By Michael Hirsh, a senior correspondent at Foreign Policy.

‘Not One but Two Cold Wars’

Fifty years ago this month, in one of the diplomatic masterstrokes of the Cold War, U.S. President Richard Nixon arrived in China on a surprise visit that drove a deep wedge between Beijing and Moscow. Today, many observers fear that Washington is doing the opposite: driving China and Russia closer together and risking military conflict simultaneously with both nations.

Beijing and Moscow have demonstrably stepped up their military cooperation in recent years, holding joint war games and sharing aviation, submarine, and hypersonic-weapons technology. Motivated in large part by a common opposition to U.S. policy, Chinese leader Xi Jinping and Russian President Vladimir Putin also have gingerly endorsed each other’s right to threaten independent nations that each leader considers a breakaway territory—respectively, Taiwan and Ukraine.

The Biden administration has found itself locked in confrontation with both countries and, most imminently, facing a possible invasion of Ukraine by Russia. On Feb. 4, Putin pointedly met with Xi in Beijing ahead of the Winter Olympics, an event that U.S. President Joe Biden and other Western leaders boycotted. The Russian and Chinese leaders later issued a joint statement opposing “further enlargement of NATO”—Putin’s key demand regarding Ukraine, which he fears will join the alliance—as well as “any forms of independence of Taiwan.” The 5,300-word statement included an unprecedented pledge by the two countries to lead a “redistribution of power in the world” as part of a “no limits” strategic partnership.

Biden pooh-poohed the Xi-Putin meeting, telling reporters: “There is nothing new about that.” Senior Biden officials echoed that point, saying that the United States wasn’t especially worried, particularly since Washington has a lot more alliance power than both countries put together. The United States and its Western allies “are 50 percent-plus of global GDP. China and Russia are less than 20 percent,” U.S. National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan said Feb. 11, adding that “we are well situated to be able to deal with any threat or challenge that would be posed to us by any autocracy in the world.”

The China-Russia relationship has clearly deepened in recent years. After a three-day visit to Moscow in 2019, Xi described Putin as his “best friend and colleague.” According to a report by the Center for a New American Security, Russian arms now account for some 70 percent of China’s arms imports overall, and Beijing has been eagerly buying Su-27 and Su-35 fighter aircraft, S-300 and S-400 air defense systems, and anti-ship missiles. Moscow, in turn, “has turned to China for electronic components and naval diesel engines that it previously bought in the West, blunting the impact of Western sanctions,” the report said.

China and Russia are also cooperating in new ways in undermining democracy: Russia, for example, recently purchased internet firewall technology from China. According to an exhaustive study of the China-Russia relationship published by the Rand Corp. late last year, the two nations can be expected to ratchet up collaboration in research and development “such as with hypersonic glide vehicles, counter-space systems, and artificial intelligence; and expand military coproduction agreements.”

The Rand study concluded: “The net impact would be an overall increase in the capacity, sophistication, and interoperability of the two militaries, especially in the domains where they anticipate confronting the United States.”

Most experts still reject the prospect of a full-blown security alliance between China and Russia. For Beijing, in particular, the economic consequences could be devastating: China does vastly more trade with the European Union than it does with Russia, and despite current trade tensions the United States remains China’s largest trading partner, taking in nearly half a trillion dollars a year in Chinese goods and services. Even so, a 2019 assessment by the U.S. Office of the Director of National Intelligence reported that Beijing and Moscow “are more aligned than at any point since the mid-1950s.” The report said, “the relationship is likely to strengthen … as some of their interests and threat perceptions converge, particularly regarding perceived US unilateralism and interventionism and Western promotion of democratic values and human rights.”

In other words, the two Eurasian giants may well be approximately back to where they were as Cold War allies, before the Sino-Soviet split of 1961—the split that Nixon and his national security advisor, Henry Kissinger, brilliantly exploited by engaging with Beijing 50 years ago.

A key issue now is whether Beijing and Moscow are also working together to test U.S. and Western resolve. Another parallel to 50 years ago is that the United States is perceived as weak and internally divided. Will China and Russia find a way, together, to neutralize U.S. power and influence?

“I think the Russians are setting us up for something the Chinese will later do. They both think in the same way,” said former senior U.S. diplomat Chas Freeman. He said the two countries are united in opposing a hostile Washington they believe is pressing up against their territories, and if nothing changes they will respond in kind. “For Putin I don’t think this is about Ukraine only. It’s about a process of escalating pressure that may see him placing submarines with hypersonic missiles five minutes away from D.C. and New York. I think the Chinese will eventually be drawn to do the same. We’ve been running mock attack runs on Chinese ports; now they claim over 2,000 intrusions by us in the last year. At some point, they’re going to respond in kind off San Diego and Puget Sound, and eventually Norfolk.”

