LAST week the Lebanese government announced the final list of companies eligible to bid for its first-ever round of licensing for oil and gas exploration and production, which is due to start in September. Saddled with debt greater than 140% of GDP, Lebanon could do with the revenue it would receive from exploiting its offshore hydrocarbon reserves, estimated at 850m barrels of oil and 96trn cubic feet of gas. Yet it lags behind neighbouring Israel, Cyprus and Egypt in tapping the deposits. While the existence of large fields in the eastern Mediterranean has been known since 2009, Beirut has yet to start drilling for the black stuff. Why is Lebanon taking so long to join the ranks of oil-producing nations?

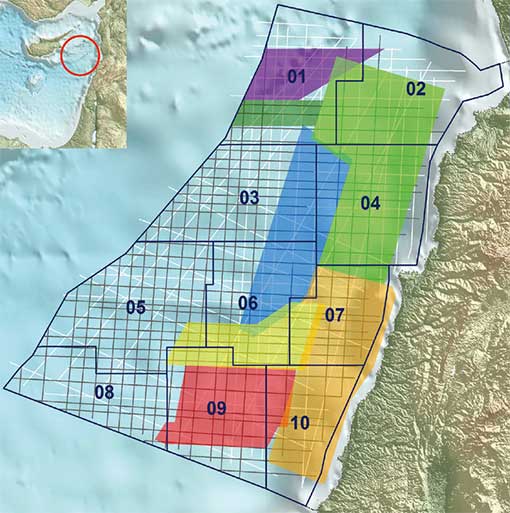

Much of the blame can be attributed to politics. In order to get the licensing process started, the government needed to approve two decrees: the first dividing Lebanon’s exclusive economic zone into ten blocs and setting their co-ordinates; the second specifying tender protocols and establishing how the oil produced would be shared between companies and the government. Yet political paralysis and sporadic violence have held up decision-making since the assassination in 2005 of Rafik Hariri, a former prime minister. Sunni, Shia and Christian factions have been jostling for influence in the government and parliament, where seats are distributed along confessional lines. Sectarian rivalries have grown even sharper since the outbreak of Syria’s civil war, with competing power centres supporting opposite sides in the conflict and disagreeing over how to manage an influx of more than 1m refugees. The political standoff resulted in a 29-month vacancy at the presidency, starting in May 2014, which delayed key decisions. No oil-and-gas auction happened after Lebanon first pre-qualified 46 companies in 2013.

The election of Michel Aoun as head of state in October has eased this stalemate. The decrees were passed in January, and a second pre-qualification round was launched shortly thereafter. But the process has not been helped by uncertainty surrounding the viability of the licences Lebanon is putting up for sale. Some of the southern-most blocs being auctioned overlap with maritime territory also claimed by Israel. Lebanon’s inclusion of a contested 860-sq-km zone in its tender disrupted what Israel says was a status quo in which neither side does anything with the disputed area. Israel responded by proposing a maritime law formalising its rights on the stretch of seabed, which Nabih Berri, the Speaker of Lebanon’s parliament, described as “a declaration of war on Lebanon”. At a time when tensions are flaring up between Israel and Hezbollah, a Lebanese militant group, investors will probably wait for the row to be solved before investing millions of dollars in exploring the contentious blocs.

Precedents are not encouraging. America has been trying for several years to broker a resolution between the two countries, which have no diplomatic relations. Calls by Lebanese authorities for the matter to be settled by the UN’s mission in southern Lebanon have so far gone unheeded. Even if these disputes are resolved, other problems persist. Should Lebanon’s reserves prove as substantial as predicted, it may have difficulties finding regional customers: the Egyptian, Israeli and Turkish governments are close to signing supply deals with each other.

The Economist

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.