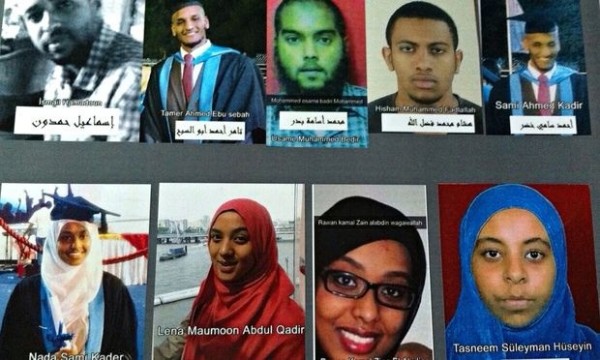

At first it seemed that another group of young Britons had slipped across the border to help Islamic State fighters consolidate and expand their caliphate. Yet the latest updates from the shifting frontline of the fiercely contested north Syrian border pose a problem for UK authorities. Can the Britons be classified as combatants? Are they terrorists? Have the nine British recruits to the barbarous regime even committed an offence?

Government counter-terrorism officials conceded that their apparent role as medics meant there was an apparent humanitarian aspect to the case. The source added: “It’s a difficult judgment to make, it really does depend on the nature of their involvement and whether that constitutes a form of terrorist activity.”

The Home Office said taking part in a conflict abroad could be an offence under criminal and anti-terrorism laws. It added that “fighting in a foreign war is not automatically an offence, but will depend on the nature of the conflict and the individual’s own activities”.

So a scenario in which people can travel to Syria, join Isis and return without prosecution does exist, but seemingly operates in favour of young British women. Police have been eager to distinguish girls who go to Syria to become jihadi wives and homemakers from men eager to take up arms.

A recent articulation of this came when the Metropolitan police head of counter-terrorism, Mark Rowley, told MPs on the home affairs committee that the three London schoolgirls who fled to Syria would not be prosecuted if they returned because there was no evidence they had committed any terrorist offence. Rowley said the trio were different from someone “running around in northern Iraq and Syria with Kalashnikovs” who later apologised for committing terrorist offences.

In other words, by the simple virtue of being medics, the students may be viewed by Scotland Yard as very distinct from the hundreds of British men who have previously crossed the Syrian border to join Isis. Intelligence experts, however, will also be acutely aware that this reading of the situation hide their true motives under the cloak of humanitarian work.

Some experts believe that the British medics should feel the full force of UK counter-terror legislation, arguing that offering medical assistance to wounded Isis fighters was as militarily effective as being an actual frontline soldier.

Shashank Joshi, senior research fellow at the Royal United Services Institute, said: “They appear to be providing material support which is just as combat effective as if they were providing direct assistance on the battlefield. They should be treated in the same way as if they belonged to a fighting unit.”

Yet it is pertinent to note that Britons have been freely allowed to give medical assistance to designated terror groups in the recent past, with Red Cross staff in Afghanistan teaching the Taliban basic first aid. This initiative was introduced in 2010, the deadliest year for British forces in the Afghan campaign, with 103 UK service personnel killed. Explaining its decision, the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) made reference to the Geneva conventions, which stipulate that medical care should be given to all people injured in a conflict, regardless of which side they are on.

The medical students, who are thought to be in the Syrian border town of Tel Abyad, could also potentially claim that they were abiding by the conventions’ internationally recognised treaties governing the humane treatment of soldiers rendered hors de combat, or incapable of fighting.

Crucially, the ICRC made the point that providing medical assistance to the Taliban was an opportunity to educate and civilise “non-state actors” – groups which are involved in a conflict but are not an official state and therefore not formally signed up to the Geneva conventions; groups like Isis.

How the medical students are treated if they attempt to return to the UK will certainly throw fresh scrutiny on what can often appear an incoherent approach by the UK authorities to those who have recently fought in northern Iraq and Syria.

Britons openly fighting on the same soil against Isis, often on behalf of Kurdish rebels – some linked to terrorist groups proscribed by Britain – are generally lauded. David Cameron insists there is a fundamental difference between fighting for the Kurds and fighting for Isis.

Others have travelled to Syria to fight for groups rebelling against President Assad, only to be arrested. The UK’s decision not to intervene in tackling Assad as thousands of civilians were murdered or targeted with chemical weapons was the catalyst for many Britons to travel to Syria, on what they saw as a humanitarian mission against a brutal regime.

Many have been arrested under counter-terrorism laws on their return to the UK, despite insisting they are not terrorists and are opposed to Isis. The medical students will hope that their humanitarian instincts are viewed very differently.

Turkish opposition politician Mehmet Ali Ediboglu, who is in regular contact with their families, said: “Let’s not forget about the fact that they are doctors, they went there to help, not to fight.”

Government sources suggest that, whatever happens now, it may take considerable time to ascertain the motives, movements and modus operandi of the students. It is also possible that the group may even retreat from frontline hospitals to Isis strongholds such as Raqqa, where Isis is accused of running a segregated health service, with hi-tech hospitals for fighters while the local populace struggles with basic medical amenities.

The Guardian

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.