By: James Denselow

By: James Denselow

After over 450 days of protests and an estimated 15,000 reported deaths, there is no sign of Assad’s regime reasserting its control over Syria. Both the US and the EU have signalled their belief that the regime is in a death spiral and that it is only a matter of time before the endgame is reached, with United Nations Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon accusing it of having “lost its fundamental humanity.” However, the notion of military intervention is off the table. Not only are the Russians and Chinese preventing any movement from within the UN, but with less than 20 percent of their respective publics supporting military intervention, both Washington and London currently have no stomach for military action.

There is no sign of an imminent collapse of the regime, with defections from the military and ubiquitous secret police failing to reach a critical mass for a host of reasons, including the regime’s threat of retribution against defectors’ families. Syria’s armed forces remain strong, and are thought to number 325,000 regulars with more than 100,000 paramilitary personnel, not to mention the numbers of pro-regime Shabiha. The International Crisis Group (ICG) reported that while at “the outset of the crisis, many among the security forces were dissatisfied and eager for change; most are underpaid, overworked and repelled by high-level corruption. They have closed ranks behind the regime, though it has been less out of loyalty than a result of the sectarian prism through which they view the protest movement and of an ensuing communal defence mechanism.”

This leaves us with the prospect of continued conflict over the short to medium term. However, it is important to note that this scenario is not static, and that a ‘wildcard’ event could lead to either the current regime defeating the rebels, or to the regime being successfully overthrown. An internal, high-level coup or assassination, for example, could suddenly bring about an end to regime. In May, opposition elements reported that they had successfully poisoned several senior regime figures including General Hasan Turkmani, an assistant vice president, and Lieutenant General Mohamed Al-Shaar, the minister of the interior. Although the official Syrian Arab News Agency has called the assertions that they are dead “baseless,” the story is a reminder of how unexpected events can come into play. Indeed, reports of the regime preparing to use chemical weapons against the protesters could end opposition and be another catalyst for a change. In February, the opposition reported that Syria’s military had begun stockpiling chemical weapons and equipping its soldiers with gas masks near the city of Homs. A ‘Syrian Hallabja’ could force a new momentum on building a still non-existent appetite for intervention.

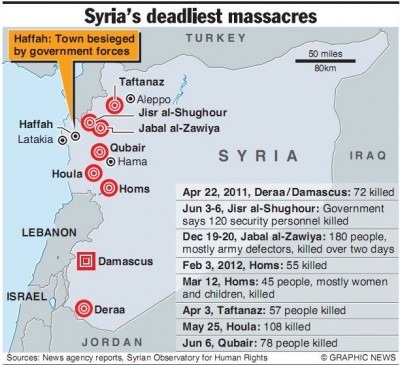

Despite a Chatham House paper speculating that a ‘Syrian Srebrenica’ massacre could act as a ‘tipping point’ for intervention, the reaction to the Houla and Qubair killings proved otherwise. Indeed, Kofi Annan has warned that “mass killings could become part of everyday reality in Syria.” There is also the prospect of unforeseen regional events, such as a third intifada in the occupied Palestinian territory or an Israeli attack on Iran’s nuclear facilities, which could lead to a host of ramifications.

The Syrian Opposition

The protest movement that began in March 2011 with the arrest of children drawing graffiti in Deraa can be characterised as a battle between courage and fear: the courage of people to come out onto the streets and denounce a regime that has ruled with the ‘hegemony of emperors’ for over 40 years, and the resentment against the violence that the regime has deployed as a means of ending protests.

One of the central arguments deployed by the Syrian regime is the false analogy that Assad is the state, and that without him the state would collapse or fragment along the Iraqi-Lebanese lines, complete with chaos and the arrival of Al-Qaeda. This argument is in evidence in all of Assad’s speeches and the ubiquitous posters of the president, often with the words ‘Syria, Assad’ underneath. The words imply that there is no alternative to Assad’s rule.

