So Kiev’s revolt has become revolution: in a single tumultuous day the embattled President Viktor Yanukovych fled the capital as Parliament voted to impeach him and named their Speaker as interim president.

So Kiev’s revolt has become revolution: in a single tumultuous day the embattled President Viktor Yanukovych fled the capital as Parliament voted to impeach him and named their Speaker as interim president.

Crowds flocked into his palatial mansion outside Kiev, abandoned by its guards, and gazed in wonder and disgust at Yanukovych’s pet peacocks and private boat-shaped restaurant.

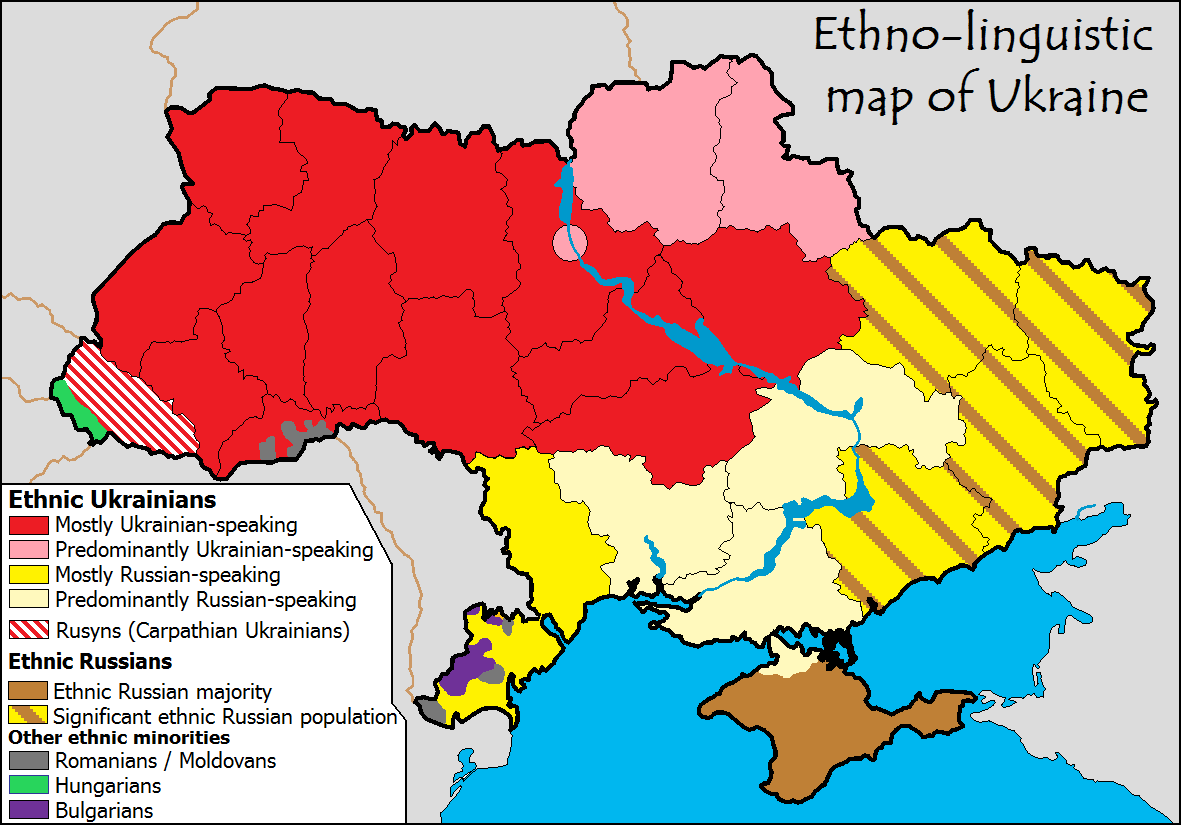

Meanwhile his arch-rival Yulia Tymoshenko was released from jail on Saturday – while the pro-Russian East and South of Ukraine appealed to Moscow to intervene against what Yanukovych dubbed a “coup” by “thugs and terrorists.”

Will Ukraine break up as a country? Will its new leadership be pro-EU or pro-Russian? Should we even care?

The answers to the first two questions are still in play. But yes, we should care very much about the fate of Ukraine for three important reasons: the future of Russia, of Vladimir Putin, and of the European Union itself will be shaped by events in Kiev over the next three months.

On the face of it, its true that Ukraine doesn’t look very important. It’s an economic basket case with a GDP per capita of under $4000 a year and zero growth for the last two years. The most famous living Ukrainians are probably American actresses Mila Kunis and Milla Jovoich, both of whom left as little kids.

Little of world-historical significance has happened there apart from the conversion of Rus to Christianity in 988 and the Battle of Poltava in 1709 when Russia replaced Sweden as the superpower of the Baltic. Sorry, Ukraine, but frankly for most of its history the place has been the battleground where Europe’s great powers – primarily Russia, the Ottoman Empire, the Hapsburg Empire, the German Reich – met to duke it out between themselves.

