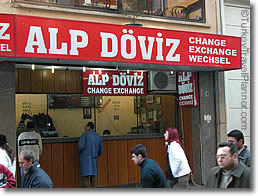

The volume of business for the money changers near Istanbul’s Taksim Square has dropped 70 percent since mass protests broke out against Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan over a week ago.

The volume of business for the money changers near Istanbul’s Taksim Square has dropped 70 percent since mass protests broke out against Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan over a week ago.

“Everyone’s going to get affected. The banks. The stock market. The workers will suffer, and the bosses,” says one of the staff, Sahin Ozcetinkaya, 53. “No country’s economy will ever develop with chaos.”

And it is not just his customers — mostly tourists — that are taking fright from days of tear gas and water cannon here at the heart of Turkey’s powerful economy.

The Istanbul stock market plunged last week and analysts warn that the foreign financing that has fuelled an economic spurt during Erdogan’s decade in office could diminish too.

Turkey is “dependent on foreign capital to finance investment”, wrote Neal Shearing, an analyst at Capital Economics in London.

With thousands angrily accusing Erdogan of authoritarianism in pushing conservative social reforms, “the risk now is that a renewed period of political uncertainty dents confidence and causes investment flows to reverse”.

Victor in three elections in a row, Erdogan has overseen strong economic growth — an average five percent a year since he first won office in 2002.

He also brought stability to Turkey after decades of turbulent party politics and a string of coups from the 1960s, — although critics say this has been partly achieved by jailing hundreds of military officers.

The mostly young, middle-class protesters now yelling in the street for him to resign complain not about the economy but what they call Erdogan’s authoritarian style.

Erdogan has blamed his troubles on various groups of outsiders — unnamed agitators and “terrorists”, plus what he calls an “interest rate lobby” of speculators pushing for high returns.

“Dear brothers, we have come this far by building, producing and strengthening Turkey… We have come this far despite the interest rate lobby,” Erdogan said on Friday.

“They think they can threaten us by speculating in the market. They should know we will not let them feed on the sweat of this nation.”

After Erdogan’s defiant speech on Thursday, the rate of return on Turkey’s benchmark government bond shot up from 6.2 percent to reach 6.9 percent early on Friday — making it more expensive for his government to borrow money.

Analysts saw that as a sign that Erdogan’s rhetoric — harder than that of the ministers under him — was rattling the markets just as much as the unrest on the streets.

That same day, the Istanbul stock market also fell by nearly five percent and the Turkish lira weakened against the dollar. Stocks had plunged 10 percent on Monday at the height of the unrest.

“His more combative tone disappointed the markets,” analyst Deniz Cicek from Turkish lender Finansbank observed.

“Persistence of this stance and the possible resumption of the heavy-handed police response could undermine” investments in Turkey, Cicek warned.

The stocks and lira recovered on Friday after the leader gave a more conciliatory message welcoming “democratic demands”.

Erdogan came to power in 2002 buoyed by protest votes and, by tightening fiscal policies and ushering in foreign money, dragged the country out of an economic crisis.

Growth topped nine percent in 2004 and came close to that again in 2010, according to Turkish national statistics institute.

Foreign media dubbed Turkey an “economic miracle” as the country attracted cash to build bridges, airports and homes.

But it was one of the latest building projects, a plan to redevelop Gezi Park, next to Taksim Square, that sparked the recent unrest.

Protests swelled when police fired tear gas at demonstrators trying to stop the bulldozers on May 31, prompting angry rallies by crowds throwing stones at police. Three people have died in the clashes.

Ratings agency Fitch said the future police response to ongoing protests would govern Turkey’s financial fortunes, stressing that “the economic impact so far is minor” and not enough to damage Turkey’s medium-strength credit score.

In its latest estimate on Thursday, the interior ministry calculated the cost of the unrest at 70 million lira (28 million euros, $37 million) — a tiny speck in an economy of more than $770 billion.

But it warned: “Much will depend on how the authorities respond to the protests. Poorly handled, the situation could escalate, with adverse consequences for the economy.”

In the currency exchange, employee Osman Eren, 33, says he trusts Erdogan to restore order.

Seven employees staff the agency but as tourist hotel reservations have been cancelled, so have the moneychangers’ shifts.

Eren points in exasperation across the road to Gezi Park, where young demonstrators are camping out in a maze of tents and makeshift food stalls.

“I supported them the first day or two. Not any more. If this continues, there’s going to be some serious downsizing,” he said.

“If I’m going to get fired, I support the cops in removing these guys. It’s my future at stake.”

Channel News Asia

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.