Meanwhile, the Syrian opposition is both geographically and politically fragmented. This is no surprise, given the lack of political oxygen allowed under the Assad dynasty’s control of the country. The nascent Syrian National Council (SNC), the Local Coordination Committees (LCC), the Free Syrian Army (FSA), the Muslim Brotherhood, various franchises inspired by Al-Qaeda, and more independent and organic opposition representing Kurds, students, villages, districts, suburbs, and more, can all be said to be part of the opposition to the Assad regime.

While the choice of a secular Kurd, Abdulbaset Sieda, as head of the Syrian National Council is an attempt to better unite the opposition efforts, significant challenges remain. There is a huge amount of international support for a more effective, representative and united opposition, with the ‘Friends of Syria’ contact group a testament to that. Ultimately, the greatest source of legitimacy for the opposition comes from their actions within the country. The Iraq model of an exiled opposition remains a lesson in how not to support an alternative to a regime. Of course, the difficulties of organising and operating whilst under constant attack from the regime means that it is a huge challenge for the opposition to present a united front. A recent meeting in Bulgaria in May attempted to set up a roadmap to create a common vision and a plan for coordination between a diverse collection of opposition groups, with the aim of developing a mechanism to work together under the umbrella of the SNC while maintaining their autonomy.

Scenarios for the Opposition

Offer an Inclusive vision

Despite the escalating violence in the country, there remains hope that the end of the Assad regime can deliver a new Syria that can better serve all of its citizens. At a recent debate in the British House of Lords, members of a panel were asked how they would ‘save Syria.’ However, instead of focusing on options going forward, debate focused on the role of the Syrian Kurds within the opposition, with one activist claiming that the “regime and the opposition are as bad as each other.” In order to avoid a post-regime situation characterised by massive internal division, similar to the situation in Libya with its 200 militias, the opposition must present a broad and inclusive vision of a new Syria.

Sending out a message of progressive inclusivity by adopting a new Syrian flag, rather than the old flag that was used for several decades in the last century, and opening a discussion on changing the name of the country from the ‘Syrian Arab Republic’ to the ‘Syrian Democratic Republic’ could offer a populist statement of intent that would particularly appeal to the Kurds, who comprise 10-15 percent of the population.

A report by the European Council of Foreign Relations (ECFR) warned that “so long as Syria remains a playground for these broader interests, the prospect of a united front geared towards ending the bloodshed remains remote at best.” The opposition must maintain a ‘Syria First’ strategy that avoids compromising the country’s interests in favour of those of outside powers, but publically explains how it will accept outside support.

Offer an Economic vision

An ICG report released in July 2011 stated that “over the past decade, conditions significantly worsened virtually across the board. Salaries largely stagnated even as the cost of living sharply increased. Cheap imported goods wreaked havoc on small manufacturers, notably in the capital’s working-class outskirts. In rural areas, hardship caused by economic liberalisation was compounded by the drought. Neglect and pauperisation of the countryside prompted an exodus of underprivileged Syrians to rare hubs of economic activity.”

Last month, the Syria Business Forum pledged $300 million towards the Syrian opposition. Wael Merza, secretary general of the opposition Syrian National Council, explained that the “fund has been established to support all components of the revolution in Syria, and to establish a strong relationship with businessmen inside and outside Syria and to protect civilians.”

The opposition should use such support as part of a package of economic pledges for the post-Assad era. Economic incentives could prove particularly attractive as international sanctions begin to bite. The Syria Report published an article highlighting how “the Ministry of Economy has reduced the average weight of a cooking gas cylinder to 10 kg but kept its price unchanged, in effect increasing its cost by some 16 percent, as it battles with continuous shortages.” Meanwhile, Syrian government figures put annual consumer price inflation at 31 percent in April, with residents saying that basic goods such as sugar, vegetable oil and eggs have doubled in price.

Offering an economic vision for the future for the country should focus on the neglected countryside and job creation. Pre-prepared trade deals with Turkey and the EU, the biggest infrastructure investment scheme in Syria’s history (supported by the Gulf), and joint energy ventures with the Russians and Chinese should allay their strategic fears. Economic plans should also offer a promise to end state corruption and cronyism, with the United Nations, perhaps through the UNDP, providing guarantors and independent government auditing.

