Iraqi and Kurdish military and paramilitary units are preparing for a push on Mosul, the Islamic State-held city that is now in the cross hairs of the U.S.-led coalition battling the terrorist group across the Middle East. “The idea is to isolate Mosul, cut it off, kill it,” a senior U.S. Central Command officer told me.

Senior military officers say the city in northern Iraq, which has been under Islamic State control since June 2014, will be enveloped in a complex pincer movement from Iraqi military forces battling their way into the city from the southeast and Kurdish units storming the city from the northwest. The military offensive, months in the planning, is now tentatively scheduled to begin sometime in early October, with a final battle for Mosul coming at the end of that month.

If Mosul is retaken, it would both mark a major political triumph for Barack Obama and likely benefit his party’s nominee at the polls, Hillary Clinton, undercutting Republican claims that the Obama administration has failed to take off the gloves against the Islamic State. Even so, senior officers at U.S. Central Command who are overseeing the effort scoff at the notion that the Mosul offensive is being timed to help the candidate Obama is now actively campaigning for, his former secretary of state.

“Hurrying this thing along for political benefit would be just about the dumbest thing that we could do,” the senior Centcom officer told me this week, “and there’s been no pressure for us to do that. None. Iraqi and Kurdish fighters are going to fight for the city when they’re damned good and ready, and not before. There’s too much at stake to do it any other way.”

All evidence supports that notion, but U.S. officials have confirmed the Pentagon is planning ways to time their offensive against Mosul with an attack on the Islamic State “capital” in Raqqa, Syria. A coordinated Mosul-Raqqa military offensive could yield a dual defeat to the ISIS caliphate, unhinge ISIS power in both Syria and Iraq and have the added benefit of pinning ISIS units moving into Iraq along interior lines from Syria in place. In late March, the Centcom stepped up its monitoring of the Syria-Iraq border, with the intended purpose of spotting and bombing ISIS units headed toward Mosul.

The ambitious plans for Mosul and Raqqa reflect a shift in tactics and deeper U.S. involvement that has not been fully reported in the U.S. media—or talked about in the presidential campaign. Most recently, Centcom has gained White House permission to deploy U.S. advisers with Iraqi units at the battalion level, which would place U.S. advisers and trainers in greater danger, but would also give them more control of the battlefield. And the U.S. has been quick to flow advisers (an initial tranche of some 200 in all) into al-Qayyarah air base, about 40 miles south of Mosul, which was overrun by Iraqi military forces last week. Washington has also boldly stepped up its support of the Peshmerga, the veteran military units of the Kurdistan Regional Government who will lead the assault on Mosul from the north, despite the risk of upsetting the delicate regional politics—especially suspicions by the Shia-led Iraqi government that the U.S. is favoring the Kurds. On July 12, the U.S. signed an agreement with the KRG to provide Peshmerga units with $415 million for the purchase of ammunition and medical equipment. The agreement would also provide heavy weapons to Peshmerga units, which have been consistently outgunned by ISIS fighters, according to one senior civilian Pentagon official. The $415 million would correct that shortfall, with weapons flowing into Peshmerga units near Mosul.

The stepped-up aid to the Kurds reflects U.S. military confidence that the Islamic State is being rolled back. Since the campaign was initiated on August 8, 2014, the U.S.-led coalition has launched over 13,000 airstrikes on Islamic State military targets. Just as crucially, the four near-term goals laid out by the U.S. military to combat ISIS are on the verge of completion: to stabilize Anbar, prepare coalition ground forces to take Mosul, organize a ground campaign in Syria for a planned assault on Raqqa and ramp up the flow of weapons for anti-ISIS ground forces.

A dual offensive targeting Raqqa as well as Mosul was hinted at by Lt. General Sean MacFarland, the U.S. officer commanding the anti-ISIS effort, in a July 11 news conference. Seizing control of Raqqa, he said, would mean that ISIS would “lose a base of operations, would “lose financial resources” and would “lose the ability to plan, to create the fake documentation that they need to get around the world.” Centcom military planners say that, from a U.S. military perspective, the fight for Raqqa will be even more important than the fight for Mosul.

“It is clear who will be in the Mosul fight,” former Syrian diplomat Bassam Barabandi told me this week, “but just who will take part in the Raqqa fight is not so clear. It is being negotiated now. But I don’t think there’s any doubt, it will be Raqqa and Mosul, and Iraqi officials have confirmed that they would like to take the city in October.”

