By Matt Lewis

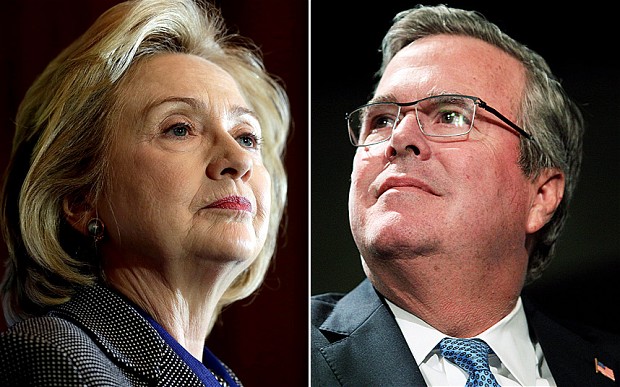

Could the 2016 presidential election turn into a contest between a Bush and a Clinton? Political debate in America last week revolved around whether or not Jeb Bush, Florida’s former governor who is son or brother to two former US presidents – both named George – would jump into the 2016 battle for the Republican presidential nomination.

For a nation that fought a war for independence from the hereditary power of the British Crown, in the person of another fellow named George, the concept of nominating a third Bush to run for the White House against a second Clinton (the former First Lady, Hillary Clinton, who is the assumed Democratic nominee) might sound absurd.

And not just to an outsider. “If we can’t find more than two or three families to run for high office,” Jeb Bush’s mother Barbara said in January. “That’s silly.”

Silliness aside, Mrs Bush’s words haven’t stopped the speculation from swirling. Just last week, the New York Times reported that Andy Card, who was chief of staff to former President George W Bush, said “Republicans should draft Jeb”, adding: “If Jeb Bush doesn’t run for president, shame on us.”

The rush to crown another Bush as the Republican nominee speaks to a few things. First, it is an apparent sign of desperation, which is to be expected when any political party considers the looming possibility of losing a third consecutive presidential election – a real prospect for Republicans just now.

But second, does it speak to a latent dynastic tendency in America? I don’t mean that the US wants a king, as such, but that the concept of elected ruling elites isn’t nearly as much an affront to Americans as they would have you believe.

Americans may pose as a nation of populists and rugged individualists, but what else explains our penchant for promoting certain families, from the Adamses who provided our second and sixth presidents through to the Kennedys, the Clintons and the Bushes?

We’re so keen on dynasties that we even have a backup plan for 2016. In the event than Jeb Bush doesn’t seek or win the nomination, Rand Paul, the Republican senator, will be in pursuit of it as well – himself the son of the congressman and former presidential candidate, Ron Paul. (Unlike the Bushes, the Pauls are thought of as political outsiders, despite the fact that the younger Paul is now a denizen of the US senate, the most exclusive club in America – making him an insiders’ outsider, I suppose.)

Further underscoring that this is an American tendency rather than mere coincidence is the fact that we now also have a growing number of presumed heirs to the throne. George P Bush, Jeb’s son, has taken his first steps into politics. Liz Cheney, daughter of the former vice president Dick Cheney, had a tilt at becoming the Republicans’ senate candidate in Wyoming.

It may now be just a matter of time before one of them – or perhaps Tagg Romney, scion of failed White House candidate Mitt – runs up against Chelsea Clinton for president?

Some maintain that this is less an example of dynastic tendencies, let alone nepotism, than a case of families sharing an interest and passing traditions down from one generation to the next – like a sort of family business.

This makes running the most powerful country in the world sound as quaint as being a grocer’s son. Of course, we acknowledge the importance of both nature and nurture: we talk a lot about genius. But running a family grocery is altogether different from running a nation.

Ultimately, our penchant for dynasties exposes a contradiction within the American psyche. While Americans don’t much care for hereditary rule, we do care a great deal about making money – and it is in the context of capitalism and commercialism that it makes business sense for the Republicans to nominate Jeb Bush.

Ever wonder why Hollywood churns out so many second-rate but profitable, sequels and remakes? It’s because, no matter how bad the film may prove to be, studios are almost guaranteed to make money from a familiar title with a proven track record.

It helps if you don’t think of the Bushes and the Clintons as political nobility but as established names: it’s all about the brand.

The Telegraph

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.