Outline post-Assad de-Ba’athification

The opposition must learn from Iraq in planning a process of transition and reconciliation that follows the demise of the regime. Naming and shaming senior figures with blood on their hands whilst maintaining as broad an amnesty scheme as possible, and one that is well-publicised, is crucial. This could be an important mechanism in encouraging defections and a vital dynamic within the balance of power. Indeed, on 11 June the opposition reported the highest rates of defections within the ranks of the Syrian Army. Hundreds defected in the province of Idlib and the city of Homs, including a strategic air defence battalion armed with anti-air and anti-tank missiles.

Improve communications abroad

The opposition must understand the nature of conflict fatigue felt by the Western media and public and work creatively to ensure that events are kept on international agenda and high in public imagination.

Reporting from inside the country in June, Sky’s Tim Marshall described the opposition’s “increasingly sophisticated propaganda machine including the use of Skype and YouTube, while government officials rarely appear and rarely give … access to its military.” The FSA is running a rudimentary embedding process, although reports from Channel Four’s Alex Thompson about being deliberately led into a free fire zone show they still have much to learn. A more immediate action should be to appoint a spokesperson who can respond to the 24-7 global satellite media demands, preferably based in a location inside the country or along the Turkish border.

Meanwhile, expatriates and exiled Syrians continue to produce creative accounts of the situation with two highlights including the Top Goon: Diaries of a Little Dictator puppet show and the play, 66 Minutes in Damascus, which gave Londoners a vision of being under Syrian detention based on a series of first-hand accounts.

Avoid Sectarian Politics

A Conservative Middle East Council (CMEC) report earlier this year warned that “Syria is poised for sectarian conflagration—Allawites and Shia versus the Sunni majority with Druze, Christians, and other groups caught in the crossfire, or making tactical alliances.” The opposition must do its upmost to avoid a sectarian conflict, which would likely have a momentum of its own and fracture any post-Assad society. In his book, Sectarianism in Iraq, Haddad outlined how a perfect equilibrium is needed between state and sectarian nationalism that overlaps into different sects, allowing for a peaceful balance. In contrast, when state nationalism promotes one sect over another it often leads to sectarian tensions and violent clashes.

The opposition should outline an immediate plan for a post-Assad reconciliation process separated from any transition to democratic government.

Counter the Al-Qaeda threat

On 11 June, British Foreign Secretary William Hague told Parliament that “we … have reason to believe that terrorist groups affiliated to Al-Qaida have committed attacks designed to exacerbate the violence, with serious implications for international security.” The opposition will have to resist temptation to support, facilitate, or—even through inaction—help extremist groups. While they may offer a tactical incentive in attacks against the regime, they are accelerants of sectarian tensions and their presence allows the regime to defend the idea that the devil you know is preferable to the devil you don’t.

The Syrian Regime

The Syrian regime itself is running out of ideas. Authoritarian regimes traditionally use a balance of carrot-and-stick politics to maintain their rule, and the situation today is one in which the regime feels it has deployed more or less all of its carrots and is focusing entirely on different and more brutal uses of the stick.

ECFR Policy Fellow Julien Barnes-Dacey recently returned from a visit to Syria deeply pessimistic about the situation on the ground, with hopes for a political solution appearing all but dead: “The window of opportunity for a political solution now appears about a millimetre wide, with everything dependent on whether Annan can secure immediate, meaningful concessions from Assad—pretty much the only step that would bring the country back from the abyss. However, this is now a highly unlikely outcome—and not because the regime feels strong, but by contrast because it appears to feel weak.”

Assad’s ‘carrots’ have included more rights and citizenship for the Kurds, the end of the Emergency Law, the sacking of Parliament and new Parliamentary elections, constitutional change with new parties and reformed media laws, concessions to the Islamic community, and more. However, the problem is that Assad has lost so much legitimacy across the country that these offers have not significantly reduced or ended the protests, although they may have encouraged others not to stand up against the regime—a metric which is impossible monitor.