Freeman, a China expert who interpreted for Nixon during his historic trip 50 years ago, said the Biden administration has been misreading Beijing in particular—mainly in an effort to “posture for political effect” and look tough on Capitol Hill. “What we’ve been doing absolutely wrong is challenging Chinese ‘face’ wherever we can,” he said. Biden’s team, in particular Secretary of State Antony Blinken, “have absolutely no sense of how to manage cross-cultural communication,” Freeman said. “You can’t go into a meeting and denigrate the other side and expect to get anything but an angry reaction, and that’s what we got. This is asinine. This is not diplomacy.”

Last October, in what some interpreted as a breach of the official policy of “strategic ambiguity” toward Taiwan that has prevailed since Nixon’s opening, Biden suggested he would come to Taiwan’s defense if China attacked. The administration later reaffirmed its adherence to strategic ambiguity, but Biden’s statement raised the temperature after a tense meeting in Alaska in March 2021, when Blinken harshly criticized Beijing’s brutal campaign of suppression in Xinjiang and Hong Kong, and its threats to Taiwan. “Each of these actions threaten the rules-based order that maintains global stability,” Blinken said, adding that China’s cyberattacks on the United States and economic coercion against U.S. allies were equally unacceptable. The Chinese responded with angry denunciations. This January, the Chinese ambassador to Washington, Qin Gang—using blunt language formerly uncharacteristic of Chinese diplomats—told NPR that if the confrontation over Taiwan persists on its current course, “it most likely will involve China and the United States, the two big countries, in military conflict.”

Earlier this month the Biden administration released a new Indo-Pacific strategy that said the U.S. objective is no longer trying to change China into a democracy or free market economy but rather “to shape the strategic environment in which it operates.” Biden plans to achieve this, in part, by beefing up Washington’s relations with U.S. allies and partners in the region, especially the so-called Quad, which is made up of the United States, Japan, India, and Australia.

Yet key U.S. allies and partners are worried that, without some new diplomatic initiative, Washington is headed for endless, possibly disastrous, bouts of brinkmanship with both its two biggest rivals, China and Russia. The Rand study found that, “If Washington continues down the path of simultaneous heightened great-power competition with Beijing and Moscow, then a possible outcome is that it will become engaged in not one but two cold wars.”

Not least among these worriers is India, which finds itself caught in the middle of the Russia-China alignment—both geographically and geopolitically. “It defies common sense for the U.S. to take on two powerful military adversaries at two ends of the Eurasian landmass at the same time,” said Gautam Mukhopadhaya, a former senior Indian diplomat. “From India’s point of view, the U.S. should make a rational decision on who is the greater threat, Russia or China, and make some concessions accordingly as Nixon and Kissinger did with China vis-a-vis the Soviet Union in 1972.” Mukhopadhaya continued: “India also fears that this would marginalize India’s concerns over China over a range of issues, most of all on the Line of Actual Control [the 2,100-mile Indian-Chinese border] and strengthen China’s hand in the process.” Since 2020, Chinese and Indian troops have engaged in several new hostile actions along the Sino-Indian border.

Biden tried to head off the double China-Russia threat by seeking, initially at least, to assuage Putin over NATO expansion into Ukraine. Prior to Putin’s recent aggression, the U.S. president even provoked cries of appeasement from some hawks in Congress by appearing to do a “reverse Nixon” and seeking to co-opt or neutralize Putin. He offered the Russian autocrat a summit without conditions, as well as new talks over the START arms agreement. Biden also waived sanctions on Russia’s Nord Stream 2 natural gas pipeline and, in January, suggested that a divided NATO might not firmly respond to a “minor incursion” by Putin into Ukraine.

Biden’s diplomatic outreach, however, may have only encouraged Putin’s aggression. Some diplomats believe the Russian autocrat was seeking to take advantage of the Biden team’s often-stated desire to concentrate on China as America’s “biggest geopolitical test of the 21st century,” in Blinken’s description. “Putin may be actually trying to use tensions between the U.S. and China to renegotiate a new Russia-West modus vivendi over NATO in Europe (albeit through a dangerous brinkmanship that the U.S. felt it had to call the bluff on),” Mukhopadhaya said in an email.

Putin was also likely encouraged by the debacle of Biden’s Afghanistan withdrawal, which prompted outspoken criticism of Washington from European allies last year. “It seems very likely Putin looked at the situation and saw a moment of unique distraction and division in the West, and thought this was the time to move,” said Constanze Stelzenmüller, a Europe specialist at the Brookings Institution.

