Hezbollah has been working for years on integrating itself into the Lebanese state. Now that the country is falling apart, Hezbollah’s assimilation into the state apparatus, which was initially meant to protect the organization against international pressure, could pose a direct threat to the group’s future.

Lebanon is facing a host of fresh challenges, from an economic collapse marred by a financial crisis to the coronavirus pandemic. While the mismanagement of these various emergencies cannot be blamed solely on one Lebanese faction alone, Hezbollah has undoubtedly contributed to the country’s downfall. The militant group’s use of the state to fend-off international sanctions and shape foreign policy has acted as a double-edged sword, making the pushback on Hezbollah a deadly one for Lebanon.

Hezbollah’s reliance on corrupt political figures—to achieve dominance and parasitize the state—has also severely hurt the group’s credibility, particularly in the wake of the massive economic crisis.

Traditionally, Hezbollah members have shied away from sensitive government positions, with its ministers handling agriculture, youth, industry, and more recently, health. Despite its political caution, the group has direct influence on essential institutions from security to foreign policy.

Hezbollah controls foreign policy

Hezbollah’s indirect control over foreign policy has been guaranteed with the appointment of allied figures from the Christian Free Patriotic movement (FPM), headed first by President Michel Aoun and more recently Gebran Bassil since 2015. During his tenure as a foreign minister from 2014 to 2020, Bassil repeatedly took regional stances detrimental to Lebanon, despite the adoption by the government of a regional self-distancing policy. In 2018, Lebanon’s foreign minister failed to attend an extraordinary Arab League meeting on March 22 to discuss “violations” committed by Iran. Beirut’s failure to condemn attacks on Saudi diplomatic missions in Tehran also led to the suspension in 2016 of a $3 billion aid package for the Lebanese army.

Arab heads of state snubbed Lebanon during the 2019 Arab Economic and Social Development Summit, held in Beirut, as Hezbollah and the Amal movement—a Shia political party and Hezbollah’s ally—insisted Damascus should attend the conference.

Hezbollah’s foreign ventures across Lebanon’s borders has angered Arab leaders and the country’s former allies. In Syria, Hezbollah has been supporting the regime of President Bashar al-Assad, leading troops into battles, and training the army and loyalist factions. In Yemen, Hezbollah has provided technical support to the Iran-backed Houthi rebels, pitting it against the internationally-recognized government backed by Saudi Arabia. Adding insult to injury, Hassan Nasrallah, Hezbollah’s general secretary, also repeatedly threatened Saudi Arabia, labelling it as “house made of glass,” as tensions escalated in the Persian Gulf. Hezbollah’s antagonistic regional policies made new enemies this year as dozens of Hezbollah fighters were killed during Turkey’s operations in Syria’s Idlib province.

As a result, Lebanon’s standing has been severely hurt at the regional level. When former Prime Minister Saad Hariri attempted to drum up financial support for Lebanon from Arab leaders during 2019, he came back empty-handed.

Lebanon’s banking sector, already in tatters, is the indirect victim of the war on Hezbollah, which is under heavy US sanctions.

A hostage of political alliances

Internally Hezbollah is a hostage of its political alliances. In October 2019, when daily protests shook Lebanon, much of the anger of demonstrators was directed against Hezbollah’s main allies: Foreign Minister Bassil and House Speaker Nabih Berry, head of the Amal movement, who were both accused of corruption.

At the time when he was energy minister in 2011, Bassil hatched a $5 billion dollar plan that would provide twenty-four-hour electricity for the first time since the civil war and make Lebanon a net energy exporter by 2018, an effort to combat years of outages due to an inefficient and corrupt energy sector. Anti-corruption demonstrators have hurled repeated insults at Berry, allegedly involved in many scandals. Despite corruption allegations, Hezbollah’s alliance with Bassil’s FPM and Amal remains solid, as both parties have allowed the movement respectively to avoid accusations of sectarian monopolization of the political system, which is rejected by Lebanon’s multi-communitarianism, and consolidate power within its own community.