Meanwhile, the Annan Plan has proved to be the only game in town, with no sign of any of the participants actually playing. Although lethal violence is estimated by human rights groups to have dropped by 36 percent since the plan was supposed to come into effect, the Houla and Qubair massacres signalled the effective demise of the increasingly-strained likelihood of a ceasefire.

An ECFR report into possibilities for Syria’s future suggested that “Annan should encourage the opposition to enter a political process without the precondition of Assad’s departure.” Arguably, the one ‘carrot’ the regime has left is to open itself up to a Presidential election with independent monitors who can prove an unimpeded process and where opposition figures can stand; this, however, is unlikely.

Scenarios for civil conflict

With an absence of any political initiatives, the violence the state is deploying against the opposition is the only scenario left open to examination.

The language on civil conflict in Syria has become increasingly pessimistic over the past four weeks. Syria is on the brink of a “catastrophic” civil war that will spread beyond its borders with explosive consequences for the Middle East, senior United Nations figures have warned. UN envoy Kofi Annan said in June that “Syria is not Libya. It will not implode; it will explode, and explode beyond its borders.” Meanwhile, UN Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon commented that “Syria can quickly go from a tipping point to a breaking point. The danger of full-scale civil war is imminent and real, with catastrophic consequences for Syria and the region.” British Foreign Secretary William Hague explained that “we don’t know how things are going to develop. Syria is on the edge of a collapse or of a sectarian civil war, and so I don’t think we can rule anything out.” Radhika Coomaraswamy, the UN special representative for children in armed conflict, said after visiting the country that “rarely, have I seen such brutality against children as in Syria, where girls and boys are detained, tortured, executed, and used as human shields.”

There has been a proliferation of discussion over the semantics of civil war. The regime describes events as a battle against extremists, while the opposition explain their actions as part of a revolutionary uprising. Civil wars are rarely declared, but rather are entered into as a consequence of the failure of politics. As in Iraq and the Askari mosque bombing in 2006, triggers for civil war are often acknowledged in retrospect. The Syrian population are very aware of the consequences of ethno-sectarian civil conflict, having witnessed and borne some of the fallout of the Lebanese Civil War (1975-1991) and the Iraqi Civil War (2006-2008).

With these points in mind, there are two main options within the paradigm of continued violence:

Outside powers arm opposition fighters

At a practical level, what the opposition forces need is artillery and air support in rural areas, effective surveillance capabilities, and new weapons including better RPGs, anti-tank, portable mortars, and sniper rifles suited for urban fighting. There can be little doubt about the practical effect that this would have on the momentum of violence, potentially drastically increasing the numbers of casualties. This would lead to scarred cities, along the lines of Beirut and Fallujah, across the country. As the ECFR explained, “Expanding and supporting armed resistance would invite even wider violence.”

Outside powers fail to arm opposition fighters

In The Guardian, veteran Syria commentator Patrick Seale argued that “the only way to prevent a full-scale civil war in Syria…..is to demilitarise the conflict and bring maximum pressure on both sides to negotiate.” In June, The Guardian reported that there is no evidence of state-backed weapons runs in northern Syria, where Free Syrian Army units are mainly using small arms supplied by defectors or bought from still-serving loyalist troops. If the opposition fighters are starved of outside support they will be forced to rely on acquiring munitions from government forces and would likely adopt guerrilla tactics along the model of the Iraqi insurgency, typified by hit-and-run attacks on government forces and installations.

Conclusions

The tragedy of the situation in Syria today is the general consensus that the situation will continue to deteriorate for the short to medium term. The international mechanisms of diplomacy are gridlocked, while the actors on the ground continue to lock horns in an increasingly bloody war of attrition with innocent civilians suffering the most casualties. Despite the grim backdrop, the Syrian opposition retains the momentum to offer a new vision and new options for the country. To do this requires real statesmanship to unite and present a coherent and persuasive narrative that the people can get behind. Meanwhile, the regime, bereft of creative and peaceful means to placate the protests, is trapped in a zero-sum game of raising the levels of violence directed against their own cities and citizens.

James Denselow is the Director of the New Diplomacy Platform and Middle East Security Analyst based at Kings College London.

Majalla.com

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.