But Putin seems to have miscalculated. In recent weeks NATO has closed ranks as Biden has raised the stakes against Russia, announcing that about 2,000 U.S.-based troops are heading to Poland and Germany, while shifting 1,000 from Germany to Romania. “I suspect that the Kremlin and Putin have been unpleasantly surprised by the solidity of Western resistance and resolve,” Stelzenmüller said. China is watching closely as well, and Washington and some of its allies are well aware of how their response to Putin’s aggression—whether it is deemed weak or not—might influence Beijing’s calculations over Taiwan. On Feb. 16, Biden said he was still looking for diplomatic “offramps” to the Ukraine standoff.

Can Biden, faced with authoritarian governments in Beijing and Moscow that are aligned against the democratic West, find any pragmatic way of winding down tensions with one or both? Such a realpolitik approach is politically hazardous, with the president navigating a closely divided Congress amid an atmosphere in Washington of hawkishness toward both China and Russia. Some critics say the administration has too often pandered to such sentiments, deploying self-righteous rhetoric that is only inciting Beijing and Moscow to grow even closer.

The biggest danger, perhaps, is that absent a more nuanced approach to both these rival nations, Washington is in for a long-term confrontation with both—risking war with two heavily nuclearized military powers. As Kissinger himself said at a 50th anniversary event held in Beijing last July to mark the beginning of his secret diplomacy with China, Washington and Beijing in particular “should start from the premise that war between our two countries will be an unspeakable catastrophe. It cannot be won.” Freeman’s warning was equally blunt: “If you’re going to go in search of dragons to destroy, they’re going to follow you home.”

‘This Will Shake the World’

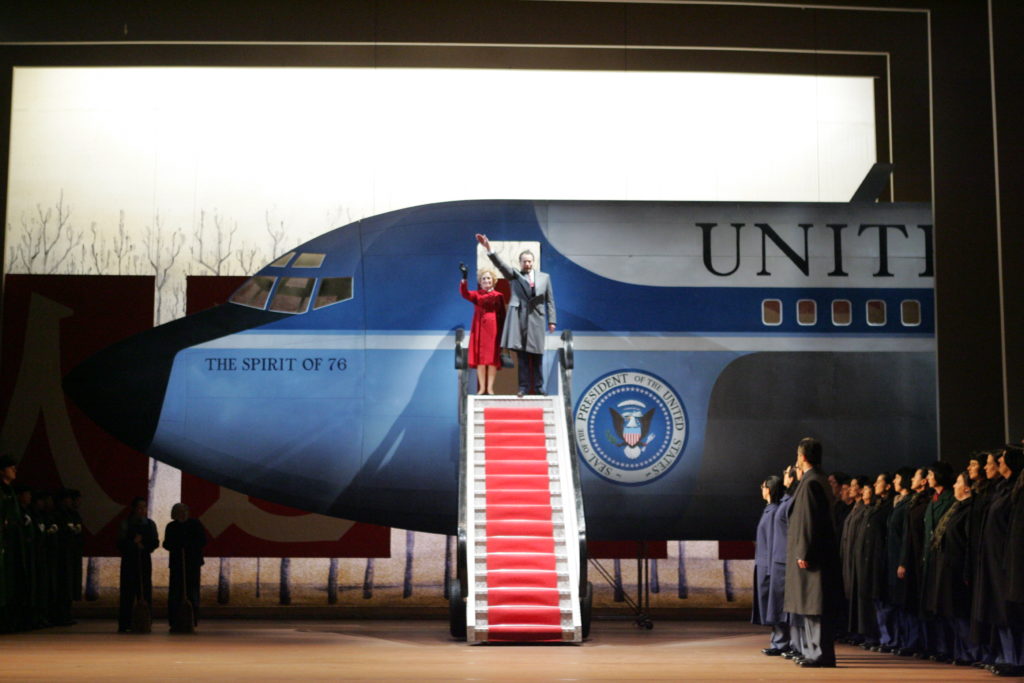

Most people, even diplomats, generally aren’t aware they’re making history at the moment they’re doing it. Nixon’s trip to China was different. After seven months of secret diplomacy, everyone who joined him for his arrival in Beijing on Feb. 21, 1972, was fully cognizant of its historic nature. Not least, Nixon himself. “I have never seen a president prepare more extensively for a trip,” Winston Lord, Kissinger’s key aide on that trip and later ambassador to China, recalled in an interview. “Before leaving Washington Nixon had marked up countless pages of six thick briefing books that I had assembled from government agencies. And then, as we flew to China via Hawaii and Guam on Air Force One, he kept asking us for even more information and details.”

