BASHIQA, Iraq — When the Kurdish peshmerga commander arrived in this town in northern Iraq last month, he knew he was there to stay.

Col. Nabi Ahmed Mohammed’s force of 300 fighters had been tasked with securing Bashiqa as part of the Iraqi military’s offensive against the Islamic State in the nearby city of Mosul. The town had been home to minority Yazidis who were forced to flee when the militants arrived in 2014.

When Kurdish troops pressed into the town, they faced sniper fire and attacks from militants in underground tunnels. At least eight peshmerga were killed.

Now, Mohammed’s men are making plans for a permanent presence in the bombed-out town, long claimed by both the Kurds as part of their semiautonomous region and by the central government in Baghdad.

“We will fight for this place in the future against any enemy, whether it be Daesh or anyone else,” Mohammed said, using the Arabic acronym for the group. “Bashiqa is a good lesson for those who would think about occupying a Kurdish city, because none of them will survive.”

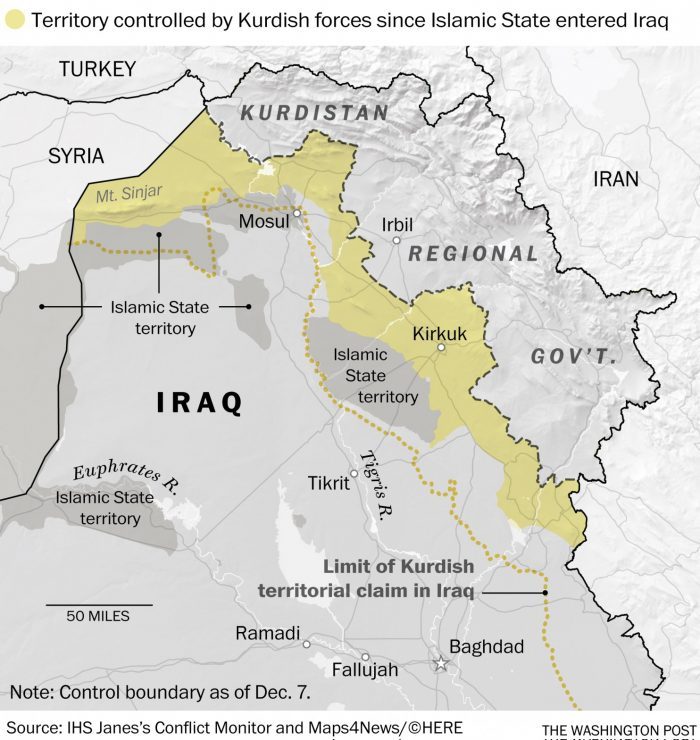

Kurdish intentions to remain in disputed areas of northern Iraq, despite warnings from Baghdad, threaten to spark renewed ethnic conflict once the Islamic State can be defeated, bringing long-standing feuds over land, oil and political power back to the fore.

The debate over the positioning of Kurdish forces after Mosul is retaken reflects larger questions about how groups that have formed uneasy alliances against the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria will interact after the imminent danger has receded.

The friction also illustrates the growing ambitions of minority Kurds across the Middle East, some of whom are seizing on the upheaval gripping the region to push for greater clout.

Fouad Hussein, a senior Kurdish official, said ties between Kurdish leaders and Baghdad have grown stronger since 2014, when peshmerga troops provided a needed defense against the Islamic State. Today, peshmerga fighters are supporting Arab troops from the Iraqi military around Mosul. Sometimes, they operate within sight of troops with whom they have clashed sporadically in the past.

Fouad Hussein, a senior Kurdish official, said ties between Kurdish leaders and Baghdad have grown stronger since 2014, when peshmerga troops provided a needed defense against the Islamic State. Today, peshmerga fighters are supporting Arab troops from the Iraqi military around Mosul. Sometimes, they operate within sight of troops with whom they have clashed sporadically in the past.

