The night before a round of high-stakes nuclear talks with Iran, U.S. President Barack Obama told his chief of staff he had “absolute confidence we have the right team on the field.”

The night before a round of high-stakes nuclear talks with Iran, U.S. President Barack Obama told his chief of staff he had “absolute confidence we have the right team on the field.”

Obama was not referring to his public negotiating team, led by senior State Department official Wendy Sherman, nor even to his secretary of state, John Kerry, who was soon to sweep in from Tel Aviv to join the early November discussions in Geneva.

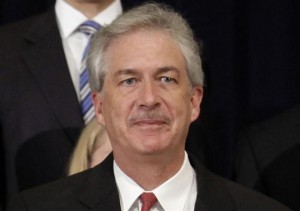

Rather, White House chief of staff Denis McDonough recalled, Obama was talking about a secret group led by Bill Burns, Kerry’s discreet, disciplined and self-effacing deputy.

At times using U.S. military aircraft, hotel side entrances and service elevators to keep his role under wraps, Burns undertook arguably the most sensitive diplomatic mission of Obama’s presidency: secret talks with Iran to persuade it to curb its nuclear program.

In picking Burns, seen by his peers as a leading U.S. diplomat of his generation, Obama gave the envoy, who speaks Arabic, French and Russian, a chance to ease more than 30 years of estrangement between the United States and Iran.

If it ensures Tehran does not build a nuclear bomb, the Iran deal could stand as the capstone to Burns’ 31-year diplomatic career.

If it fails, it could bring Israel or the United States closer to a military strike on Iran and fuel criticism that Washington squandered its best opportunity for a peaceful solution by appeasing Iran rather than pressuring it further.

Current and former U.S. officials, including four former secretaries of state, describe Burns as well suited to dealing with the Iranians, with the sensitivity to see Tehran’s perspective and the tenacity not to compromise U.S. interests.

“He is steady, reliable, intelligent, disciplined and – in his understated way – persuasive,” said former U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger.

“I like to hear his judgments and can learn from them,” Kissinger told Reuters. “That’s not something I volunteer very often.”

He said he saw Burns’ deft touch in the discreet way the diplomat, then ambassador to Russia, reported private conversations between Kissinger and Russian President Vladimir Putin back to Washington.

“I wanted to make sure they were not in the cable traffic lest they leak,” Kissinger said. “He handled that with great skill.”

Even those who square off across the table speak well of Burns.

He “knows Iran very well and also understands Iran’s culture, expectations and position in the region,” said a senior Iranian official, speaking on condition of anonymity. “Sometimes during the talks Iranian negotiators get angry and pressure him, but he remains calm and patient.”

BUREAUCRATIC SKIRMISHES

Burns, 57, who has a lanky frame that he used to good effect on the basketball court in his youth, has executed the rarest of Washington careers. He has taken on politically perilous assignments such as heading the State Department’s Middle East shop during the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq, all without a hint of personal failure or personal controversy.

Running the Bureau of Near Eastern Affairs, which handles Middle East policy, from 2001-2005 made him a participant in the epic struggles between the State and Defense Departments over the war and its aftermath – battles the Pentagon largely won.

Burns, who declined to be interviewed for this article, is no stranger to bureaucratic infighting, though colleagues sometimes conduct skirmishes on his behalf. “If an elbow has to be thrown, usually it’ll be thrown by someone else for him,” said one U.S. official.

In recent years, officials say, Burns has acted as liaison between the Obama White House, which directs foreign policy with a firm hand, and the State Department, where mid-level officials sometimes complain of being kept in the dark.

Over the past nine months, Burns, along with Jake Sullivan, Vice President Joe Biden’s national security adviser, met secretly with Iranian officials five times in Oman and Switzerland.

Their assignment became public only when Tehran and six major powers reached a November 24 agreement for Iran to constrain its nuclear program for six months in exchange for sanctions relief that Washington estimates at $7 billion.

Critics have targeted the deal rather than Burns. Some argue that the sanctions relief is worth more than the White House says, and will undercut U.S. economic leverage on Iran.

Former President George W. Bush was skeptical of talking directly about the nuclear issue with Iran. But in 2008, his final year in office, Bush sent Burns to meet with the Iranians, joining envoys from Britain, China, France, Germany and Russia.

“There was some skepticism in some quarters of the administration,” former Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice told Reuters. “When I said to the president, ‘Well it’s going to be Bill Burns,’ he said: ‘He’ll be able to handle it.’”

Asked if Burns had any faults, Rice could only think of one: a demeanor so low-key that he sometimes does not generate headlines that could advance an administration’s agenda.

His style is in sharp contrast to that of another top diplomat of the era, the late Richard Holbrooke, known for his outspokenness and self-promotion.

“I sometimes think that if Bill were more demonstrative publicly, it could be helpful,” Rice said. “It takes a little pressure off the secretary. But Bill is just so understated that that doesn’t happen.”

‘A CAPACIOUS MIND’

Burns’ understated style was evident as an honors student at Philadelphia’s LaSalle University, which his father, an Army general and former head of the U.S. Arms Control and Disarmament Agency, also attended.

“Bill would sit on the right side, near the back of the room, with his head looking down at the floor, his hands clasped between his knees, and I don’t think he ever took a note,” said George Stow, who teaches history at LaSalle. “I thought, oh this boy’s in trouble come the first exam.”

“Well, I opened the blue book for the first exam and it was astounding. It was page after page after page and filled with references and quotations from books and sources that I had never mentioned,” he added, saying Burns had “a capacious mind.”

Stow later sponsored Burns for a Marshall Scholarship, to study in Britain. The idea came from the professors, Stow said. “Bill would never, if I may use such a term, be that pushy.”

Despite the absence of obvious self-promotion, Burns has had an almost gilded career, spent more in Washington than abroad.

A string of staff jobs that are coveted, if exhausting, plums, put Burns at the right hand of officials such as Colin Powell, President Ronald Reagan’s national security adviser, and Warren Christopher and Madeleine Albright when they were secretaries of state.

Powell said Burns had a soft-spoken confidence as a young man and offered unvarnished advice behind closed doors.

“I don’t have people around me who pull their punches. I have people around me who will tell me when I have got no clothes on,” Powell told Reuters.

Richard Armitage, Powell’s deputy secretary of state, said Burns was part of a State Department leadership team that did not so much oppose the 2003 Iraq invasion, as favored a less unilateral approach to ousting dictator Saddam Hussein.

“Was he unhappy? Yes. We were all unhappy with the way we were going to war,” Armitage said, adding he, Powell and Burns favored obtaining a second U.N. Security Council resolution to explicitly authorize the use of force in Iraq.

While known for his courtesy, Burns is not shy about advocating for his preferred policies.

Jim Jeffrey, Bush’s deputy national security adviser, said Burns had swum against the tide in a skeptical Republican administration to make the case for engaging Tehran.

“He pushed very hard in 2008 to have contact with the Iranians,” making his case through then Secretary of State Rice and informally lobbying the national security council staff, Jeffrey said.

Those 2008 dealings with the Iranians helped pave the way to the November nuclear deal, Jeffrey said.

“This was one of the first steps that laid the ground work for what we have today, and laid the groundwork for the Iranian sympathy for and trust in Bill Burns.”

Reuters

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.