Emboldened as they mop up the last Islamic State forces in the city of Tikrit, Iraqi military leaders are already vowing to follow up that operation with a much more ambitious one: marching into the vast Sunni heartland in western Iraq to root out some of the most significant militant strongholds.

Emboldened as they mop up the last Islamic State forces in the city of Tikrit, Iraqi military leaders are already vowing to follow up that operation with a much more ambitious one: marching into the vast Sunni heartland in western Iraq to root out some of the most significant militant strongholds.

Iraqi and American officials say some progress in that region, Anbar Province, will be necessary before a serious effort is mounted to retake the northern city of Mosul from the Islamic State, also known as ISIS or ISIL.

But just how that can be accomplished is a source of concern. Despite boasts by the Shiite militias who took the lead in Tikrit that they were ready for Anbar, many Iraqi and American officials say it would be disastrous for a mostly Shiite-led force to begin assaulting towns in the Sunni-dominated area.

Anbar, after all, was the heart of the Sunni sectarian uprising against the American invasion and against the Shiite-dominated national government that followed. It was Al Qaeda’s original incubator in Iraq, and it was among the first places to fall to the Islamic State’s incursion.

The militants now hold more than half the province — including the city of Falluja and large areas around the capital, Ramadi. And they are ruthlessly trying to suppress a group of Sunni Arab tribes who are resisting them with the help of the Iraqi Army and some Shiite militias.

Still, Anbar tribal leaders who would be willing to work with the Iraqi government are adamantly opposed to more militias in Anbar, and want tribal forces to be armed and trained in their place.

One obstacle is that the Shiite-led Iraqi government has proved reluctant to arm the Sunni tribes more aggressively — as the Americans have tried to persuade it to do and are expected to encourage again when Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi visits Washington on April 14.

Mr. Abadi has publicly conceded the importance of getting more Sunni forces into the fight. On Friday, he met with political figures from Anbar Province, including Ahmed Abu Risha, a tribal leader whose brother was one of the critical leaders of the Sunni Awakening in Anbar Province, in which the tribes defeated Al Qaeda with American military help.

“Liberating Anbar Province will form an important gate to liberate the rest of the areas under the control of ISIS,” Mr. Abadi said.

Despite his military commanders’ tight timeline to begin an Anbar operation — some say it could start soon after Mr. Abadi’s return from Washington this month — it is still unclear where the manpower for the mission would come from.

Even with the use of large numbers of Shiite irregulars, along with Iranian military advisers, the conquest in Tikrit proved difficult, stalling for weeks until the advent of American airstrikes.

Relying heavily on those forces in Anbar would outrage the Sunni population there, American officials insist, and might further alienate people who are still on the fence about whether the Islamic State or the Shiite Iraqi government is the greater evil.

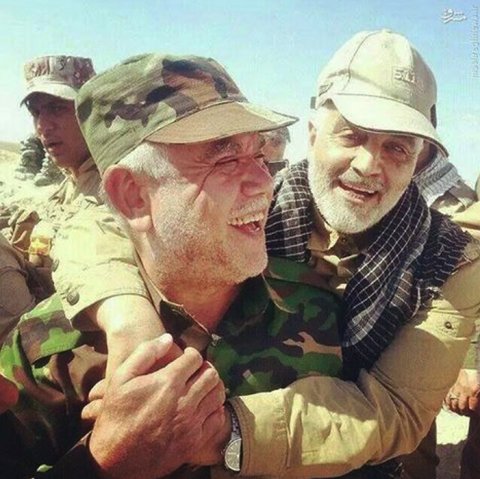

The Iraqi Army commander in Tikrit, Lt. Gen. Abdul al-Wahab al-Saadi, head of the counterterrorism force, said, “When I finish with Tikrit, I will go to Anbar, because I promised those people I would.”

Still, he conceded that it could not be with large numbers of Shiite militiamen — even though he is quick to credit them as an important part of recent Iraqi victories in Diyala and Salahuddin Provinces, including Tikrit.

