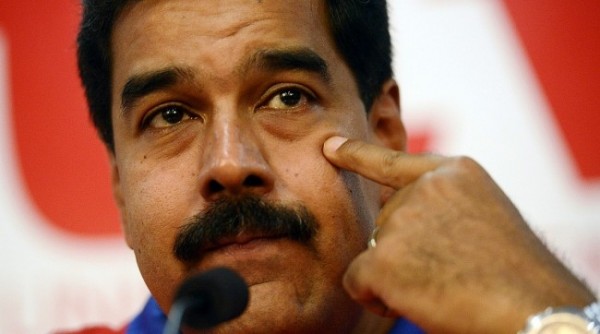

President Nicolas Maduro is facing growing, deadly unrest across Venezuela. Amid the country’s deepening economic and political crisis, the leftist leader is also increasingly isolated within the region.

Violent confrontations between protesters and police have gripped the oil-rich nation for the past month, leaving up to 25 people dead, including four on Monday and Tuesday. Often peaceful mass protests and “sit-ins” have descended into chaos, with security forces using rubber bullets and tear gas to disperse demonstrators.

The United Nations and world leaders from Spain to Peru have called on Maduro to respect protesters’ rights to peaceful assembly and free speech, many criticising a government crackdown in which around 1,400 people have also been detained.

The Catholic Church and human rights groups have joined the anxious chorus, urging Maduro to find a peaceful resolution to the unrest and to take protesters’ demands seriously. The opposition is calling for new elections, the release of jailed activists and independence for Venezuela’s conservative-led congress.

Maduro, who has denounced the protests as a “coup” attempt, could once have turned to like-minded Latin American leaders in times of crisis. But in the current upheaval threatening to unravel 15 years of Socialist rule in Venezuela, Maduro suddenly seems to be short of friends.

“The return of right-wing governments, particularly in Brazil and Argentina, are a hard blow to Maduro and give him fewer diplomatic options,” said Franck Gaudichaud, a French university professor and an expert in left-wing politics in Latin America.

Indeed, Argentina’s Cristina Fernandez and Brazil’s Dilma Rousseff – steadfast allies of Maduro and his late predecessor Hugo Chavez – were swept out of power in the past two years. They have been replaced with conservative administrations that Gaudichaud says are “very hostile” to Maduro and the left-wing Chavista legacy.

Regional allies remain, namely Bolivia and Ecuador, but they lack the influence of the regional powerhouses of Brazil and Argentina, and even those two Andean nations seem reticent to give Maduro unconditional backing.

In reference to the protests, and taking a cue from Maduro, Bolivian President Evo Morales declared on Twitter earlier this month that the “imperialist” US military was threatening Venezuelan “sovereignty”. He nevertheless added that Bolivia would defend a “peaceful resolution” to the conflict in Venezuela.

“It was a tepid declaration by the simple fact that Morales was effectively calling for negotiations,” Gaudichaud said, adding statements of support for Venezuela in the past have been much bolder.

Meanwhile, Ecuadorian President Rafael Correa has remained mum on the subject. His 10-year tenure as president is ending on May 24, and president-elect Lenin Moreno – who hails from the same left-wing party – has likewise avoided public remarks on the Venezuelan crisis.

Shifting power

Another sign of Maduro’s isolation is the waning influence of the intergovernmental organizations Chavez used to buttress his “Bolivarian revolution”: the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR), the Mercosur trading block, and the left-wing Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America (ALBA) may have once been able to help legitimise Maduro’s government and steer it through times of trouble, but no longer.

UNASUR, which is modelled on the European Union and headquartered near the Ecuadorian capital of Quito, has shown little interest in intervening in the Venezuelan crisis. Mercosur, which Venezuela joined in 2012 and which includes Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay and Paraguay, last year moved to force Venezuela out of the group. As for ALBA, Gaudichard says it has been reduced to “an empty shell” that “doesn’t work at all”.

As UNASUR and ALBA lose clout within the region, “power has shifted back to the Organization of American States (OAS), where the United States has a much stronger influence”, according to Gaudichard.

OAS chief Luis Almagro is leading a push to make Maduro hold general elections that the Socialist camp would likely lose. Almagro has threatened to go as far as suspending Venezuela from the regional block over its response to the protests.

Gaudichard says Venezuela has reason to be worried about interference in its affairs by the OAS and by Washington, given the long history of US meddling in Latin America. He nevertheless believes regional neighbours and groups could still play an instrumental role in resolving the deepening crisis.

“Help from neighbouring countries in the 1980s helped Central American countries overcome much bloodier and deep-rooted civil conflicts than the one Venezuela is experiencing today,” the academic said, pointing to the Colombian peace agreement as a more recent example of fruitful regional engagement.

Hosted in Cuba, the long but eventually successful peace talks were additionally sponsored by Venezuela and Chile, and even counted with the tacit support of the United States. Even though regional ties have been stretched and blurred as Latin America undergoes a political shift away from the left, they could offer the lifeline Venezuela desperately needs.

FRANCE 24

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.