By CHARLES LISTER

While the world wasn’t watching, Syria has edged toward collapse, and the dictator is in his weakest position ever. The U.S. now has a narrow chance to prevent a catastrophe. At least 85 percent of Syrians live in poverty and the regime has failed to acquire sufficient wheat supplies for the remainder of 2020—meaning bread shortages are only a matter of time. Some in the nongovernmental organization sector are quietly warning of a famine. There is virtually nothing that Assad’s two primary allies, Russia and Iran, can or will do economically to leverage Syria out of this crisis.

“We promised to keep things peaceful … but if you want bullets, you shall have them.”

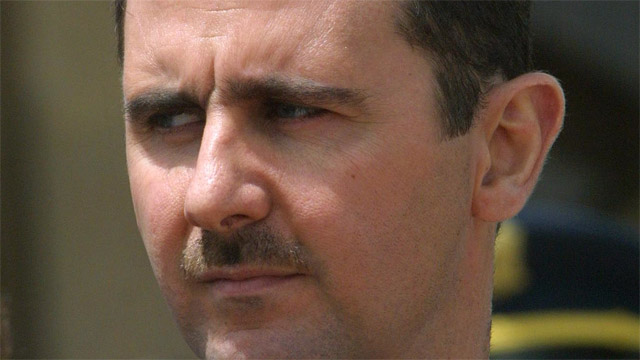

That was the wording of a message issued to Bashar Assad by the Druze community in Syria’s southern Suwayda province on Tuesday after three days of intensifying protests. Since then, its opposition to the Assad regime has only heated up, despite a pro-regime counterprotest on Wednesday, in which local state employees were threatened by secret police should they not participate. Demonstrators took to the streets against Assad again on Wednesday and Thursday, some bearing flags of the Syrian revolution.

Until recently, the Druze, a minority sect, had largely stayed out of Syria’s bitter nine years of conflict, but the nation’s spiraling economic crisis has forced them onto the street. Addressing Assad directly, protesters chanted “curse your soul, we are coming for you,” and expressed their solidarity with the 3 million-strong opposition community in Idlib, the last holdout of the armed rebellion against Assad.

As remarkable as they are, the protests unfolding in Suwayda are merely a symptom of a far greater crisis striking at the heart of the Assad regime and its prospects for survival. Assad’s decision to sack his prime minister, Imad Khamis, on Thursday was a clear indication that economic collapse and newly vocal opposition posed a real challenge to his legitimacy.

For some time, it has become commonplace to declare Assad the victor of the war in Syria—a dictator who managed to survive nearly a decade of rebellion and civil war by brutally suppressing dissent and exploiting the support of Russia and Iran to keep his grip on a burning country.

But that has never been an accurate way to see Syria. Assad may have crushed the opposition to his dictatorial rule in 60 percent of the country, but in 2020, every single root cause of the 2011 uprising is not just still in place, but has worsened. Challenges to the regime’s prosperity, credibility or survival remain in place in every corner of the country. For the first time in nearly a decade, the millions of Syrians who outwardly support Assad or who have remained quietly loyal to his rule have begun to share whispers of their own exasperation. For most, life in 2020 is a great deal worse than life at the peak of nationwide armed conflict in 2014-15. In holding on to power, Assad has effectively—and purposely—destroyed his own nation and economy.

This new and almost unprecedented moment offers America an opportunity. Although it may seem like the Trump administration—and particularly the White House—has paid little attention to Syria, it has an opening now. If it uses its remaining levers to exploit Assad’s newly vulnerable position within an energized diplomatic effort, in concert with our many allies in Europe, the Middle East and elsewhere, it has a chance to usher in real and long-overdue changes to a country that could otherwise become a global tinderbox.

For now, taking all current circumstances into account, three scenarios appear to be on the horizon. On the one hand, Assad could take Syria down the North Korea route, isolating the nation from the global economy, consolidating its status as a global pariah, and attempting to unify his loyalist population with a sense of solidarity in victimhood. In many ways, Assad has prepared his loyalist base, particularly Syria’s many minority communities, for this very scenario over the past nine years of conflict, though the extent to which a genuine and unshakable cult of personality has been built around his rule is open to question.

