President Barack Obama will send 3,000 troops to West Africa to build treatment clinics and train health workers to try to halt the spread of the deadly Ebola virus, U.S. officials said on Tuesday, as the United States widens its response to the crisis.

President Barack Obama will send 3,000 troops to West Africa to build treatment clinics and train health workers to try to halt the spread of the deadly Ebola virus, U.S. officials said on Tuesday, as the United States widens its response to the crisis.

The U.S. plan, a dramatic increase from Washington’s initial response last week, won praise from aid workers and officials in the region. But health experts said it was still not enough to contain the epidemic, which is quickly growing and has caused local healthcare systems to buckle from the strain.

U.S. officials said the focus of the military deployment would be Liberia, a nation founded by freed American slaves that is the hardest hit of the countries affected by the crisis.

The worst Ebola outbreak since the disease was identified in 1976 has already killed nearly 2,500 people and is threatening to spread elsewhere in the continent.

A senior official with the U.N. World Health Organization said the Ebola outbreak requires a much faster response to contain its spread to tens of thousands of cases.

“We don’t know where the numbers are going on this,” WHO Assistant Director General Bruce Aylward told a news conference in Geneva, calling the crisis “unparalleled in modern times.”

Obama was set to formally announce the U.S. plan later on Tuesday during a visit to the federal Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta.

His plan calls for sending the 3,000 troops, including engineers and medical personnel, to build 17 treatment centres with 100 beds each, train thousands of healthcare workers and establish a military control centre for coordination of the relief effort, U.S. officials told reporters. The White House said the service members will not be responsible for direct patient care.

Obama’s announcement marks his second within a week of a new mission for the U.S. military, following last week’s speech outlining a broad escalation of the campaign against the Islamic State militant group in Iraq and Syria.

‘WELCOME NEWS’

Liberians hailed the word that U.S. troops were coming, recalling a previous military operation in 2003 that helped stabilise the country during a civil war.

“This is welcome news. This is what we expected from the U.S. a long time ago,” Anthony Mulbah, a student at the University of Monrovia, said in the dilapidated oceanfront capital. “The U.S. remains a strong partner to Liberia.”

In Liberia, a shortage of space in clinics for isolating victims means patients are being turned away, then infecting others.

The initial U.S. response last week had focused on providing funding and supplies, drawing criticism from aid workers for not deploying manpower as in other disasters like earthquakes.

White House spokesman Josh Earnest told reporters travelling with Obama on Air Force One to Atlanta that the United States anticipates that its troop commitment “will galvanise the international community” to act.

“People around the world, knowing that the United States Department of Defence is involved in this effort, can have some more confidence that the effort is well run, that it will be well executed and that they can contribute to the effort knowing that they’ll have the necessary resources to succeed,” Earnest said.

“People around the world, knowing that the United States Department of Defence is involved in this effort, can have some more confidence that the effort is well run, that it will be well executed and that they can contribute to the effort knowing that they’ll have the necessary resources to succeed,” Earnest said.

Ebola spreads rapidly, causes fever and uncontrolled bleeding. The latest outbreak has killed more than half of its victims. Its impact has been greatest in Liberia and neighbouring Guinea and Sierra Leone.

The virus has so far killed 2,461 people, half of the 4,985 people infected, and the death toll has doubled in the past month, WHO’s Aylward said.

Aylward said it could be weeks or months before treatment centres can be built with enough beds to isolate those with the disease and stop its spread.

U.N. officials issued stern warnings of the scale of the task ahead, saying the cost of the response had multiplied tenfold in a month to $1 billion. A previous forecast of 20,000 Ebola cases no longer seemed high, one said, as weak West African healthcare systems have been overwhelmed.

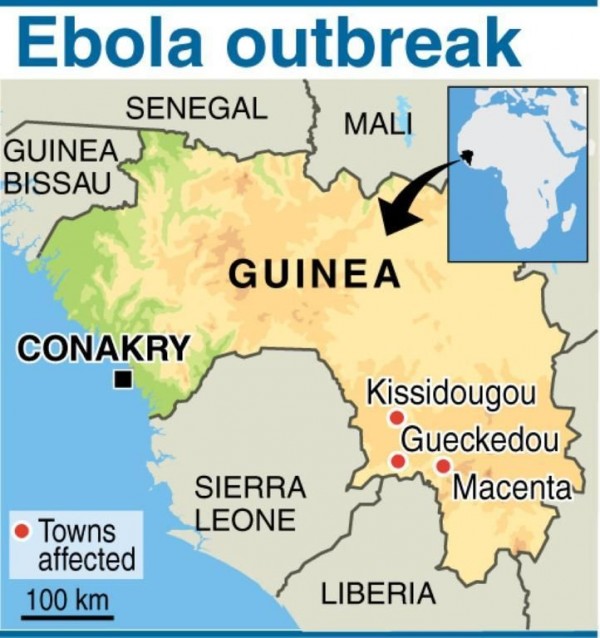

The outbreak was first confirmed in the remote forests of southeastern Guinea in March, then spread across Sierra Leone and Liberia. A handful of deaths have also been recorded in Nigeria, Africa’s most populous country.

The disease has crippled weak health systems, infecting hundreds of local staff in a region chronically short of doctors. The WHO has said that 500 to 600 more foreign experts and at least 10,000 more local health workers are needed.

“It is not enough to provide protective clothing when you don’t have the people who will wear them,” Ghana’s President John Dramani Mahama said during a visit to Sierra Leone.

The U.S. deployment revives memories of Liberia’s war years, when Monrovia residents piled bodies of the dead at the U.S. embassy to persuade Washington to send troops. In 2003, a U.S. mission helped African forces stabilise Liberia after 14 years of war, in which some 250,000 people are thought to have died.

Liberia’s President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, who wrote to Obama last week to plead for direct U.S. intervention, was due to address her country on Wednesday. Guinea and Sierra Leone have not yet commented on the planned U.S. deployment.

‘OUR FRIENDS’

“We know our friends in times of crisis. The U.S. has always been there for us,” a senior Liberian government official told Reuters, asking not to be further identified.

The U.S. intervention comes as the pace of cash and emergency supplies dispatched to the region accelerates.

Washington has sent about 100 health officials and committed some $175 million in aid so far. Other nations, including Cuba, China, France and Britain; have pledged medical workers, health centres and other forms of support.

Critics, including regional leaders, former U.N. Secretary-General Kofi Annan and Peter Piot, one of the scientists who discovered Ebola, have said international efforts have so far fallen woefully short.

“It is now up to other governments to equally scale up their support in Sierra Leone and Guinea,” Piot, now director of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, told Reuters.

“These efforts should make a difference for those infected, and help to reduce transmission. However the big challenge is to stop transmission in the community, which requires profound knowledge of local beliefs and behaviours,” he added.

Many neighbouring African countries have shut borders and cancelled flights to affected countries, making the humanitarian response more difficult.

A draft U.N. Security Council resolution on Ebola, obtained by Reuters, calls on U.N. member states, particularly in the region, to lift general travel and border restrictions.” The resolution could win approval later this week.

In a speech to the United Nations, the president of medical charity Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF), which has some 2,000 staff members fighting the disease in the region, said other countries need to follow the U.S. lead.

“We need you on the ground. The window of opportunity to contain this outbreak is closing,” Dr. Joanne Liu, said. “We need more countries to stand up, we need greater deployment, and we need it now. This robust response must be coordinated, organised and executed under clear chain of command.”

Reuters