The Islamic State’s horrific execution of a Jordanian fighter pilot by burning him to death set a new standard of savagery for the group and seemed likely to provoke Jordan into opening a new and possibly more volatile front in a war that already has unsettled the region.

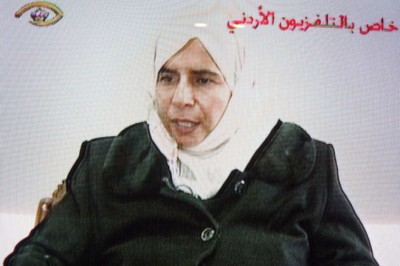

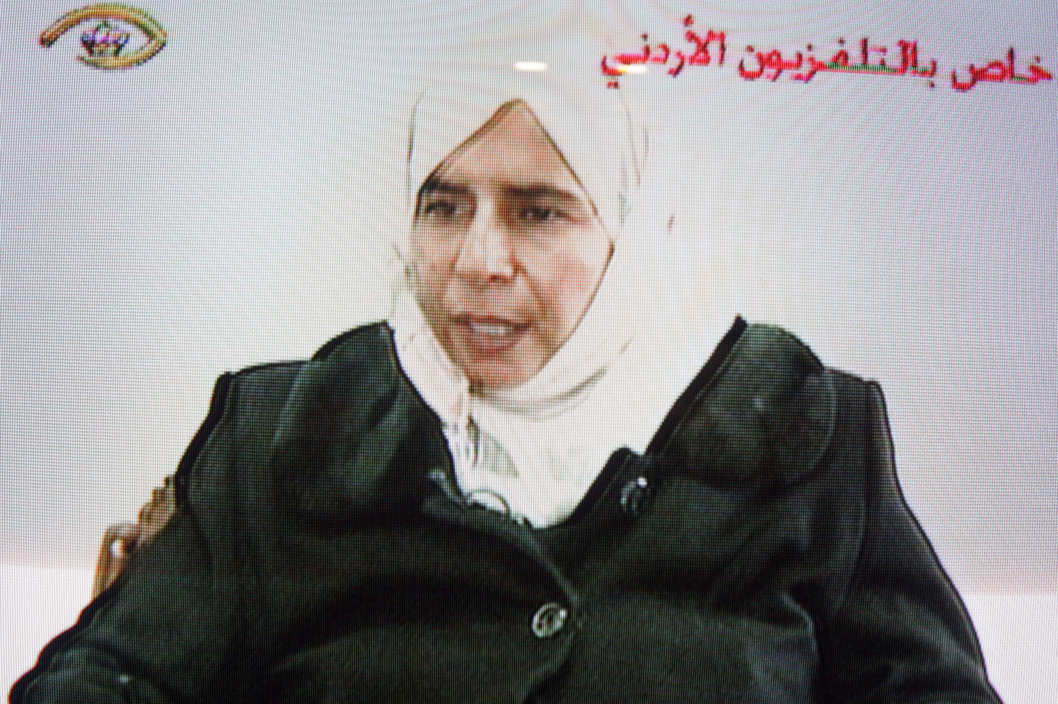

Within hours of the posting on the Internet of a video that showed 1st Lt. Moaz al Kasasbeh being led to a cage in the desert, doused with gasoline and set alight, Jordan moved quickly to take revenge, preparing to execute as many as six Islamic State-related prisoners, including a 44-year-old Iraqi woman whose freedom the jihadists had demanded last week.

The executions were carried out at dawn Wednesday, according to news reports from Amman, the Jordanian capital.

A government spokesman says Jordan executed 2 prisoners, hours after vowing a harsh response to the gruesome killing of a Jordanian pilot captured by the Islamic State extremist group.

Identities of the two executed prisoners in Jordanian hands were not immediately available, however initial reports indicate that the female prisoner Sajida al-Rishawi was one of the two executed. The second prisoner was a top aide to Al Zarqawi.

Before dawn, a convoy was seen leaving Juweideh prison where prisoner Sajida al-Rishawi had been held. The convoy arrived at Swaqa prison, where executions have been carried out.

“While the military forces mourn the martyr, they emphasize his blood will not be shed in vain. Our punishment and revenge will be as huge as the loss of the Jordanians,” Mamdouh al Ameri, a government spokesman, said in a statement read on Jordanian TV.

What other steps the Jordanian government might take were uncertain, but officials suggested that they would move rapidly to crack down on the group’s sympathizers and that other measures were likely, including stepping up the country’s role in the U.S.-led military coalition against the Islamic State.

The prospect of an all-out offensive against the Islamic State inside Jordan could prove unsettling to a country that has prided itself on remaining largely outside the line of fire in the region’s many wars. Even during the U.S. occupation of Iraq, when a Jordanian, Abu Musab al Zarqawi, founded al Qaida in Iraq to challenge the U.S. presence in that neighboring nation, Jordan remained largely free of violence, with the notable exception of a series of suicide bombings in 2005.

Al Qaida in Iraq was the precursor of the Islamic State, which now has designs to establish a caliphate that would stretch from Iraq to the Mediterranean and take in what is known as Greater Syria – which includes the modern nations of Syria, Lebanon, Israel and Jordan.