Syria could also take a truly unprecedented turn for the worse, crashing into a debilitating crisis that tears every fiber of the country apart and, as hard as it is to imagine in 2020, leaving even greater levels of destitution, famine, and worsening criminality and predatory behavior. In this scenario, loyalist unity would dissolve altogether, leaving in its wake a Somalia-type failed state that’s both a human-rights disaster and a breeding ground for dangerous extremists and regional instability.

Or finally, as several longtime loyalists have suggested to me in private in recent days, this extraordinary internal crisis could spark a change at the top. In their eyes, this moment may already represent a greater threat to Assad’s survival in power than the one posed by the opposition at its peak in years past. In this scenario, the Assad path for Syria may emerge as so deeply distasteful for so many Syrians that instability, anger, disenchantment and perhaps a Russian push might end up unseating him for another established regime name.

Those scenarios are a lot to swallow, but there may be another one in which the United States could play a meaningful role alongside its many allies, in Europe and the Middle East itself.

The situation in Syria is already of grave concern to Russia, which along with Iran is the primary source of Assad’s external support. In Moscow, rhetoric critical of Assad—both in public and private—has never been more acute. The rapid and likely irreversible decline of Syria into an economic basket case, combined by a continued and aggressive policy of isolation from the international community, could end up triggering—if it hasn’t already—a deep sense of unease in Russia and Iran, leaving them vulnerable and potentially open to considering some form of international settlement, conditioned on gradual reengagement and sanctions easing.

American leverage in Syria may have suffered from irrational and unpredictable decision-making from a Trump Oval Office, but the U.S. still matters in the region and the world at large, and has a chance to shape the outcome. In fact, Assad’s current weakness provides more meaningful opportunities than we have seen for some time.

In recent months, Syria’s economy has collapsed, resulting in hyperinflation, mass business closures, widespread food shortages and increasing unemployment. With the Syrian pound floating between 2,400-3,000 to a single U.S. dollar, an average monthly salary in Syria now buys roughly one watermelon, or two pounds of lemons. At least 85 percent of Syrians live in poverty and the regime has failed to acquire sufficient wheat supplies for the remainder of 2020—meaning bread shortages are only a matter of time. Some in the nongovernmental organization sector are quietly warning of a famine that may set in later this year or in 2021. And still hovering over all of this, Covid-19 cases continue their slow rise.

Meanwhile, Turkey’s recent decision to transition the economy of northern Aleppo—a region it controls militarily, alongside Syrian opposition proxies—to the Turkish lira has removed roughly 10 percent of Syria’s population from the Syrian pound, and plans are reportedly afoot to do the same in Idlib, where an additional 18 percent of Syrians now reside. The departure of nearly a third of Syrians from their national currency may prove to be the nail in the coffin for Syria’s economy. There is virtually nothing that Assad’s two primary allies, Russia and Iran, can or will do economically to leverage Syria out of this crisis.

As he has strained for much-needed capital, Assad has opened chaotic new fronts in his own domestic politics. Most notably, he has unleashed the dogs on his cousin, longtime friend and Syria’s wealthiest businessman, Alawite billionaire Rami Makhlouf, whose money had arguably done more to keep the regime afloat over the past nine years than any other Syrian actor. A coordinated effort enforced by Syrian intelligence services has seized Makhlouf’s most prized assets—including Syria’s principal cellphone network, SyriaTel, whose services Makhlouf had allegedly provided free of charge to Syria’s military and intelligence services—and placed him under house arrest. But Makhlouf has not gone quietly, releasing multiple Facebook videos decrying the regime’s betrayal and criminality, and the spat has engendered a sense of unease within Syria’s business community. He is unlikely to be the last target of Assad’s thirst for power, particularly as he grasps for air amid Syria’s financial collapse.

At this point, it’s important to note that Syria’s economic crisis is not the consequence of the wide spectrum of sanctions imposed by the U.S. and Europe, principally against individuals and business entities judged to have been involved in war crimes, though under some circumstances sanctions have exacerbated the effects of the decline. Instead, Syria has suffered principally from the financial crisis next door in Lebanon, as well as from the crippling levels of corruption and incompetence that riddle the regime and wider government structures. Despite regaining the military advantage back in 2018, Assad has also stubbornly insisted on prioritizing costly—and brutal—military campaigns against his own citizens in Idlib, where a million people were displaced late in 2019.