But Kurdish leaders remain wary about whether cooperation can be sustained. “The question is, the day after, how are we going to deal with each other?” he asked.

Iraqi Kurds have enjoyed relative autonomy in their northern region since 1991. After the 2003 U.S. invasion, Kurdish authorities took advantage of weak governance to expand their influence in areas such as Bashiqa, according to Denise Natali, an Iraq expert at the National Defense University.

Those areas make up a collection of disputed territories whose status remains unresolved despite years of international efforts to broker a compromise.

“There’s just tremendous potential for all kinds of conflict,” said Kenneth Pollack, a scholar at the Brookings Institution. “The extent to which external powers are so amped up over the future of these issues in Iraq, it makes it that much more explosive.”

Kurdish and Iraqi leaders remain far apart on other issues, including Kurdistan’s effort to establish itself as an independent oil player and allocations from the Iraqi budget.

Kurdish officials say missing budget payments from Baghdad have exacerbated an already dire economic situation. Public salaries have been slashed, adding to a political crisis that has prompted the region’s president to offer to resign.

As the battle unfolds in nearby Mosul, Iraqi Kurdish leaders insist they have a right to protect majority Kurdish areas that lie outside of their region’s official borders.

Masrour Barzani, chancellor of the Kurdistan Security Council, said Kurds, Yazidis and Christians in areas beyond where peshmerga are now positioned feel a primary loyalty to Kurdistan.

While most people in Iraqi Kurdistan consider Yazidis to be Kurds, Yazidis themselves are divided about that claim.

Bashiqa holds more than demographic importance. The town sits next to an oil field included in a deal that Kurdish authorities, in defiance of Baghdad, struck with ExxonMobil in 2011. Since 2015, Turkish troops have been stationed at a nearby military base, training local fighters against the Islamic State.

Barzani said areas retaken by peshmerga forces before the Mosul operation began will remain under Kurdistan’s control, and that is “not negotiable.”

Lt. Gen. Yahiya Rasoul, an Iraqi military spokesman, said plans drawn up before the offensive began on Oct. 17 stipulated that peshmerga would withdraw to areas it occupied before then, meaning they would not remain in Bashiqa or some other areas where Kurds have exerted influence in the past.

“We believe the peshmerga troops and the regional government are obliged to carry out the agreements that have been made,” he said.

Col. Halgurd Hikmat, a spokesman for the Ministry of Peshmerga, said no specific withdrawal plan had been made. When Mosul falls, he said, Kurdish and Iraqi officials will hold talks about peshmerga positions and who will administer Nineveh province.

Both sides cite an agreement the Pentagon struck with Kurdish authorities earlier this year as proof that the United States backs their plans. One U.S. official, speaking on the condition of anonymity to discuss a sensitive issue, said no specific locations were identified for peshmerga positions after Mosul.

On a cold, misty evening last week, Mohammed and his men warmed themselves around a fire outside his command center in Bashiqa.

The city has been largely flattened by airstrikes, many of the shops and homes a jumble of rubble and rebar. Residents have not yet returned, giving it the feel of a ghost town.

The colonel plans to remain in Bashiqa until residents return, and then move to the city’s outskirts. He said locals saw what happened in Mosul, where Iraqi troops surrendered the city to the Islamic State. “Without the presence of peshmerga in the city, Yazidi Kurds will never feel safe to come back,” he said.

If Kurdish troops stay in Bashiqa, it appears likely joint control will resume, with Kurdish forces providing security and authorities who report to Baghdad providing other services.

The fate of other areas, such as oil-rich Kirkuk, could be far more contentious than Bashiqa.

Natali said Kurdish leaders would need to cut deals with local and Baghdad authorities if they hoped to remain in disputed towns and villages.

“There’s no way the Kurds can go in there and say, ‘Tough, this is ours,’ and think there will not be repercussions,” she said.

WASHINGTON POST

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.