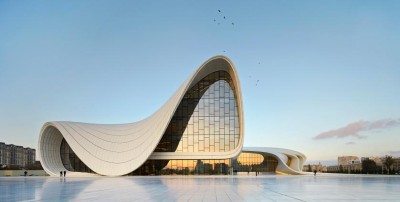

Hadid, 65, who had several close friends here and kept a pied-a-terre on the Beach, was close to seeing her Miami ambition realized: Her London-based firm’s 1000 Museum, a 60-story downtown condo tower on Biscayne Boulevard featuring a characteristically sinuous “exoskeleton,” has just reached nine stories in construction. Sections of the dramatic structural supports that will swoop to the top of the high-rise are now being installed.

Just three days ago, Hadid sent developer Greg Covin an excited note on the progress after driving and thanking him for taking her students from Yale — one of the many schools where the hyber-busy architect found time to teach — on a tour of the construction site.

Already, Covin said, onlookers can discern the boldly futuristic and technically innovative architectural complexity for which Hadid had been renown, and which he’s convinced will make the lavish 1000 Museum tower a Miami icon.

“She was really looking forward to seeing this building done,” Covin said, adding that all design work for it has been completed. “Later next year, when the tower is up and people can see the exoskeleton, they’re going to realize what a talent she was. There never has been a building like this.

“It was an honor to work with her and her team. I think she will go down as the greatest architect ever. But she was too young. She could have done a lot more.”

Hadid, the only female superstar architect in a field ruled by men, died early Thursday at Miami Beach’s Mt. Sinai Medical Center of what her firm said in a statement was a heart attack that struck while she was being treated for bronchitis.

Hadid, the only female superstar architect in a field ruled by men, died early Thursday at Miami Beach’s Mt. Sinai Medical Center of what her firm said in a statement was a heart attack that struck while she was being treated for bronchitis.

Friends and acquaintances say Hadid had been in Miami visiting, socializing and working, and had put in at least a few public appearances, including at a dinner celebrating the debut of Miami City Ballet’s production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream with sets designed by her friend, artist Michele Oka Doner, and at a lecture at the Perez Art Museum, which has an exhibit of Oka Doner’s work.

Hadid had been diagnosed with bronchitis but felt well enough to come out. She texted Oka Doner on Wednesday about meeting for dinner in early April because the illness prevented her from going back to London, the stunned artist said on Thursday from her loft in New York.

“She knew she had to deal with bronchitis, but there was no worry about anything else,” Oka Doner said.

Oka Doner met Hadid in the 1980s, when the architect had built little and had just four people working for her, and got to know her as Hadid battled to gain recognition as an architect “in a man’s world,” something the two spoke about frequently. But Oka Doner said that preoccupation seemed to recede as the blunt-spoken Hadid became the first woman to win the profession’s highest award, the Pritzker Prize, in 2004, and subsequently cemented her reputation as not just a great female architect, but as a great architect, period.

Hadid eventually transcended her role as an architect to become a model for women struggling to climb the ranks in other professions, and for women in the Arab world in particular, Oka Doner noted. Hadid was born and raised in Baghdad, then studied mathematics in Beirut before moving to London to study and train as an architect.

“It’s immeasurable what she did. Her legacy for women is so huge,” Oka Doner said. “As she stands in the field of architecture, so does she stands in the Middle East as to what the female mind and heart can do.”

Hadid and her now 400-person-strong firm, which includes her frequent design partner Patrick Schumacher, is responsible for major architectural landmarks around the globe, including the aquatic center at the 2012 London Olympics and BMW’s headquarters in Germany. She also had been at work on two other local projects.

One, a sleek, curvaceous design for a planned Miami Beach city garage near the ballet company’s headquarters, had stalled over construction cost estimates that ran well over the budgeted amount — an issue that dogged some of Hadid’s most prominent projects, including her firm’s design for the stadium for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, which was scrapped because of soaring projected costs. Beach officials have negotiated with Hadid since last year to bring the garage cost down, and commissioners are scheduled to get an update April 13.

Hadid had also crafted preliminary designs for developer Mario Garnero’s budding plan for a university in Miami Beach’s North Beach neighborhood. In a statement, Garnero said he hopes to continue working with Hadid’s firm on the proposal.

Hadid does have one completed Miami commission — the Elastika sculptural work that stretches across the atrium of the historic Moore Building in the Design District. Developer Craig Robins commissioned the piece in 2005, when Hadid won the designer of the year award from the Design Miami fair that he co-founded. The two became close friends.

Ever since, said Robins, the architect had been hankering to do a big project in Miami, a city she quickly adopted as a second home.

“She had a real connection with Miami,” Robins said, echoing others. “She loved the weather and the multicultural spirit of Miami. She felt at home here. She wanted to do something here because she just loved the city. It’s not as if she needed another commission.”

Hadid, who designed not only buildings but also furniture, shoes and even a yacht, and was known for a regal personality as dramatic as her architecture. Usually swaddled in avant-garde couture robes and sheaths, either in black or some shimmery opalescent material, she could dominate a room and intimidate critics and underlings alike. (So serious was Hadid about clothes and fashion as a design art that she kept all the outfits she had worn over the years stored in an archive, Oka Doner said.)

“She was very vigorous. She took no prisoners. She expected other people she worked with to meet that very high standard of throwing that rock as far out in the universe as you could,” Oka Doner said. “There’s no compromises, and that’s what she demanded from people around her.”

But that formidable, not to say forbidding, public and professional persona melted away in private with friends, with whom she was warm, playful and generous, Robins and Oka Doner said.

“If you were Zaha’s friend, you were part of her family,” Robins said.

That, Oka Doner said, was at least in part due to the influence Miami — so different from the strictures of her upbringing in Iraq and the Old World social and professional structures of London — had on Hadid.

“Miami was the yin to the yang of her work,” Oka Doner said. “She loved the openness, the big sky. She loved the sun. She loved the color. She loved the parties. I think Miami opened up a whole new world for her.

“She was really part of the community for 10 years,” she said. “It’s a great loss for Miami.”

Miami Herald

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.