by: Andrew Jefford

by: Andrew Jefford

The fact that most of Europe’s greatest wines are grown and made north of Madrid and Naples means that wine producers in countries such as Turkey, Lebanon and Israel face a credibility gap. Surely, drinkers wonder, it is simply too hot to produce good wine that far south?

The tempered warmth that underlies great wine production can be achieved in two ways. Latitude is certainly one, but altitude is another. Most of the grapes for the eight million bottles of wine Lebanon produces annually come from the Bekaa Valley — and the valley floor (often called a plateau) lies at about 1,000 metres above sea level, while the mountains that lie to each side crest 3,000 metres. That means cold winters, and cool nights in summer when the temperature can drop 20C or more after hot days. In any case, wine is commonly produced at such latitudes in the southern hemisphere. Australia’s Margaret River wine region lies at a similar latitude to Zahlé, Bekaa’s capital, the raw heat buffered in Western Australia not by altitude but by wide ocean spaces. Argentina produces ambitious wines at lower latitudes and higher altitudes still.

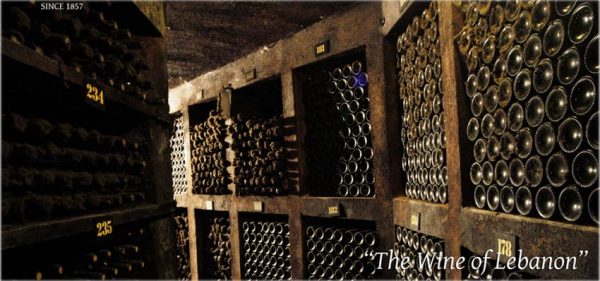

Exactly how long wine has been produced in the Bekaa is opaque, but the fact that the Roman emperor Antoninus Pius commissioned the enormous Temple of Bacchus for Baalbek (then Heliopolis) in the mid-second century suggests a long association. The Old Testament very nearly furnished a tasting note when Hosea, who lived in the eighth century BC, alluded (with prophetic vagueness) to the wine of Lebanon as a desirable commodity — of noted scent, according to the King James Version translation (14:7). A sweet scent and a suffusing sweetness of flavour remain the hallmarks of Lebanon’s finest red wines. At the same time, they have an almost improbable ability to age well, doubtless connected to the prolific though soft tannins that substitute in the Bekaa for the acidity more typical of serious red wine grown at higher latitudes.

The latitude problem can be overcome — but there are others. “We are very unlucky with our neighbours,” sighs Elie Maamari of Château Ksara, which produces almost 40 per cent of Lebanon’s wine. “The only peaceful neighbour we have is the Mediterranean.” The travails of the late Serge Hochar of Château Musar during the 1975-1990 Lebanese civil war were widely reported. At times he had to resort to using boats to get grapes via sea from the Bekaa to the Hochar winery in north Beirut, and he came close to losing his life in Beirut shelling episodes and in check-point traumas. But his experiences were shared by many colleagues. Yves Morard, a French winemaker at Château Kefraya, was arrested by Israeli soldiers during the 1982-85 invasion and briefly jailed in Tel Aviv. He was released only after he passed an exam his captors had set him on wine production. Syria’s agonising civil war has piled new pressure on the stoical Lebanese: more than a million refugees have crossed into this small country (half the size of Wales), putting enormous pressure both on its infrastructure and on its ever-delicate political equilibrium. No winemaker, moreover, can sleep serenely at night with Isis strongholds less than 100km away, in the countryside around Damascus.

The long traditions of Lebanese winemaking and the affection it commands among those who have discovered it means that a number of significant outsiders have become involved. Bordelais Dominique Hébrard and the producers of Vieux Télégraphe in Châteauneuf-du-Pape, Daniel and Frédéric Brunier, are involved in Sami and Ramzi Ghosn’s Massaya. So, too, was Hubert de Boüard of Château Angélus — though he has now switched his consultative advice to Ixsir, another Lebanese winery in which Renault-Nissan’s chief Carlos Ghosn is a partner.

When I spoke to de Boüard in Lebanon, he stressed that by seeking vineyards in the hills above the Bekaa, Ixsir was able to make wines with the kind of freshness and elegance he was looking for. Brunier, who I met in Châteauneuf, was frank about the challenges of trying to make fine wine in Lebanon — and in particular about that search for lightness, and the impact that climate change was having there (a lack of winter snow and rain). Both, though, said they felt at home in Lebanon. “I’d only worry about the situation if my partners were worried about it,” said Brunier, “but they have wonderful capacities of resistance and resilience.”

I tasted widely during a recent visit to the Bekaa and am convinced that the key northern Bekaa villages are still a fine wine-producing location, whereas the higher hill sites have yet to make a convincing case. The Bekaa is best compared not with other European sites but with Australia’s Barossa Valley and Napa in the US, both also sources of sumptuously ripe winemaking fruit. The Bekaa shares Napa’s ample tannic structures, though these are almost completely absent in the Barossa, where acid correction is preferred as a means of achieving balance. It is perhaps hard for Lebanese producers, whose working conditions are trying in the extreme and whose resources are often limited, to match the poise, purity and finesse of Napa — though some, such as Domaine Wardy’s talented winemaker Diana Salameh, are beginning to come close. Napa and the Bekaa also share the fact that Cabernet Sauvignon is the best-performing grape (whereas Syrah or Shiraz takes the lead in the Barossa). Merlot, Cinsault, Syrah and Carignan provide the supporting cast in the Bekaa, and blends tend to give better results here than varietal wines.

I mentioned the perfumed sweetness of Bekaa wines, while its fruit characters (every bit as unforbidding as those of the Napa) often suggest exotic spice or incense, and are thus hard not to call Byzantine. The sweetness can, on occasion, be overdone and using American oak, which has a sweeter character than French, to age the wines is a risky strategy. The best finish with an ample, creamy, melting softness, despite retaining their energy and their constitution admirably through time.

Some notable Lebanese wineries and their finest wines

Some notable Lebanese wineries and their finest wines

• Château Kefraya: Rosé, Comtesse de M (white), Comte de M, Ch Kefraya

• Château Ksara: Ch Ksara, Le Souverain

• Ixsir: Grande Réserve, El Ixsir

• Massaya: Terrasses de Baalbeck, Cap Est

• Château Musar: Hochar Père et Fils, Ch Musar

• Château St Thomas: Les Gourmets Rouge, Ch St Thomas, Merlot

• Domaine des Tourelles: Cinsault Vieilles Vignes, Domaine des Tourelles Rouge, Marquis de Beys, Syrah du Liban

• Château Wardy: Obeïdeh (white), Clos Blanc (white), Perle du Château (white), Cinsault, Les Cèdres, Les Terroirs

FINANCIAL TIMES

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.