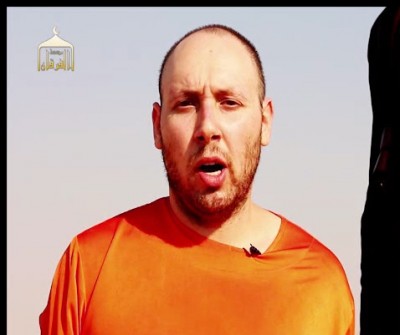

Pinecrest, Florida – Journalist Steve Sotloff lost his life to Muslim militants who kidnapped him and proudly posted his decapitation on the Internet. But he kept a secret from them to the very end: He was Jewish, and an Israeli citizen.

Sotloff, who had managed to conceal his Jewish identity for years as he reported from potentially hostile spots around the Middle East, kept up his remarkable deception even during the year he was held after being kidnapped by the murderous Islamic State militia.

He prayed in the direction of Jerusalem and faked stomach aches so he could fast on Jewish holy days. Sotloff’s friends, who began talking about his trickery for the first time after the Islamic State posted a video of his mutilated body Tuesday, say they are certain the jihadist group never caught on.

“Of course, none of us have talked to [the Islamic State] about it,” said Danielle Berrin, a childhood pal who was in close touch with Sotloff until his abduction in August 2013. “But don’t you think they would have been bragging about it if they knew they were killing a Jew?”

Tuesday’s revelations came as reaction to Sotloff’s death — Islamic State’s second public murder of an American hostage in two weeks — continued to reverberate around the world, nowhere louder than the White House.

“Those who make the mistake of harming Americans will learn that we will not forget, and that our reach is long and that justice will be served,” said President Barack Obama at a news conference during a state visit to Estonia. Vice President Joe Biden, during an appearance in Maine, warned that the U.S. government will pursue the killers to “the gates of hell.”

At the Sotloff family home, the reaction was more somber. The family announced a memorial service, open to the public, at 1 p.m. Friday at Temple Beth Am, 5950 SW 88th St.

Sotloff’s abduction has been shrouded in secrecy from the beginning. His family and the media outlets he worked for, including Time and Foreign Affairs magazines, didn’t reveal his kidnapping for fear of complicating efforts to win his release.

They also tried to scrub the public record of anything that suggested Sotloff was Jewish or Israeli. The Israeli government suppressed all archives that showed his citizenship. Even a brief biography of his mother, Shirley, which mentioned her parents were Holocaust survivors, was erased from the website of the Temple Beth Am Day School, where she taught.

(Though, as one of Sotloff’s friends wistfully noted, “on the Internet, nothing is ever really deleted.” The New York Times stumbled onto a cached copy of the biography and published a story on its website identifying Sotloff as the grandchild of Holocaust survivors before quickly expunging the reference. “We did not want to publish anything that could jeopardize — or be perceived as jeopardizing — his safety,” Times foreign editor Joe Kahn told the Miami Herald on Wednesday.)

(Though, as one of Sotloff’s friends wistfully noted, “on the Internet, nothing is ever really deleted.” The New York Times stumbled onto a cached copy of the biography and published a story on its website identifying Sotloff as the grandchild of Holocaust survivors before quickly expunging the reference. “We did not want to publish anything that could jeopardize — or be perceived as jeopardizing — his safety,” Times foreign editor Joe Kahn told the Miami Herald on Wednesday.)

Even when the Islamic State announced Sotloff’s captivity to the world last month in an Internet video — along with a blunt threat to kill him if U.S. foreign policy didn’t change — relatively few details emerged. Many news organizations, including the Miami Herald, learned that Sotloff was Jewish but held the fact back from their stories.

On Wednesday, details began to emerge for the first time. Among the first was a tweet from an Israeli foreign ministry official that announced: “Cleared for publication: Steven Sotloff was Israel citizen RIP.”

Sotloff grew up in Miami and attended the same school where his mother taught pre-school, but for the past decade his heart was in Israel after he had what friends called “a Jewish roots experience.”

Like hundreds of thousands of young Jews, he took an all-expenses-paid educational trip to Israel sponsored by the Taglit-Birthright Israel foundation. Sometime afterward, he returned home to tell his parents he was dropping out of the University of Central Florida after three years pursuing a journalism degree and moving to a Tel Aviv suburb to major in government studies at the Interdisciplinary Center Herzliya, a private college.

“They weren’t too thrilled about the idea of this,” said the Sotloff family’s rabbi, Terry Bookman. “But they didn’t get in his way.”

After graduating in 2008, Sotloff jumped into freelance journalism. He occasionally reported from Europe, including a story on Vienna’s ancient but beleaguered Jewish colony. But more often he was in the front lines of the Middle East, writing about the victims of the region’s endless wars.

Sotloff wanted “to give a voice to people that didn’t have a voice,” said his Interdisciplinary Center classmate Daniel Isaacsohn, 34, now a corporate personnel specialist in Boston . Agreed his elementary school playmate Berrin: “As a journalist, he was drawn to places of tumult and conflict.”

But those places, including Libya and Syria, are not friendly to Jews or Israelis, so Sotloff became adept at fudging his background. “He had all these hilariously great cover stories for his name,” Berrin said. “He would tell people he was Chechen. And that he was a Muslim without any formal religious training.”

The oddball cover stories reminded Berrin very much of the mischievous little boy she went to school with. “I remember him as this goofy, really playful, fun-loving kid,” she said. “He went off to prep school in New Hampshire, and we were out of touch for a long time. And then, out of the blue, I got this email from him. And I was really startled that he had grown into this serious, indefatigable and fearless journalist.”

Some of Sotloff’s friends, however, thought a little bit of fear might be good for him. On Sotloff’s visits home to Pinecrest, Rabbi Bookman cautioned him that Syria, torn by a tri-cornered civil war in which journalists are mostly considered targets rather than neutral observers, was too dangerous.

“There was no real stopping him,” Bookman said. “There was no talking him out of it. He knew how to be careful. He had been there before.”

And, Bookman added, he understood Sotloff’s passion. “He had a big humanist streak,” the rabbi recalled. “He was always curious about the Arab world; he became an Islamophile. He believed in the Arab spring. [And] his writing was exquisite.”

Bookman’s warning about Syria, however, was deadly right. Sotloff was abducted shortly after he and his driver crossed the border from Turkey. And, except for a single phone call to his parents last December, he was never heard from again.

But another foreign hostage who for a time was imprisoned with Sotloff but later released told his family that their son successfully deceived his captors about his Jewishness and even privately taunted them by watching them saying Muslim prayers in the direction of Mecca, then adjusting the angle so he could pray toward Jerusalem.

Mrs. Sotloff, certain it no longer mattered, videotaped a plea to the Islamic Nation last week in which she might have given away her son’s Jewish identity. “I ask you to use your authority to spare his life,” she said in the video, “and to follow the example set by the Prophet Mohammed, who protected people of the book.”

“People of the book” is a reference to a phrase in the Quran and sometimes an Islamic codeword for Jews. But it can also refer to Christians and some believers in some other pre-Islamic religions.

In any event, Sotloff’s religion probably had nothing to do with his fate. “They’re killing Christians,” Bookman said. “They’re killing Zoroastrians. They’re killing Shia. Putting a Jew into the hopper, I don’t know if it matters.”

STEVEN SOTLOFF SERVICE

There will be a memorial service for Steven Sotloff on Friday at 1 p.m. at Temple Beth Am, 5950 SW 88th St. The service will be open to the public.

Originally published in Miami Herald

BY CAROL ROSENBERG AND GLENN GARVIN

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.