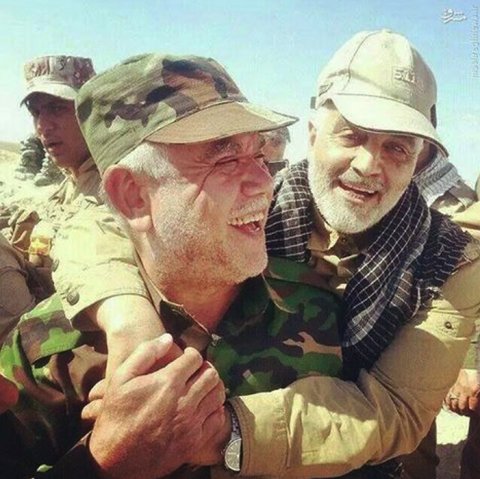

The fight for Mosul will be done by a trifecta of military forces: Iraq’s Popular Mobilization Forces (the controversial Hashd al-Shabi), the Peshmerga and Iraqi Security Forces, large numbers of whom are being trained by U.S. advisers. The U.S. is uncomfortable with the predominantly Shia Hashd forces leading the assault, as they are only nominally controlled by the Baghdad government and have proved recalcitrant in taking American advice. Formed in June 2014 after Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani called on Shias to fight ISIS, some elements of the Hashd are closely aligned with the Iranian al-Quds force, with their commander reporting to Iranian commander Qasem Soleimani.

But according to Robert Tollast, a U.K.-based military analyst who has traveled to Iraq and spoken with a number of Hashd commanders, Hashd is proving to be a bigger help than ever; the group is increasingly recruiting Sunni tribesmen eager to expel ISIS from their towns and villages. “We’re seeing a replay of what happened during the Anbar Awakening,” Tollast says. “ISIS brutality has forced a lot of Anbar’s Sunnis into an alliance with Hashd, just as, back in 2006, Al Qaeda’s brutality forced the Sunnis into the arms of the Americans.” Crucially, the Islamic State’s cultural cleansing of Anbar has begun to increase the appeal of Hashd units to Anbar’s Sunnis, the exact opposite of ISIS’s strategy of maintaining and exacerbating Iraq’s sectarian divide.

But while Sunnis in increasing numbers are now joining the fight against the Islamic State, their presence has not always been welcome by Iraqi Shias already doing the fighting. “The Shias view ISIS as just another form of Sunni Baathism,” Tollast says. In this, at least, they are not wrong: The senior leaders of ISIS were often prominent in the Saddam’s Baath Party, which brutally suppressed Shias during his nearly 25-year rule. The divide is deep. During a recent trip, Tollast had a meeting with a Shia leader whose office included a poster depicting Baathist Republican Guardsmen executing Shia civilians in 1991. Tollast told me that the parallel to the June 2014 Camp Speicher massacre, in which an ISIS unit commanded by a former Saddamist murdered over 1,500 Iraqi Air Force cadets, all of them Shia, was unmistakable.

All of which helps explain why the Kurdish Peshmerga are considered a mainstay of the Mosul operation; U.S. military officials have enormous faith in the Peshmerga’s fighting abilities, even as the strong U.S.-Kurdish relationship has proved difficult for the Iraqi central government (which recently accused Peshmerga forces of arresting and torturing Iraqi army soldiers), as well as the commanders of a variety of Popular Mobilization Force units. Turkey is another key player, since the neighboring country also fears growing Kurdish influence with the U.S.—especially since the failed coup attempt earlier in July, which the Turkish government has blamed on a Muslim cleric living in exile in Pennsylvania—as Turkey jockeys for position in a post-conflict Mosul against the PKK, the Kurdistan Workers Party, which now controls an arc of territory from northern Iraq into northern Syria. So far, the fight against ISIS has provided the glue for a tense, if uneasy, truce among these political factions—but U.S. officials concede the informal alliance on the battlefield could be shattered by political disagreements.

According to the senior Pentagon official, the recently negotiated U.S.-Kurdish understanding came with strings attached, including Peshmerga battlefield coordination with Iraqi Security Forces operating on the Mosul front. Peshmerga commanders, according to this official, have now agreed to stand aside when the Iraqi Security Forces pass through their units during the initial assault on Mosul. The move is part of a U.S. effort to make sure that the units involved in the Mosul fight don’t end up battling each other. The memorandum of understanding was signed in Erbil, with the Americans represented by acting Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Security Affairs Elissa Slotkin. It was Slotkin who, back in January of 2015, gave the cold shoulder to Sunni Anbar leaders who came to Washington to plead that the U.S. government bypass the Baghdad government to arm them directly. The U.S. refused.

