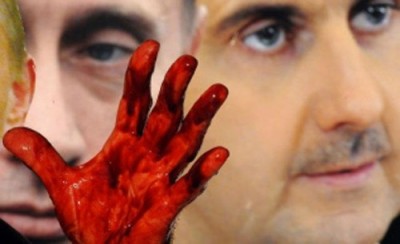

Russia will countenance Syrian President Bashar al-Assad leaving office, but only when it is confident a change of leader will not trigger a collapse of the Syrian government, sources familiar with the Kremlin’s thinking say.

Getting to that point could take years, and in the meantime Russia is prepared to keep backing Assad, regardless of international pressure to jettison him, those sources said.

Such steadfast support is likely to further complicate already stalled peace talks with Assad’s opponents and sour relations with Washington which wants the Syrian leader gone.

“Russia is not going to part company with Assad until two things happen,” Sir Tony Brenton, Britain’s former ambassador to Russia, told Reuters.

“Firstly, until they are confident he won’t be replaced with some sort of Islamist takeover, and secondly until it can be guaranteed that their own position in Syria, their alliance and their military base, are sustainable going forward.”

The Kremlin, which intervened last year to prop up Assad, fears turmoil in his absence, thinks his regime too fragile for major change, and believes there’s much fighting to do before a transition, say multiple Russian foreign policy sources.

Russia and the United States are co-sponsors of peace talks between the warring sides in the Syria conflict. Those talks, currently on hold, have so far carefully skirted the question of whether a peace deal would require Assad’s departure, so negotiations could theoretically limp along despite the contradictions between the positions of Moscow and Washington.

Moscow has signaled its support for Assad has limits. Russian diplomats have said the Kremlin is backing the Syrian state, not him personally. President Vladimir Putin has said it would be worth considering how members of the opposition could be incorporated into Syrian government structures.

Such talk has fueled Western hopes that Russia might help broker Assad’s exit sooner rather than later.

But sources close to the Kremlin say there are no meaningful signs Russia is ready to cut him loose anytime soon.

“I don’t see any changes now (in Russia’s position on Assad,” said Elena Suponina, a senior Middle East analyst at the Moscow-based Russian Institute for Strategic Studies, which advises the Kremlin. “It’s the same and why change it?”

DOUBLING DOWN

On the contrary, state media, which toes the Kremlin’s line, suggests Russia is instead doubling down on Assad and trying to shut down any U.S. attempts to discuss his future.

Dmitry Kiselyov, presenter of the main weekly TV news show Vesti Nedeli, told viewers this month that a surprise visit to Syria by Russian Defence Minister Sergei Shoigu was a message to Washington to stop trying to pressure Moscow over Assad.

“Shoigu’s visit and his meeting with Assad is a definite signal from Russia,” said Kiselyov, reputed to be one of Putin’s favorite journalists.

“Who is it the Americans want to see in Assad’s place? Nobody in Washington, including Obama, has explained.”

Fyodor Lukyanov, a foreign policy expert close to the Kremlin who edits the Russia in Global Affairs journal, said there had been talk inside the Russian government about Assad’s future and that he thought a deal was there to be done one day.

But he told Reuters Russia’s current position was “wait and see”, that the Kremlin wanted to first see who became the next U.S. president, and that it would need a lot of time to come up with a plausible alternative to Assad if and when it wanted to.

“How do we know if we remove him the whole system is not going to collapse,” said Lukyanov. “There is a risk of that.”

ISLAMIST THREAT

The Kremlin says thousands of Russian and former Soviet citizens are fighting in Islamic State ranks and that they must be defeated in Syria and Iraq to prevent them from returning home to launch attacks.

It casts Assad, whose father Hafez was a longtime Moscow ally in the Soviet era, as its chief partner in that battle.

Andrey Kortunov, director general of the Russian International Affairs Council, a Moscow-based foreign policy think tank close to the Russian Foreign Ministry, said there was not a lot of sympathy for Assad personally inside Russian foreign policy circles.

But he said Moscow had to position itself as an important and victorious player and that Assad was part of that equation for now.

“You must remember the other side of the coin,” he said. “Russia is important because it has relations with the Syrian regime so if it sacrificed that relationship it might cease to be a player.”

Tarja Cronberg, a Russia expert who used to be a Finnish government minister, said Russia might agree to a deal on Assad’s exit that retained key parts of the state’s structure and political elite while integrating opposition politicians.

But finding an arrangement that combined those elements would not be easy or quick.

“The question really is how to create stability and change at the same time,” she said.

For now, Brenton, the former British ambassador, said in the eyes of Putin and his advisers see Assad’s role as a bulwark against radical Islam trumped everything else.

“For them, Assad, for all his disadvantages and for all his bloodiness and unpleasantness, is preferable to yet another country falling into Islamist hands,” he said.

REUTERS

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.