Beyond the economic sphere, the Assad regime’s failure to stabilize former opposition areas and its continued brutal and corrupt practices are driving intensifying instability. In addition to the uprising in Suwayda, the “cradle of the revolution” in Deraa has witnessed an expanding armed insurgency responsible for hundreds of attacks and hundreds of deaths in the last year. ISIS is now resurgent in the regime-controlled central desert, and Turkey has doubled down in defending what remains of opposition territory in the northwest, briefly unleashing an unprecedented air campaign against the Syrian military in March. Meanwhile, Israel continues to make a mockery of Syria’s sovereignty in striking Iranian targets at will and Turkey is almost certainly consolidating a permanent presence in northern Aleppo.

There is no magic solution to Syria’s many problems, and if there were one, the U.S. would not be in a position to provide it. However, Syria doesmatter to U.S. national security and interests in the Middle East and beyond. The extraordinary list of destabilizing effects that have stemmed from Syria’s crisis and transformed the world in the past decade are palpable evidence of Syria’s importance. Its mass migrant flows to Europe precipitated a surge in populism and far-right politics around the world, along with Brexit and the weakening of the European Union. The explosive rise of ISIS, and the massive international military response, was a consequence of Syria’s civil war. It’s not too much to say that Trump’s dramatic election in 2016 may, in part, have been enabled by the chaos in Syria.

With his long list of war crimes, including more than 350 chemical weapons attacks, Assad has degraded international norms unlike no other actor in modern history. Russia has defiantly returned to the Middle East, pulling NATO’s second- largest standing army (Turkey) virtually out of the alliance and undermining U.S. influence and credibility regionwide. Iran has capitalized on Syria’s problems to achieve its decades-old regional goal of establishing an arc of influence from Tehran to Beirut and Palestine, effectively resetting regional power dynamics. And lastly, the world’s muffled response to Assad’s record-setting list of war crimes, as well as the 700,000 dead and nearly 12 million displaced, appears to have inspired an era of international isolationism in which dictators are likely to thrive.

America will always have an interest in helping solve Syria’s crises, but rarely will we have a chance like the one currently in play. Though it has shrunk in scale, our military presence in eastern Syria, where we help control roughly 25 percent of the country and the majority of Syria’s oil resources, provides us with a meaningful place at the table, as do the many other levers of influence resulting from our diplomatic clout and the combined pressures resulting from American and European sanctions. Syria’s only way out of this newly intensified crisis may be revealed when the gates to international diplomacy and economic reengagement are opened, but we are holding those gates firmly closed today.

The lock on the gates will grow a great deal harder to crack when in a matter of days, the most significant sanctions regime ever imposed on Syria—the Caesar Act—will come into force, forbidding any economic engagement with the Assad regime by any actor worldwide, ally or foe. That is a significant and conveniently timely step, but what is mysteriously missing is a serious diplomatic track of action, in which the U.S. seeks to take advantage of what may be the Assad regime’s weakest period in nine years.

The State Department has been engaging behind the scenes with Moscow in recent weeks, consulting on the feasibility of a new Syrian diplomatic process, and this is prime time to put that on the table. Though Russia has done a great deal in Syria on the cheap, brutally subduing the Syrian opposition and repeatedly outbluffing the international community in a game of high-stakes poker, the Kremlin cannot afford to be left with what appears to be in the cards today in Syria. The ultimatum from Washington ought to be simple: The economic isolation of Assad’s regime is easy to sustain and deeply costly and dangerous to you, but it can be eased in return for meaningful political concessions from Damascus. A genuine political process leading to some form of power sharing, nationwide ceasefire, the release of thousands of political prisoners, constitutional reform, an acceptance of decentralization and internationally monitored elections inclusive of Syria’s regionally displaced, to name only a few.

Though back channels with Moscow and dialogue with Europe is good, it is far from enough. Washington has every interest in getting the diplomatic ball rolling, now. If we fail to assertively act in concert with our allies at this opportune moment, we will live to regret it.

Charles Lister is a senior fellow and the director of the Syria and Countering Terrorism and Extremism programs at the Middle East Institute and author of The Syrian Jihad: Al-Qaeda, the Islamic State and the Evolution of an Insurgency.

(POLITICO)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.