Islamic State fighters were battling outgunned Kurdish fighters in the heart of Kobane on Thursday as the Pentagon warned that U.S. airstrikes alone will not save the Syrian border town from being overrun by the militants.

The fresh push came amid rising tensions between the Obama administration and Turkey, a NATO ally, over who should take responsibility for helping to save the town.

The Islamic State made gains overnight despite stepped-up American airstrikes over the past three days, and senior senior administration officials expressed growing exasperation with Turkey’s refusal to intervene, either with its own military or with direct assistance to Syrian Kurdish fighters battling the militants.

“Of course they could do more,” a senior official said. “They want the U.S. to come in and take care of the problem.” The administration would also like Turkey to be more zealous in preventing foreigners from transiting its territory to join the Syrian militants.

Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu countered on Thursday that a unilateral ground operation by Turkish troops also would not be enough to halt the militants’ advance.

“It is not realistic to expect Turkey to conduct a ground operation on its own,” Cavusoglu told a joint news conference in Ankara with visiting NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg. “We are holding talks. . . . Once there is a common decision, Turkey will not hold back from playing its part.”

He reiterated Turkey’s position that it is not prepared to step up efforts to help the U.S.-led coalition counter the Islamic State in Syria unless the removal of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad also becomes a goal of the operation.

“As long as Assad stays in power, bloodshed and massacres will continue,” he said. “The Assad regime is the cause of instability, and therefore a political change is necessary.”

In a sign of their reluctance to directly antagonize Turkey on the eve of a key diplomatic meeting, U.S. officials sent mixed signals on Ankara’s demand that the United States establish a protected buffer zone along Turkey’s border with Syria.

“It is not now on the table as a military option that we’re considering,” said Rear Adm. John F. Kirby, the Pentagon press secretary.

Separately, Secretary of State John F. Kerry said the idea of a buffer zone was “worth looking at very, very closely” and that it would be discussed when retired Gen. John Allen, coordinator of the U.S.-led coalition against Islamic State forces in Iraq and Syria, holds high-level meetings in Turkey on Thursday.

Britain and France, whose forces are conducting airstrikes against the militants in Iraq but not in Syria, also said they would not rule out a buffer zone.

French President François Hollande went further, saying after a telephone conversation with his Turkish counterpart that he supported the proposal made by President Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

In separate comments, a senior French official emphasized that Hollande had shared with Erdogan his “deep concern” over the situation in Kobane and indicated that Turkey itself is the country most directly positioned to do something about it. Several U.S. and European officials spoke on the condition of anonymity to go beyond public statements.

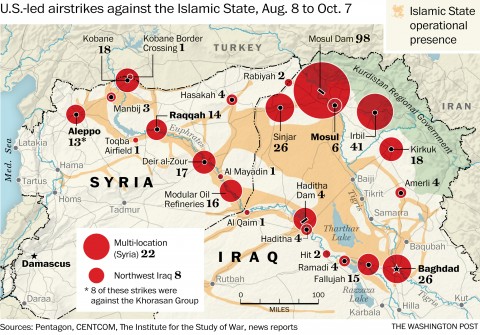

The intensified airstrikes against the Islamic State in and around Kobane, a total of 19 since Monday, appeared to be having some effect. For the first time in days, there was almost no shelling of the town, and Kurdish activists said the militants had withdrawn from all but a few streets on its eastern edge.

But Kobane remains surrounded on three sides by the Islamic State. On the fourth side, to the north, is Turkey, which positioned tanks, artillery and armored vehicles along the demarcation line with Syria to deter the militants from crossing into Turkey.

“Airstrikes are not going to save the town of Kobane. We know that,” Kirby said at a Pentagon briefing. “We all should be steeling ourselves for that eventuality.”

Kirby explained, with some apparent frustration, that the strategic goal of U.S. airstrikes in Syria is to destroy Islamic State infrastructure and prevent Syria’s use as a haven for operations in neighboring Iraq, not to save individual Syrian towns.