While the refusal of the Obama administration to arm Anbar’s Sunnis met with widespread criticism on Capitol Hill, the administration still maintains that arming the Sunnis directly would be a mistake. In the wake of the visit by Anbar Sunnis in 2015, the administration quietly responded to its critics by pointing out that large numbers of weapons the U.S. had provided the tribes during the Bush years had ended up in the hands of ISIS. “They’re nice people, they mean well,” an administration official told me at the time. “But we can’t trust them.”

The U.S. continues to insist that all support for Anbar’s Sunni tribes be funneled through Iraq’s Ministry of Defense. But while the U.S. is still saying “no” to Anbar leaders who demand the U.S. bypass the Iraqi government in supporting them, the answer now is more nuanced: It’s more of a “no, but … ” More regular support for Anbar’s Sunnis is now possible, U.S. officials say, because the Defense Ministry is under the control of Khaled al-Obaidi, a Sunni from Mosul who has made it a point of touring Iraq military units preparing to storm the town. Obaidi’s appointment in October 2014 was widely criticized by Iraq’s Shia political parties, and there was an assassination attempt on him last September, when his convoy was hit by sniper fire north of Baghdad. Despite the controversy over his appointment, the U.S. told Iraqi Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi that Obaidi’s presence was essential in the anti-ISIS fight because it would help to heal the rift between the Shia dominated government and Anbar’s tribes.

Still, Sunni tribal leaders complained throughout the early part of 2015 that the Iraqi government was slow to provide them with the weapons they needed. So last October, Pentagon officials say, Defense Secretary Ash Carter increased pressure on the Iraqi government to accelerate weapons’ deliveries to Anbar’s newly created Tribal Mobilization Force. Carter told the Congress that the U.S. had provided “two battalions’ worth of equipment for mobilizing Sunni tribal forces,” adding that it was up to the Iraqis to “ensure it is distributed effectively.” He added that “local Sunni forces need to be “sufficiently equipped and regularly paid.”

What Carter didn’t say, but the Pentagon officials now confirm, is that the U.S. has also channeled funding support to key tribal leaders through Obaidi’s ministry, as a kind of replay of the financial support that helped jump-state the Sunni Awakening in 2006. While the new Tribal Mobilization Force cannot match the combat power of the Hashd al-Shaabi (Anbar’s Sunnis can contribute 10,000 soldiers to the Mosul effort, at most, one Centcom officer says), its participation is essential as a symbol of the Abadi government’s attempt to build an anti-ISIS coalition of diverse Iraqi forces. (Suhaib al-Rawi, Anbar’s governor, said he preferred to withhold any comment on this report.)

The fight for Mosul and Raqqa will likely be a turning point in the war against ISIS. But while no one in Baghdad or Washington is guaranteeing victory, the U.S.-led coalition’s control of the air and the continued degradation of ISIS’s battlefield assets (they have lost nearly 150 tanks and over 7,000 reinforced fighting positions, according to Centcom’s precisely tabulated data), means that the Mosul fight could follow the model provided by the Battle for Fallujah, which the Iraqis reconquered from ISIS back in June. In that case, according to Joel Wing who charts events in the country and writes the “Musings on Iraq” blog, “there were tougher outer defenses and then little in the interior.” Mosul, he says, could be “even more like that.” Then too, he adds, the fight for Mosul has become so important that “everyone wants in on it.”

That’s the good news. The bad news is that while the broad U.S.-led coalition to fight ISIS remains unified, the same cannot be said for the forces on the ground. The only thing that unites them, it seems, is that they hate ISIS more than they hate each other. So while senior U.S. military officers are confident that a final assault on Mosul will succeed, they also know that the offensive could break apart even before it is launched.

Which means that while Obama would welcome an October surprise, he continues to caution that the fight against ISIS could take years. And it’s why Prime Minister Abadi has ignored calls that he expel U.S. military advisers, that he seize control of the Shia-dominated Hashd al-Shabi, that he dismiss Obaidi, that he cease all support for Anbar’s Tribal Mobilization Force and that he get tougher with the Kurds. And that’s because Abadi knows that the fight for Mosul is a battle Iraq can’t afford to lose.

POLITICO

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.