By David Gardner

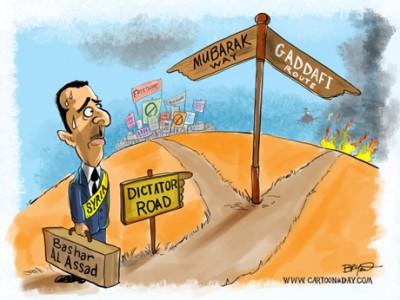

When a dictatorship cannot regain control over a country in revolt for 18 months despite repeated offensives, when it cannot police the countryside away from the main roads, cannot secure the capital or its main trading hub, cannot even protect its innermost citadels and has to pull troops from its borders to protect its palaces, it is finished. This is the case with the dictatorship of Bashar al-Assad, who is still trying to kill his way out of the crisis, even as poorly armed rebels swarm through Syria’s cities and his supporters melt away. He is finished.

Last week’s insurgent bombing of his security cabinet in Damascus was devastating. He lost at least four of his top enforcers, including his brother-in-law, Assef Shawkat, the brains behind the Assad clan and reportedly also his cousin, intelligence chief Hafez Makhlouf, brother of Rami Makhlouf, the financier of the enterprise.

Of itself, the bombing is not a game-changer; the Assads still command far superior firepower. But its emblematic power is irresistible. On top of the stream of defections and desertions from the Syrian army, the regime now has to contend with informers who have infiltrated its inner sanctum. Until the July 18 attack, the Assads had managed to instil terror of retribution inside the castle walls. Now it is they and their entourage who are running scared.

This was not just a deadly blow to the security establishment. It struck the Assad clan network, the mix of security state and gangster enterprise that makes up this regime. Family, clan, predatory business interests and the security praetorians are all enmeshed.

Maher al-Assad, the president’s volatile younger brother, commands the army’s only two reliable strike forces, the Fourth Armoured Division and the Republican Guard – made up, like the security services, mainly of the Alawite minority to which the Assads belong, a heterodox branch of Shia Islam in a country that is three-quarters Sunni. But even the shabbiha, mostly Alawite militia built around smuggling gangs that have been carrying out sectarian cleansing in the Alawite heartlands in the north-west, are often led by the president’s cousins and relatives, such as Nameer al-Assad in Latakia.

The supply of Assads is not inexhaustible, and some at least of their followers must be wondering where they are taking them. This month’s defection of Manaf Tlas , a Republican Guard general, stripped away the regime’s last Sunni veneer. The Assads’ decision to unsheathe the sectarian knife, to corral Syria’s minorities into its camp, has destroyed the fiction that it is the vital antidote to Sunni extremism. As minority Kurds, Christians and Druze start drifting towards the opposition, this is now a straight fight between the Alawites and the Sunnis – and their foreign backers.

Iran and Russia have stood with the regime, but they cannot fight its battles. In the Sunni camp, Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Turkey have stepped up aid, with the US in the background. Rebel forces have gained momentum since late spring and have crystallised into provincial commands. How much fighting there is to come depends on the cohesion of a shrinking regime. Loyalist forces have over-run two districts of the capital after 10 days of fighting but meanwhile Aleppo, the commercial capital, has erupted. The Assads cannot be everywhere at once.

When they do fall, there is natural concern about what will replace them – especially since the Wahhabi Saudis and Qataris are directing their support towards the Islamist Muslim Brotherhood. Yet despite the regime’s slaughter of (mostly Sunni) civilians, and a few attested rebel atrocities, there have been no mass reprisals against the minorities. This suggests discipline and deliberation by opposition forces on the ground: the regional military councils and the local co-ordinating committees of activists driving the civic uprising. As in Libya, an international alliance against the Assads may have something to work with.

Turkey’s role could be important, especially if it can moderate Gulf influence on the Muslim Brotherhood and prevent Syria from being sucked further into the regional contest between Sunni and Shia. Russia may be useful in identifying elements of the present Syrian state that could serve as interlocutors on its future. An ultimatum from the Free Syrian Army, the rebel military umbrella, giving officers and officials until the end of this month to defect, may hasten that process.

It is natural to worry about what will replace the Assads, but not in a way that encourages them to fight on. Their 42-year tyranny was a known quantity in a dangerously volatile region. For nearly four decades not a shot was fired across the Golan Heights, seized by Israel from Syria in the 1967 Arab-Israeli war and secured against Syrian counter-attack in the 1973 war.

But this should not blind us to how the Assads are brutalising their people now, or make us forget what they did in Lebanon and Iraq before. They played divide-and-rule with and within Lebanon’s mosaic of sects during three decades of occupation. They provided the main pipeline into Iraq for Sunni jihadists to wage attrition against US occupying forces and to slaughter Shia civilians. Posturing as the “beating heart of Arabism” and the fulcrum of an axis of resistance to Israel and western designs in the region, the Assads’ Syria was always willing to fight to the last Palestinian or Lebanese. The job now is to hasten its end, not to mourn its passing.

Financial Times

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.