By:DAVID E. SANGER

Behind President Obama’s decision on Friday to extend the Iran nuclear negotiations for four more months is a calculation that the administration has the mix of pressure and incentives just about right: That by keeping the most damaging sanctions, but giving Tehran a taste of what access to its overseas cash reserves might mean, a deal is possible.

Congress, and some nuclear experts pushing for a harder line, strongly disagree. It was overwhelming sanctions, and the pressure of covert action against Iran’s nuclear program, that brought the country to the table, they argue. To get a final deal, they contend, the formula is simple: More sanctions, more pressure, and behind it all the lurking threat of military action.

“We can’t let Iran buy more time to make a nuclear bomb,” said Senator Mark S. Kirk, the Illinois Republican and the author, with Senator Robert Menendez of New Jersey, a Democrat, of one of the major efforts for additional sanctions. His statement came late Friday night, shortly after Iran, the United States and five other nations involved in the talksannounced an extension until November 24.

“While the United States has repeatedly offered extremely generous incentives for Iran to dismantle its illicit nuclear infrastructure, Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei keeps rejecting the offers,” he said. “It’s time for expanded nonmilitary pressure to back up our diplomatic outreach to Iran.”

Mr. Obama will win this argument in the short term. The four-month extension is not long enough for Congress to take decisive action, and Mr. Obama has signaled that he would veto more sanctions. But over the longer term, administration officials know they have a deeper problem. No agreement with Iran is going to have the kind of guarantees Congress has demanded to prevent Tehran from producing a weapon. History suggests no such guarantees are possible; there are simply too many other pathways for a determined country to get a weapon.

Yet if a deal were struck, ultimately Mr. Obama would most likely have to persuade Congress to reverse the sanctions against doing business with Iran that have been piling up for more than a decade. That helps explain the Nov. 24 date: Mr. Obama would still have a little over a month to push sanctions relief through the Senate while it was still controlled by the Democrats, in case his party loses that control in the midterm elections.

Iran gets slightly more relief under the negotiation extension: It will have access to $2.8 billion in assets that are held outside the United States, a small fraction of what is frozen. But in the House, more than 300 members have already signed a letter opposing a lifting of American sanctions unless an agreement curtails Iran’s missile development and stops its support for Hamas and other terror groups — issues that are not even on the table in the nuclear negotiations in Vienna.

“There’s an astonishing, visceral opposition to any kind of deal, and it’s not just among the Republicans,” said a key administration strategist who insisted on anonymity because of the sensitivity of the negotiations.”And I’m not sure there’s a plan yet to deal with it.”

It may not be an issue. There is no guarantee that a deal will be reached in the four extra months of negotiations.

The past week seemed like the moment. The top three American diplomats were all in Vienna simultaneously: Secretary of State John Kerry, the deputy secretary, William J. Burns, and the undersecretary of state for political affairs, Wendy Sherman, who has also been the lead negotiator. Foreign ministers from Europe flew in, briefly. So did the brother of President Hassan Rouhani of Iran, who attended sessions with Mr. Kerry, then flew back to Tehran, presumably to report directly to his brother, who was elected on a platform of getting the oil, gas and other sanctions lifted.

There is no question significant progress was made, as one administration official put it in a background telephone call with reporters late Friday night, on issues that “get at fundamental pathways to a nuclear weapon.”

Among them is an understanding about how Iran’s soon-to-be-finished heavy water reactor near the town of Arak would be modified to reduce its output of plutonium, one of the two fuels that Iran could use for a weapon. There is discussion about turning the giant underground facility called Fordow — built under a mountain outside the holy city of Qum — into some kind of research and development facility. To the Americans, and the Israelis, that would be an improvement over its current status as Iran’s secondary location for enriching uranium, in a place so deep that the Israelis fear they could not bomb it; even some American officials wonder if their biggest bunker-busting bomb, built for the job, could penetrate the facility.

But that leaves unresolved the central conundrum that has hung over the talks: Can Iran’s supreme leader be persuaded to give up the country’s hopes of building an industrial-scale enrichment capacity, ostensibly to produce fuel for its one working reactor and a series of future reactors for which Iran has not even broken ground? Ayatollah Khamenei and the Iranian military have opposed any agreement that dismantles existing facilities and does not allow Iran, in the near future, to produce as much as it wants.

American officials say the rationale that Iran needs to produce its own fuel is fanciful; there is plenty on the market and ways to assure Iran of continued supply.

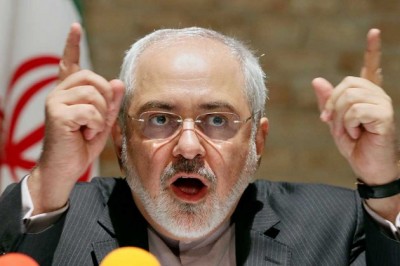

On this point, Iran’s foreign minister, Mohammad Javad Zarif, says Iran cannot budge for reasons of national security and national pride. Iran, he said, has been blocked from getting fuel for its reactors for 20 years. Russia may be its supplier now, he said, but cannot be trusted to remain so. Even raw materials are hard to come by.

Mr. Zarif, in an interview, argued that the sanctions Congress is so proud of have been counterproductive. Before they began in earnest, he said, Iran had 200 centrifuges installed in its facilities; now it has 22,000. More pressure, he contended, will only drive Iran’s leadership to more defiance. Some in the Obama administration agree, saying there is a “sweet spot” in sanctions where the continuing, gnawing pressure of oil, gas and financial sanctions, which they vowed Friday night to continue, would take their toll, and the prospect of relief would create political pressure in Tehran for a deal.

But Gary Samore, President Obama’s former top adviser on eliminating weapons of mass destruction, took a harder line on Friday night. Now the president of United Against Nuclear Iran, an advocacy group, Mr. Samore and the organization’s chief executive, Mark D. Wallace, argued that to get the leverage the administration needs it must “make clear that Iran remains closed for business and that the uncertainty surrounding these nuclear negotiations makes the business climate in Iran far too risky” for Western capital to re-enter.

And, they contended, the negotiating partners should go farther and “agree on decisive sanctions that would constitute a virtual economic blockade of Iran should Iran fail to agree to an acceptable deal” in the next four months.

NY Times

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.