Virtual tour project intended to raise awareness of the UN World Heritage site and encourage more tourism.

By

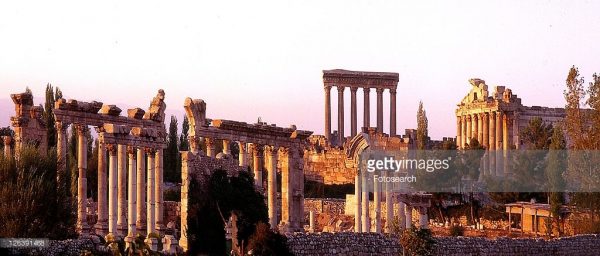

Beirut, Lebanon – Located in Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley, Baalbek – also known in antiquity as Heliopolis – is a UNESCO World Heritage site, home to some of the largest and most impressive Roman temple ruins in the world.

A newly launched virtual tour, Baalbek Reborn: Temples, offers visitors from around the world the opportunity to see these awesome feats of ancient architecture and engineering, not only as they are today, but also as they would have been more than 2,000 years ago.

“There’s just something very special about the place,” Henning Burwitz, a building historian and architect with the German Archaeological Institute (DAI), told Al Jazeera.

“It’s scientifically an extremely interesting place, being one of the more eastern Roman cities and sanctuaries. It’s quite a statement to build something like this in such a remote part of the Roman Empire.”

Between the global COVID-19 pandemic and numerous internal crises, Lebanon’s economy – already largely dependent on new US dollars brought in by remittances, international tourists and foreign investors – has suffered greatly.

Rather than replace real-world tourism, Baalbek Reborn: Temples is intended to raise awareness around the world of this unique world heritage site and encourage more tourism to Lebanon in general.

Created through a collaboration between the German Archaeological Institute (DAI), the General Directorate of Antiquities of Lebanon (DGA), the Lebanese Ministry of Culture, and US-based company Flyover Zone, this free virtual tour combines cutting-edge technology with the results of decades of archaeological research that is still ongoing.

The project used computer-aided design software such as AutoCAD and 3D Studio Max for 3D modelling, combing them with blueprint drawings provided by the DAI, along with 8K resolution panoramic photography from the ground and drone footage from above. Flyover Zone’s team then use a programme called Unity to integrate all these elements into their virtual simulation.

For Flyover Zone’s founder and president, Bernard Frischer, this project has been a dream come true. Within hours of its launch, the virtual tour had already surpassed 10,000 downloads.

“My day job still is that I’m a professor of informatics, and my branch of informatics is computing applied to cultural heritage,” he explained. “We started this company a few years ago to create virtual reconstructions of the most important cultural heritage sites around the world [using] 3D digital technology to visualize the latest scientific results, making it possible for the general public to take virtual trips through space and time.”

Within the app, users will be able to explore a series of 38 fully interactive, 360-degree panoramas, allowing them to investigate whatever might happen to catch their eye,

At the press of a button, a virtual tablet provided as part of the tour will provide text descriptions of locations, additional images, and an audio slider that controls the playback of a full audio-commentary soundtrack, produced in tandem with experts from the DAI and available in Arabic, English, French and German.

“The representation you can see will be tailored to the content of the commentary,” explained Burwitz. “If we explain the site today, you will see it as it looks today but if we talk about what it looked like in 215, the image will switch automatically to take you on a time travel to the year 215 and to show you what it looked like in antiquity.”

Frischer said there is “no point in doing this sort of reconstruction if it’s fanciful or artistic”.

“Yes, it should look beautiful and artistic in that sense, but if it’s only fanciful then it has no value, at least for academic purposes. The only way to make the model have value is to collaborate with the world’s experts who’ve been working on these monuments and really know all the details of what they looked like. So for Baalbek that would be the DAI, and thank God they agreed to help us.”

The DAI, a research institute in the field of archaeology under the federal foreign office of Germany, has been actively involved with the historical investigation of Baalbek’s temples and the surrounding area for more than 20 years, continuing a tradition of German-Lebanese archaeological cooperation that goes back centuries.

Some sites, such as the Temple of Bacchus, have been remarkably well-preserved and are still standing today. Others have almost completely disappeared, leaving behind only scant but nonetheless impressive remains, such as the six remaining rose granite columns – each more than 20 metres (66 feet) high and about 2 metres (6.5 feet) in diameter – that once framed the now absent Temple of Jupiter.

“Our part was to make sure the correct scientific bases were chosen,” said Burwitz. “We can see in the reconstruction the full extent of this marvellous building. We want you to feel like being on-site.”

Frischer said for a real sense of presence, nothing beats a virtual reality headset while on the tour.

“On the other hand, let’s say you move around a lot and even maybe you’re going to travel to Baalbek; putting it on your smartphone is a good way to go. Of course, it’s free so you don’t have to choose,” he said.

The tour is available online and free of charge thanks to funding provided by Bassam Alghanim, a retired Kuwaiti banker and archaeology enthusiast who financed the project in memory of his parents, Yusuf and Ilham Alghanim.

Baalbek Reborn: Temples will also be used to promote another joint project between the DGA and Lebanese NGO arcenciel, which will provide vocational training courses teaching heritage crafting skills, with a goal of creating a skilled workforce of young artisans who will support further restoration projects in Beirut.

“We wanted to take advantage of this launch and all the attendant publicity to help Lebanon – particularly Beirut – to recover from the terrible explosion of August 4,” said Frischer. “We had a great collaboration with the ministry of culture [and we] wanted to give something back by tying our initiative to this charitable initiative.”

ALJAZEERA

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.