Iran’s rial sank about 5 percent in trading against the U.S. dollar on Monday after the central bank said it would change the currency’s official exchange rate, prompting fears of another devaluation as the economy suffers from international sanctions.

Iran’s rial sank about 5 percent in trading against the U.S. dollar on Monday after the central bank said it would change the currency’s official exchange rate, prompting fears of another devaluation as the economy suffers from international sanctions.

The rial was trading in the free market at around 21,510 per dollar, according to Persian-language currency tracking website Mazanex, down from about 20,440 on Sunday.

Most dealers in Tehran’s major currency trading district stopped selling dollars on Monday and removed signs from windows advertising their rates, Mehr News Agency reported. It said the rial fell as low as 22,000 before partly recovering to 21,400.

Central bank governor Mahmoud Bahmani said on Sunday he would announce a change to the government’s “reference rate” of 12,260 rials to the dollar “within the next 10 days”, Iranian media reported.

He did not elaborate, but Iranian media speculated the new reference rate might be between 15,000 and 16,000 rials. Most Iranians are unable to obtain dollars at the official rate and must instead use the free market, which is far more expensive.

Iran’s economy has been hit hard in the past year by sanctions imposed over its disputed nuclear programme. The country has largely been cut off from the international banking system and the rial has lost about half its value against the dollar in the free market.

The sanctions have slashed Iran’s oil exports, which in normal times accounted for nearly four-fifths of its total exports and two-thirds of government revenues. In June, Tehran admitted its oil exports had shrunk between 20 and 30 percent.

In January this year, Iran announced an 8 percent devaluation of the rial to 12,260 against the dollar and said it would enforce a single exchange rate, aiming to stamp out black market traders. But that proved impossible with the sanctions cutting inflows of hard currency into the country.

In March, authorities said they would allow free market trading to coexist with the official rate, and last month they introduced a three-tiered system; the official rate would be used to import basic goods such as meat and medicine, a rate of 15,000 to buy factory machinery and intermediate goods, and the free market rate to import luxuries and other goods.

Mehr quoted Hamid Safdel, deputy minister in the Ministry of Industry, Mining and Trade, as saying the new official rate would be somewhere between 12,260 and the free market rate.

RESERVES

Iran’s decision to depreciate the exchange rate may indicate its foreign exchange reserves are being drained by the sanctions and that in order to conserve them, it realises it must make hard currency more expensive.

Bahmani was quoted by Mehr as saying on Sunday that the government had no problem securing foreign currencies.

At the end of last year Iran had $106 billion of official foreign reserves, enough to cover an ample 13 months of imports of goods and services in normal times, according to the International Monetary Fund.

That suggests Tehran probably faces no balance of payments crisis in the near term. But with oil exports shrinking, a global economic slowdown threatening to push oil prices down further, and banking sanctions making it more expensive for Iran to import many goods, Tehran may feel a growing need to protect its reserves.

In April the IMF predicted Iran’s crude oil exports would shrink to 2.0 million barrels per day this year from 2.5 million last year, causing its current account surplus to drop from 10.7 percent of gross domestic product to 6.6 percent. A deeper cut in oil exports, combined with lower oil prices, could conceivably push Iran into running an external deficit.

Currency depreciation is a risky strategy to deal with this threat, however, because it could fuel inflation. Consumer prices have been rising at annual rates above 20 percent, becoming a political liability for the government.

Ayhan, a university professor in Tehran who declined to give his full name because of the sensitivity of the issue, said any depreciation of the official exchange rate might fuel Iranians’ expectations for even more rial weakness.

“If the government rate becomes 17,000 rials to the dollar, the free exchange rate will become 26,000,” he said.

Reuters

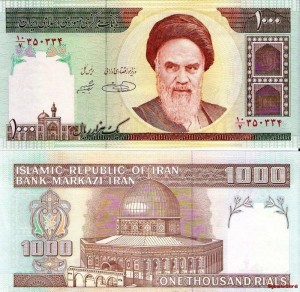

Photo: 1000 Rial banknote . In 1979 , prior to the takeover of Iran by the Islamist regime of Ayatollah Khomeini, this banknote was worth just over $14 but today it is worth less than 5 cents or about 300 times less.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.