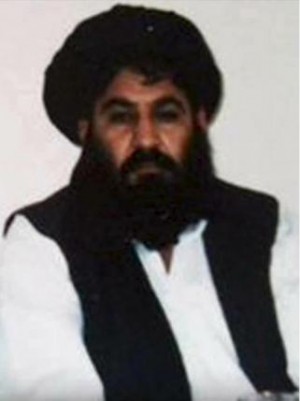

At the Taliban meeting this week where Mullah Akhtar Mohammad Mansour was named as the Islamist militant group’s new head, several senior figures in the movement, including the son and brother of late leader Mullah Omar, walked out in protest.

The display of dissent within the group’s secretive core is the clearest sign yet of the challenge Mansour faces in uniting a group already split over whether to pursue peace talks with the Afghan government and facing a new, external threat, Islamic State.

Rifts in the Taliban leadership could widen after confirmation this week of the death of elusive founder Omar.

Mansour, Omar’s longtime deputy who has been effectively in charge for years, favors talks to bring an end to more than 13 years of war. He recently sent a delegation to inaugural meetings with Afghan officials hosted by Pakistan, hailed as a breakthrough.

But Mansour, 50, has powerful rivals within the Taliban who oppose negotiations and have been pushing for Mullah Omar’s son Yaqoob to take over the movement.

Yaqoob and his uncle Abdul Manan, Omar’s younger brother, were among more than a dozen Taliban figures who walked out of Wednesday’s leadership meeting held in the western Pakistani city of Quetta, according to three people who were at the shura, or gathering.

“Actually, it wasn’t a Taliban Leadership Council meeting. Mansoor had invited only members of his group to pave the way for his election,” said one of the sources, a senior member of Taliban in Quetta. “And when Yaqoob and Manan noticed this, they left the meeting.”

Among those opposing Mansour’s leadership are Mullah Mohammad Rasool and Mullah Hasan Rahmani, two influential Taliban figures with their own power bases who back Yaqoob.

But Mansour got a boost late on Friday with the surprise backing of his longtime rival, battlefield commander Abdul Qayum Zakir, a former inmate of the U.S. prison in Cuba’s Guantanamo Bay.

In a letter published on the Taliban website, Zakir wrote that he had read reports “that I had differences with Mullah Akhtar Mohammad Mansour. Let me assure that this isn’t true”.

A Taliban commander close to Zakir, Nasrallah Akhund, confirmed by telephone that Zakir wrote the letter.

PEACE TALKS IN JEOPARDY

The leadership gathering was held outside Quetta, where many Taliban leaders have been based since their hardline regime in Afghanistan was toppled in a 2001 U.S.-led military intervention.

Afghan Taliban leaders have long had sanctuaries in Pakistan, even as Pakistani government officials have denied offering support in recent years.

Mansour leads the Taliban’s strongest faction and appears to control most of its spokesmen, websites and statements, said Graeme Smith, senior Afghanistan analyst for the think-tank International Crisis Group. But some intelligence officials estimate Mansour only directly controls about 40 percent of fighters in the field, he said.

That could make it difficult for him to deliver on any ceasefire that could emerge from future negotiations.

And Taliban insiders say that by sending a three-member delegation to meet Afghan officials in the Pakistani resort of Murree earlier in July, Mansour sparked new criticism.

Especially riled were members of the Taliban’s political office in Qatar, who insisted only they were empowered to negotiate.

“People … were not happy with Mullah Mansour when he agreed with Pakistan … to hold a meeting with Kabul,” said a Taliban commander based in Quetta. “The Qatar office wasn’t taken into confidence before taking such an important decision.”

The Quetta shura has sent a six-member team to Qatari capital Doha to meet with one of its leaders, Tayyab Agha, seeking his support for Mansour, according to another Taliban source close to the leadership.

RELATIONS WITH PAKISTAN

The divisions threaten a formal split in the Taliban. They also provide an opening to rival Islamic State (IS), the Middle East-based extremist movement that has attracted renegade Taliban commanders in both Afghanistan and Pakistan.

This month, two Afghan militant groups swore allegiance to Islamic State, and more could follow suit.

Despite threats both internal and external, Taliban fighters have been gaining territory in Afghanistan, where they are trying to topple the Western-backed government.

This week another district, this time in the south, fell to insurgents, who have exploited the absence of most NATO troops after they withdrew at the end of last year.

Opponents of Mansour criticize him for being too close to Pakistan’s military, which has long been accused of supporting the Afghan insurgency to maintain regional influence.

Pakistan has pushed Taliban leaders based in its territory hard to come to the negotiating table at the request of ally China and Afghan President Ashraf Ghani.

But many Taliban, and some Afghan officials, fear the recent talks are a ploy by Pakistan to retain control. The Pakistanis deny that.

Still, Mansour cannot afford to alienate Pakistan, said Saifullah Mahsud of the Islamabad-based FATA Research Centre. “No matter who is in charge of the Taliban in Afghanistan, they will have no choice but to have a good relationship with the Pakistani state. It’s a matter of survival,” he said. “I don’t think this agreement to go to the negotiating table is determined by personality; it’s more about the circumstances.”

Despite the opposition, Mansour retains a personal power base within the Taliban, and if he can keep the movement together it could lead to a new era for the insurgents.

Bette Dam, author of an upcoming biography of Mullah Omar, said the supreme leader’s absence paralyzed many Taliban officials.

Mansour could provide a more active focus for both the movement’s rank-and-file and those seeking to engage the Taliban.

“If he gets the credibility, it might not be such bad news to have Mansour replace the invisible Mullah Omar,” Dam said.

REUTERS EXCLUSIVE

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.