And yet it’s precisely because Ukraine remains a battleground today that its so crucial. “Without Ukraine,” former US Secretary of State Zbigniew Brzezinski famously said, “Russia is no longer an empire.”

Many liberal minded Russians believe that would be a good thing, most of all for Russia itself — it might allow future leaders to squander less resources on showing off and trying to dominate the world and devote more attention to delivering basic rights to ordinary Russians. But as the $50 billion Winter Olympics in Sochi showed, the Kremlin is very serious about establishing Russia as a great world power, and has no intention of letting Kiev go without a fight.

In the wake of Yanukovych’s flight from Kiev Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov labeled the opposition “rampaging hooligans” and called on Europe to rein them in. At the same time, ominously, his ministry’s Twitter feed began sharing news tit-bits that looked ominous like the prelude to a military intervention.

“Belarusian tourist bus came under fire in Rovno region #Ukraine Russian citizen was heavily wounded. We demand to ensure safety of civilians,” Russia’s Foreign Ministry tweeted Saturday. “Delegates in Crimea asking for protection from Russian army.”

In 2008 Russia wasn’t shy about fighting a war on behalf of two tiny protectorates inside Georgia that weren’t even ethnically Russian. In Crimea, on the other hand, over 60 percent of the population is Russian speaking – and Moscow leases a large naval base at the port of Sevastopol, headquarters of the Russian Black Sea Fleet.

A Russian military intervention in Ukraine would be far more dangerous than Moscow’s short, sharp war in Georgia, and could pit Russia against the West in a shooting war for the first time since the 1850s, when Britain and France invaded, yes, the Crimea. Only a leader obsessed with re-building Russia’s empire would ever risk it.

Which brings us to Putin. He’s staked a huge amount of personal prestige on backing Yanukovych over the last 10 years — and he’s been humiliated not once but twice. The first time was in 2004 when protesters on Kiev’s Maidan overturned an election rigged by Yanukovych with Moscow’s help.

Now it’s happened again, with Putin’s man once again ousted by another show of people power. The problem is that Putin can’t let the pro-western protesters win — it would be deeply damaging to his own prestige, as well as raising the specter of people power in Russia itself, something which has terrified the Kremlin since the coloured revolutions which swept the former Soviet Union in 2003-4.

Three, the outcome of Ukraine’s meltdown is crucial to the future credibility of the European Union. So far, in the words of Ukraine watcher Andrew Wilson, Brussels has “taken a baguette to a knife fight.”

With zero growth, deflation, soaring unemployment and populist anti-European and anti-immigrant parties rising across the continent, the EU has plenty of problems of its own. The prospect of accepting gigantic, populous, and poverty-stricken Ukraine into the already troubled Union is not high on the agenda. That’s why Brussels allowed Putin’s ruthless ambition and cold cash to trump their weak offers of vague cooperation.

With zero growth, deflation, soaring unemployment and populist anti-European and anti-immigrant parties rising across the continent, the EU has plenty of problems of its own. The prospect of accepting gigantic, populous, and poverty-stricken Ukraine into the already troubled Union is not high on the agenda. That’s why Brussels allowed Putin’s ruthless ambition and cold cash to trump their weak offers of vague cooperation.

But now the foreign ministers of Germany, Poland and France have showed some backbone and real political clout. The three ministers forced a ceasefire on Friday after 20 hours of negotiations. Now Radoslaw Sikorski, the Polish foreign minister, is playing a key role in setting up a framework for elections on May 25 and ensuring that European observers have a role in the process. Crucially he’s also insisting that there has been “no coup in Kiev and that the actions of parliament are legal.”

But the real test will not be whether European ministers will be able to shepherd through a new political order in Ukraine, but rather whether they can follow through with some real promises of economic aid that can trump Russia’s. More important still, the question is whether Europe can stand up for the ideals of personal freedom and democracy that it claims to support.

At stake is the concept of Europe as a “civilization project,” as former French President Valery Giscard D’Estaing called it. Is the Union able to project and protect democracy in its close neighborhood and act as a beacon of stability, freedom and prosperity – or is it just a collection of squabbling and mismatched nations locked in an unhappy marriage?

That’s why the endgame of the Yanukovych regime is about much more than the future of Ukraine. It’s about the future of Russia, the credibility of Europe and the Putin’s personal face.

“It’s very important for us to continue to try to persuade Russia that this need not be a zero sum game,” British Foreign Secretary William Hague said Sunday. “It’s in the interest of the people of the Ukraine to be able to trade more freely with the EU, it’s in the interests of the people of Russia for that to happen as well.”

Unfortunately for Ukraine, with so much prestige at stake it’s unlikely that Moscow will sit back and simply let Ukraine’s people decide their own future.

By Owen Matthews

Newsweek

Top photo: File photo of ousted President Viktor Yanukovych with Russian president Vladimir Putin in Moscow

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.