By: David Ignatius

By: David Ignatius

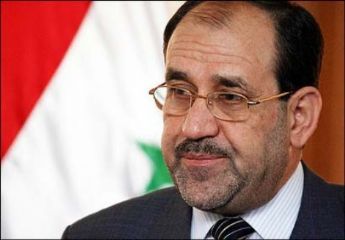

The stunning gains this week by Iraq’s Sunni insurgents carry a crucial political message: Nouri al-Maliki, the Shiite prime minister of Iraq, is a polarizing sectarian politician who has lost the confidence of his army and nation. He cannot put a splintered Iraq together again, no matter how many weapons the Obama administration sends him.

Maliki’s failure has been increasingly obvious since the elections of 2010, when the Iraqi people in their wisdom elected a broader, less-sectarian coalition. But the Obama administration, bizarrely working in tandem with Iran, brokered a deal that allowed Maliki to continue and has worked with him as an ally against al-Qaeda. Maliki’s coalition triumphed in April’s elections, but the balloting was boycotted by Sunnis.

Given Maliki’s sectarian and authoritarian style, a growing number of Iraq experts are questioning why the Obama administration continues to provide him billions in military aid — and is said to be weighing his plea for lethal Predator drones. The skeptics include some who were once among Maliki’s champions.

“I believe that Maliki has never had the energy or intent” to unify Iraq, says Derek Harvey, a professor at the University of South Florida who advises Centcom and is one of the leading U.S. experts on Iraq. “He was a bad choice in the beginning and our embrace of him was an error.”

A retired U.S. four-star commander asks in an interview: “How in the world can you keep betting on this number [Maliki] given what’s happened?” He believes Maliki is incapable of retaking the territory he has lost, and he wonders when Iran’s Quds Force will intervene to rescue Maliki’s collapsing army.

Maliki’s U.S.-trained army has suffered a series of crushing defeats, as Sunni insurgents from an offshoot of al-Qaeda captured the northern Sunni cities of Mosul and Tikrit and swept toward Baghdad. Already the Sunni extremists control most of western Iraq.

The Shiite-led Iraqi military has crumpled in battle, fleeing the battlefield and leaving behind tanks, Humvees and other vehicles. In cities such as Fallujah, cleared by American troops at great cost, al-Qaeda and its progeny are now dominant.

Maliki’s sectarian political style has helped create this disaster. He has gutted the army of the commanders he suspected of plotting against him. One U.S. expert likens him to Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, who purged the Red Army on the eve of World War II.

“He has replaced his generals with Shiite commanders who represent not competency, but political loyalty” to Maliki and his Dawa Party, says Harvey.

The victors belong to an extremist Sunni faction known as the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria. These pitiless, battle-hardened fighters, remnants of what was known as al-Qaeda in Iraq, have attracted jihadists from around the world. One of their most effective commanders in Mosul is said to have been a Georgian-born Chechen known as Omar al-Shishani. The Chechen was also a key ISIS commander in recent battles around the Syrian city of Aleppo — an illustration of the group’s potent cross-border reach.

ISIS forces have swept south along Highway 1 from Mosul, swelling their ranks by liberating 2,000 to 3,000 jihadist fighters from a prison in Nineveh province. The jihadists have captured so much U.S.-made equipment that it’s reportedly hard to distinguish friend from foe along the chaotic highway south.

Maliki’s forces are said to be drawing their battle lines just above a huge arms depot at Taji, about 20 miles north of Baghdad, which was a key U.S. logistics base during the American occupation, from 2003 to 2010. By consolidating his forces so far south, Maliki is, in effect, conceding the northern cities. Harvey argues that only the pesh merga fighters of Iraqi Kurdistan are strong enough to retake Mosul, but some experts doubt they would launch such a battle unless it was a prelude to a fully independent Kurdistan.

Senior Obama administration officials said Thursday they recognize that Maliki is seen by Iraqi Sunnis as a sectarian figure, and they are pressing him to expand his base in “unity government.” But they said there is no “conditionality” in the U.S. offer of military assistance and that the overriding goal short term is to help Malilki stop the Sunni extremists and prevent the fall of Baghdad.

As the fabric of the Middle East rips apart along sectarian lines, the United States and its allies face a fundamental strategic choice: Can they convene a regional peace conference — which would seek to reconcile Sunni and Shiite forces and their key backers, Saudi Arabia and Iran — in some new security architecture?

Restitching the fabric of Iraq and Syria may be Mission Impossible. But with its focus on counterterrorism and weapons supplies, the Obama administration seems to have decided to treat the region simply as a shooting gallery.

Washington Post

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.