“There are going to continue to be villages and towns and cities that they take,” he said. “We all have to recognize that reality.”

The Pentagon considers the three days of strikes on militant positions around Kobane something of an interruption of its Syria campaign against Islamic State headquarters, oil refineries and command and control centers. The Kobane operation has been undertaken largely because the ground fight for the town’s survival has been broadcast live across the world from cameras just over the border in Turkey.

The Kurds say they do not want Turkish intervention but do want Turkey to permit weapons, ammunition and food to flow across its border to the 3,000 or so fighters defending the town.

Without fresh supplies, said Kurdish activist Ibrahim Kader, Kobane’s fall is only a matter of time. some estimates say tens of thousands of civilians are at risk in Kobane. A senior State Department official said that while exact numbers were difficult to obtain in a conflict zone, “our partners have indicated that the number of civilians in and around Kobane remains low” and that most needing protection had left for Turkey over the past several weeks.

The disconnect between U.S. and Turkish strategies is a reflection of differing goals — with the United States aiming to stop a terrorist threat and Turkey focusing on concerns that are much closer to home.

Turkey’s refusal to help the Syrian Kurds defending the town is based in part on the Turks’ long and convoluted history with the Kurdish Workers Party, the PKK, separatist militants in Turkey’s own Kurdish region. The PKK is affiliated with the Syrian Kurdish political movement whose military wing is defending Kobane.

Both Kurdish organizations are historically affiliated with Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, whose ouster is Turkey’s primary, long-term objective in Syria.

At a widely reported “secret” meeting in Ankara this week, Turkey set out three conditions for supporting the Kobane fighters — that they abandon Assad, dismantle the self-governing cantons they have established along Turkey’s border and pledge not to threaten that border.

“Ankara wants to see the PKK weaken in Syria so the organization comes to the bargaining table from a position of weakness,” said Soner Cagaptay of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy.

But Turkey has already seen considerable domestic backlash over its stance on Kobane. Protests erupted throughout the country’s Kurdish southeast this week on a scale not seen since the 1990s, with 19 people reported dead.

The issue of a buffer zone along the border has been repeatedly raised by Turkey since Syria’s civil war began in 2011.

The buffer zone was initially proposed to counter Assad’s own air attacks against U.S.-backed Syrian opposition forces, largely in the western part of Syria. Turkey and others proposed a “no-fly zone” in which patrolling U.S. aircraft would prevent Assad’s air force from attacking a protected area for opposition fighters and a corridor to funnel humanitarian aid to civilians.

The administration, with strenuous insistence from the Defense Department, consistently argued that Assad’s air defenses made it too risky, the resources required for constant air patrols were too great, and the strength and reliability of the opposition were questionable. Those arguments still apply, as Assad continues to bomb moderate opposition forces fighting in western Syria.

It was the rise of the Islamic State, in northern and eastern Syria, and its entry into neighboring Iraq, that provoked the U.S. air campaign, and destroying the Islamic State in both countries is the immediate U.S. objective. Assad is not bombing Islamic State positions, and the militants themselves have no air force, making a no-fly zone irrelevant to the U.S. goal.

Turkey believes that a U.S. fixation with the Islamic State has overtaken American interest in ousting Assad. The Turks have given no indication that they are prepared to participate in the coalition campaign in Syria unless Washington agrees to further the Turkish objective of removing the Syrian leader.

In a speech Tuesday, Erdogan spelled out Turkey’s conditions: the creation of both no-fly and buffer zones along its border with Syria — to protect the opposition rebels and to host more than 1.5 million Syrian refugees who have swarmed into Turkish towns — and training and arming the rebels. Obama has already said the U.S. military will begin a training program, which will take at least a year to put fighters in the field, and to step up its arms shipment.

“It’s all about keeping the removal of Assad as the priority,” Turkish political analyst Soli Ozul said.

Washington Post

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.