Of the 18 Arab countries and territories, nearly a third are ruled by old men in terminal decline. They are a stark contrast to the region’s young population. Whereas the median age in the Arab world is 25, among Arab heads of state it is 72. Even when lucid, the old fogeys appear out of touch with their more progressive and increasingly frustrated young subjects. And their prolonged rule leaves deep uncertainty about who will one day replace them.

While his constituents are angry about rampant corruption and the never-ending occupation, Mr Abbas spends most of his time in Amman, insulated from such concerns. And he has no clear replacement. Many fear his death will touch off a period of instability in the Palestinian territories.

Oman may be in for an even rougher transition. Its leader, Sultan Qaboos, 77, at least appears before his subjects a few times each year. He has suffered from cancer for several years. A bachelor since the 1970s, he has no heirs. The name of his chosen successor is written on a sealed envelope in his palace.

With a sprawling royal family, contenders abound. But rather than elevate potential rivals, the ailing sultan also serves as the prime minister, defence minister, finance minister and foreign minister. In his spare time, he runs the central bank. No one knows how much attention he actually devotes to this sprawling portfolio.

Other Gulf leaders are faring no better. Sheikh Sabah al-Ahmad al-Sabah, the Emir of Kuwait, is 88 and stumbles over his speeches. Khalifa bin Zayed, the nominal ruler of the United Arab Emirates (UAE), has been in seclusion since he suffered a stroke in 2014. King Salman of Saudi Arabia also appears to be fading. He keeps his speeches short and his public schedule limited. In February he presided over a humanitarian-aid summit in Riyadh organised by a charity that bears his name. But he did not say a word.

Old leaders are nothing new in the Arab world, where monarchies and dictatorships are the norm. In some countries, at least, doddering rulers have limited powers or they have transferred power to younger go-getters. Kuwait has an elected parliament and relatively liberal constitution. Real power in Saudi Arabia and the UAE rests with their crown princes, both relatively young and popular.

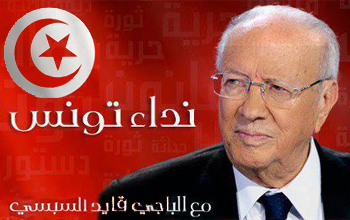

But seven years after a series of revolutions led by young people, elderly kings and presidents seem more common than ever. Even the Arab world’s lone true democracy has elected a nonagenarian. Beji Caid Essebsi, Tunisia’s president, is the oldest Arab leader, having turned 91 last year.

“They have good genes,” jokes a journalist in Lebanon, where the president is older than the country. Or perhaps just good doctors. Mr Abbas quietly checked into a Baltimore hospital for tests in February; Sultan Qaboos had his cancer treated in Germany. Those options, needless to say, are not available to many of their citizens.

THE ECONOMIST

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.