“They were responsible for liberating 10,000 square kilometers of territory,” he said, or 3,861 square miles.

Replacing them in Anbar, for the most part, will be local Sunni tribes. But efforts to arm those tribes have moved slowly, as the Iraqi authorities remain suspicious that some might end up fighting against the Iraqi government or supporting the Islamic State.

There are also disputes among the tribes over which ones should get weapons, with some saying that the American military and Iraqi authorities are backing the wrong groups.

Sheikh Abdul Razak, a Jordan-based leader of the large Dulaimi tribe from Anbar Province, said that what he disparagingly calls “Baghdad sheikhs” had joined the government and would let Iranian-backed Shiite militias into Anbar to fight the Islamic State.

“It’s clear the popular mobilization is the hand of Iran, and this is going to be like ethnic cleansing of the Sunnis,” he said, referring to the militias by their official name, the Popular Mobilization Forces.

Mr. Razak even hired an American consultant, Jonathan S. Greenhill, to lobby Congress on his behalf and promote his view that the American-led coalition is picking the wrong partners in Anbar. Mr. Greenhill, of the Greenhill Group in Arlington, Va., is a retired Central Intelligence Agency officer whose biography lists him as former “chief of base in a Near East war zone.”

“The sheikh has deep support in Anbar and important valuable information on the terrorists,” Mr. Greenhill said, adding that his client has been unsuccessful in meeting with military officials from the coalition. “The coalition is dealing with the wrong sheikhs, who do not enjoy widespread Sunni support.”

Coalition officials insist that the Iraqi government will decide which tribes to arm and that any military aid to them must go through the government.

“This is their show,” said one senior coalition official, speaking on condition of anonymity as a matter of official policy. But, the official said, no one now seriously believes that Iranian-backed Shiite militias will be part of any major offensive in Anbar.

Unlike Anbar, the provinces of Salahuddin and Diyala, where the Shiite militias have been most active, have mixed Shiite and Sunni areas. In areas where Shiite militiamen were victorious, if there were populations of Sunnis, there were also reports of human rights abuses by the irregulars.

Such abuses — including extrajudicial killings of prisoners and looting by militiamen — are also being reported to a lesser degree in and around Tikrit, even though almost all of its population fled before the heaviest fighting.

Prime Minister Abadi publicly criticized the looting and ordered the militias to be withdrawn from Tikrit on Saturday as a result, a move that was widely praised by Sunni leaders.

On Tuesday, Mr. Abadi went a step further, ordering that all the popular mobilization forces be placed under the direct command of the prime minister’s office. The collective popular mobilization had been led by Hadi al-Amiri, a prominent Shiite politician and leader of the Badr Organization and militia, who has close ties to Iran.

“He tried his best to stop the looting in Tikrit, and we appreciate that, but he couldn’t,” Hamid al-Mutlaq, a Sunni member of Parliament from Anbar, said of the prime minister’s efforts. “The people of Anbar will not let that happen there.”

Hikmat Ayada, an adviser to Suhaib al-Rawi, the governor of Anbar, said officials expected an offensive to start there as soon as the prime minister returned from Washington. He said a final decision on starting the offensive had already been made in a meeting hosted by the American ambassador, Stuart E. Jones, the prime minister and other top Iraqi officials late last month, even before Tikrit fell.

“This will not be the same as in Salahuddin, in which the whole popular mobilization took part,” Mr. Ayada said. “Even if we have a few members of the popular mobilization, they are all under the leadership of the tribes or the army.”

Mr. Mutlaq and other Sunni leaders expressed doubt that the offensive would begin soon, largely because the process of arming Sunni tribes had gone so slowly. But he said the tribes were committed to ousting the Islamic State from Anbar.

“In the beginning, there were some people who supported ISIS in Anbar,” Mr. Mutlaq said, noting that many Sunnis had been angry at the former prime minister, Nuri Kamal al-Maliki. “Now, no one welcomes ISIS. The people of Anbar and Falluja are in a prison now, and they only want to get rid of ISIS.”

NY Times

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.