Several experts said that by burning the Jordanian pilot to death, the Islamic State was demonstrating a new level of barbarity intended to convey several messages – a more open hostility to the Jordanians, who in addition to participating in air raids on Islamic State targets in Syria have also encouraged anti-Islamic State activists to travel to Syria to fight; to reinforce its reputation as the globe’s most barbaric terrorist group; and to enhance its efforts to recruit sympathizers from across the world.

“To my mind, the key thing about this – in much the same way it was with the decapitations – is that they are telling everyone that they are the meanest, most brutal group on Earth and that message has resonated with potential recruits who view ISIS as the real deal,” said Daniel Benjamin, a former State Department counterterrorism coordinator and now the director of Dartmouth University’s John Sloan Dickey Center for International Understanding. “This is ISIS self-presentation at its grisly best.”

At 22 minutes the lengthiest execution video the Islamic State has yet produced, the video opened with Kasasbeh, dressed in the same orange jumpsuit as previous Islamic State victims, being led to a cage. Then a lone jihadi douses him with a liquid, presumably gasoline, from a jerry can as other militants look on. A trail of liquid is poured across the desert sand and ignited. The camera follows the flames as they near Kasasbeh, and the video remains focused on him as he burns, standing stoically, until his body crumbles into a heap.

Jordan state television said Tuesday night that Jordanian authorities believe Kasasbeh’s killing was filmed nearly a month ago, and that that was why the Islamic State refused to provide proof that Kasasbeh was still alive during recent negotiations. That belief was consistent with tweets from rebel activists opposed to the Syrian government who posted on Jan. 8 that the pilot had been executed.

Jordan’s King Abdullah and Foreign Minister Nasser Judeh were in Washington meeting with Secretary of State John Kerry just moments before the video was made public. There was no hint that any of the men knew of the death as they exchanged pleasantries during a signing ceremony marking increased U.S. assistance – from $660 million to $1 billion – to help Jordan cope with the Syrian refugee crisis and rising energy costs.

Immediately after the ceremony, however, the video hit the Internet, and statements of condemnation and condolences began flowing from the Obama administration to Jordan. The president called it “one more indication of the viciousness and barbarity of this organization.”

Islamist groups often behead captives who’ve been convicted, fairly or not, of dire crimes in an Islamic court, and beheading is a common form of execution in Saudi Arabia, which claims the Quran as its legal code and constitution. But burning alive is a rarity, and its religious foundation was uncertain.

Jihadist supporters on social media said the justification for burning comes from a Quranic verse that authorizes Muslims to “punish with an equivalent of that with which you were harmed,” according to several postings on Twitter and other forums.

Zaid Benjamin, a Radio Sawa journalist who monitors extremists online, noted that the same scripture was invoked after a mob set fire to the bodies of four American security contractors and strung up their charred corpses on a bridge in the Iraqi city of Fallujah in 2004. Today, Fallujah is part of Islamic State’s self-declared caliphate.

At the time, mainstream Muslim scholars condemned the act, saying that Islam does not allow for the desecration of corpses. The clerics also pointed out that the second part of the verse jihadists use as justification suggests that revenge isn’t the preferred reaction: “It is better for those who are patient,” the verse states.

The White House in a statement condemned the killing, even as it said U.S. authorities were attempting to verify the video. “We stand in solidarity with the government of Jordan and the Jordanian people,” the statement said.

President Barack Obama briefly addressed the killing during a forum on the Affordable Care Act at the White House. “This organization is only interested in death and destruction,” he said, referring to the Islamic State.

Kasasbeh’s execution is likely to raise tensions in Jordan, where his family had demanded the government engage in negotiations for his release in an increasingly bizarre series of demands and counter demands that included a $200 million ransom for two Japanese hostages who’ve since been executed and a demand for the release of Sajida al Rishawi, an Iraqi woman who’s been on Jordan’s death row since 2005 for her part in a series of bombings that killed at least 57 people in Amman.

The fate of Kasasbeh, whose plane crashed during a bombing run over Raqqa, Syria, in late December, had come to the fore only two weeks ago when one of the Japanese hostages, freelance journalist Kenji Goto, warned in an audio statement from the Islamic State that Kasasbeh would be killed if the Jordanians didn’t released Rishawi for Goto.

Jordan immediately expressed a willingness to swap Rishawi for Kasasbeh if evidence the pilot was still alive was provided, but the Islamic State counteroffer was that Rishawi be delivered by sundown last Thursday to an Islamic State-controlled border crossing with Turkey or both Goto and Kasasbeh would die.

Jordan continued to press for negotiations through both tribal channels and public statements, but on Saturday, a video of Goto being killed was posted on jihadist websites.

Kasasbeh’s fate was unknown until the release of the video on Tuesday evening local time.

The Islamic State, as far as is known, has never lied about the fate of the foreign captives it has executed, starting in August with the beheading of American journalist James Foley, and there was little reason to think the gruesome video was not an accurate representation of Kasasbeh’s death.

The video and Kasasbeh’s death is likely to deeply stress Jordan’s close-knit and tribal society. Kasasbeh’s family comes from a politically powerful tribe and had become unusually vocal advocates of a trade to keep their son alive.

Yousef Kasasbeh, the pilot’s father, had demanded the release of Rishawi, describing her as “nothing,” in exchange for his son’s life, but at no time did the Islamic State promise to release Kasasbeh, but rather only promised to kill him if the exchange for Goto failed.

AP

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.