As Air Force One taxied on the Beijing tarmac, Nixon instructed everyone to remain on board while he strode forth to shake Premier Zhou Enlai’s hand. “He wanted photos to capture this moment in isolation to contrast for Zhou, and the world, with the 1950s incident in Geneva when then-Secretary of State [John Foster] Dulles had refused to shake Zhou’s hand,” Lord said. Beijing and Washington had been bitter enemies with no diplomatic relations since the Korean War. Thus one of the most dramatic moments of the visit was also one of the first: the image of a smiling Nixon, dressed in a gray winter coat, warmly greeting Zhou at the bottom of the airplane stairs. “We were in one move opening up to one-fifth of the world’s people,” Lord said.

Yet the opening also came to be romanticized later as a decisive turnabout in Cold War tensions, when in fact it was a touch-and-go affair, filled with second-guessing, rancor, and enduring ambiguities. At one point in the negotiations leading up to the summit, even the aristocratic, smooth-talking Zhou—whom Kissinger called “one of the two or three most impressive men I have ever met”—summarily dismissed Kissinger’s draft communique, which “tended to emphasize the positive elements of the opening,” Lord recalled. “After one night Zhou came back and scornfully said, ‘This has no credibility. We fought each other in Korea, we’ve been enemies for 22 years, and you suddenly want to make it look like we’re prospective allies.’ He said we should try a different approach, namely each side will state differences both ideological and on specific issues, and then where we can agree we’ll look more credible.”

Kissinger quickly agreed to the unusual terms, and Lord remembers staying up until 4 a.m. to redraft the document, which addressed South Asia, the Middle East, Vietnam, Korea, and bilateral relations while leaving the explosive issue of Taiwan open. The communique was fairly well precooked by the time Nixon got to China. But Taiwan provoked another near-blowup after the Chinese Politburo had approved it. Kissinger and Nixon had excluded Secretary of State William Rogers and his deputy Marshall Green from the initial negotiations. When Rogers and Green finally saw the original draft language on Taiwan, which they believed made Nixon look soft on Taiwan, they declared “that the communique could be a disaster,” Lord recalled. “They said that President Nixon could get killed at home and around the world, and that we had given in too much to the Chinese.”

Nixon feared that Rogers and Green would leak that they had been excluded from the talks and that the president had sold out Taiwan. So he sent Kissinger back to renegotiate. At Green’s suggestion, Kissinger removed a statement in the U.S. draft that reaffirmed U.S. alliances around the world but excluded Taiwan. “That suggested echoes of Dean Acheson,” said Lord, referring to the then-secretary of state’s infamous 1950 speech excluding Korea from America’s defense perimeter, thus inviting the Soviet-backed Korean War. “He said, let’s take out any mention of alliances, so Taiwan’s absence would not stick out.”

The final result, known as the Shanghai Communique, did just that. It also left the issue of Taiwan officially open, with the U.S. side calling for “a peaceful settlement of the Taiwan question by the Chinese themselves.” The communique vaguely noted “that all Chinese on either side of the Taiwan Strait maintain there is but one China and that Taiwan is a part of China.” While Kissinger, in a gesture to U.S. hard-liners, did manage to declare in Shanghai that the United States would continue to have a defense relationship with Taiwan, Nixon and subsequent presidents also made clear that Washington would no longer oppose Beijing’s political claims to Taiwan. “Nixon’s initiative conveyed America’s acceptance, for the first time, of the outcome of the Chinese civil war,” the journalist James Mann later wrote. “The United States stopped challenging the Chinese Communist Party’s authority to rule the country.”

In the end the Shanghai Communique was a masterpiece of what came to be known as “strategic ambiguity.” “The basic theme of the Nixon trip—and the Shanghai Communiqué—was to put off the issue of Taiwan for the future, to enable the two nations to close the gulf of twenty years and to pursue parallel policies where their interests coincided,” Kissinger wrote in his memoirs. But the communique did contain one clear phrase, one that might even be, with a renewal of practical diplomacy, relevant to today’s standoff. The final document said that neither nation “should seek hegemony in the Asia-Pacific region and each is opposed to efforts by any other country or group of countries to establish such hegemony.”

The knock-on effects of the Shanghai Communique were far-reaching. “It restored U.S. credibility on the world stage,” Lord said, and led to a new willingness by the Soviets to negotiate arms control as well as “some help by both communist powers with the Vietnam peace negotiations,” among other breakthroughs.

Kissinger later wrote that after he and Zhou finally agreed on the communique, the Chinese leader remarked to him: “This will shake the world.”

FOREIGN POLICY

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.