The battle against corruption is nonetheless essential for Lebanon’s future, as it remains the main culprit behind Lebanon’s soaring debt. In March, the Lebanese government made the decision to default to protect its dwindling foreign currency reserves, estimated at around $35.8 billion, according to figures provided by the Byblos Bank to the author. Lebanon needs its foreign currency reserves to finance imports including food, medication, and construction materials amounting yearly at around $20 billion.

Experts believe that the economy will now significantly contract. Nassib Ghobril, a chief economist at Byblos Bank, told this author that the recession, estimated at 4 percent during 2019, will reach double-digit figures. Inflation, which was estimated at 10 percent for January is also expected to double—reaching around 20 percent—with people losing at least 50 percent of their purchasing power in the long run. Unemployment is also on the rise, with over 200,000 people having lost their job in 2019 alone. Experts believe the situation will further worsen as the coronavirus pandemic has hit Lebanon. The country is now under lockdown.

What this means for Hezbollah’s future

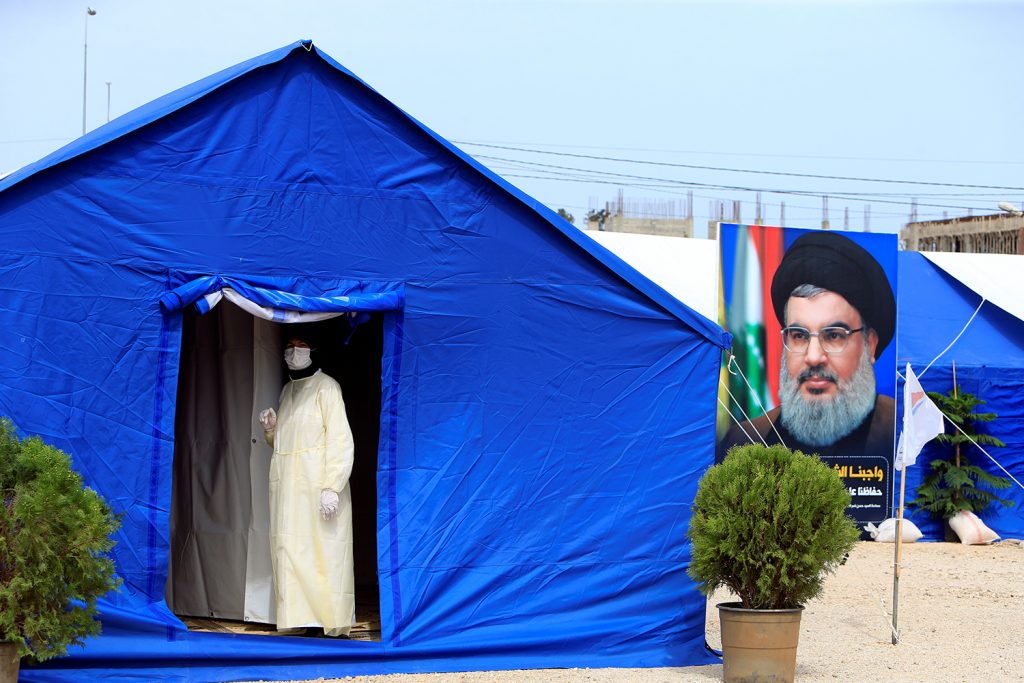

This is all very bad news for Hezbollah. The party is increasingly reliant on the state to make up for Iran’s dwindling financial support. Hezbollah also depends on the health ministry to treat its injured and its supporter base. Additionally, control over Lebanon’s borders allows Hezbollah to engage in a number of smuggling activities—including food, petrol, and drugs—and counterfeiting money, sources close to the fighters told this author.

Hezbollah’s survival is thus closely linked to that of Lebanon, and its decline is ultimately its own. Ironically, the party is forced to maintain a belligerent foreign policy that is aligned with that of Iran, at the expense of its country. On a local level, it is the hostage of discredited allies. Both are running the country into oblivion. Despite its unquestionable military dominance, the party’s future is rooted to the well-being of its wider popular base and its unconditional support. As the 20th anniversary of the Israeli occupation nears in May, both are in question, as not much is left of Lebanon.

Mona Alami is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Middle East programs.

ATLANTIC COUNCIL

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.