By Ian Bremmer

By Ian Bremmer

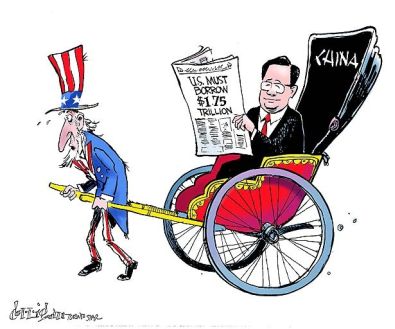

Drawn-out wars, economic struggles, exploding debt — it’s easy to point to these signs and conclude that America is in an irreversible decline; that after a good run, it’s time to hand the superpower baton to China or some other up-and-comer. Certainly, America faces big challenges, and it’s true that, economically, the United States was better off a decade ago.But those seeing decline as inevitable do not just ignore the nation’s history of resilience, they also misread the facts on the ground. America’s decline is a myth — and here are five common misconceptions worth dispelling.

1. The United States is no longer a superpower.

Certainly, countries such as China and Russia have more power than ever to obstruct U.S. foreign policy goals; their United Nations veto against intervention in Syria is one recent example. And the United States is increasingly unwilling to play the role of global cop, as it pares back its presence in the Middle East and fights over significant possible cuts to its defense budget because of Capitol Hill’s failure to reach a debt deal.

Even so, the United States is still the world’s only superpower, and so it will remain for the foreseeable future. Its economy is more than twice the size of second-place China’s. Only America can project military power in every region of the globe: It has a military presence in more than three-quarters of the world’s countries and spends more each year on defense than the next 17 nations combined. This security role lets Europe and Japan spend less on defense and more on other priorities. The U.S. Navy safeguards important trade routes, enabling global commerce, while American aid bolsters poor and disaster-stricken states.

2. America’s economic future is bleak.

Part of the reason the United States is less willing to engage abroad is because it has its hands full with economic concerns at home: spiraling federal debt, high unemployment, lower wages and a growing disparity of wealth.

But while the U.S. economic outlook may not shine as bright as it once did, it is hardly grim. America’s higher education system is unparalleled, with a record 725,000 foreign students enrolled at U.S. universities last year. No country has a greater capacity for technological breakthroughs: The United States is the destination of choice for aspiring entrepreneurs, it’s the research and development center of the world, and Silicon Valley’s start-ups and venture capitalism are exemplary.

On energy, innovation in unconventional oil and gas resources has been the biggest game-changer of the past decade, with U.S.-based companies leading the charge. The United States is now the largest natural gas producer in the world. It is also the world’s largest food exporter, giving America some leverage against food price shocks or shortages.

Demographically, the United States is better off than other large economies. The U.S. population is expected to rise by more than 100 million by 2050, and the labor force should grow by 40 percent. Compare that with Europe, where the population is slated to shrink by as much as 100 million people over the same span, or to China, where the labor force is already contracting.

3. America’s political system is broken.

Gridlock in Washington makes all of America’s problems seem even more intractable. Many believe that Congress is too divided to ever pass meaningful legislation again. But let’s not forget that the first two years of the Obama administration saw more significant legislation passed — such as the stimulus, the health-care overhaul and the Dodd-Frank financial regulatory reforms — than any period since the mid-1960s. Whether or not you like the direction in which Obama took the country, the system is hardly broken.

Nor did the debt-ceiling debacle prove that U.S. politics is fractured for the long term. In fact, it showed the opposite. After the nation’s credit rating was downgraded, markets flocked to the U.S. dollar and Treasury bills, confirming America’s role as the world’s true safe haven — even if the crisis was caused by America itself. Economic uncertainty seems to only strengthen the dollar’s status as the world’s reserve currency.

We see political theater on Capitol Hill precisely because America is not in decline; unlike Europe, our back is not against the wall. Unfortunately, it often takes a crisis for the political system to fire on all cylinders, but if that time comes, politicians will rise to the task. And the markets know it.

4. The United States will give way to a rising China.

For all its progress in recent decades, China has to undergo daunting reforms to set itself on a path to becoming a modern, middle-class power. Even Premier Wen Jiabao has admitted that his country’s growth model is “unstable, unbalanced, uncoordinated and unsustainable.”

For all its progress in recent decades, China has to undergo daunting reforms to set itself on a path to becoming a modern, middle-class power. Even Premier Wen Jiabao has admitted that his country’s growth model is “unstable, unbalanced, uncoordinated and unsustainable.”

Here’s why: China, despite its increasing clout, is still a relatively poor economy, its growth fueled by plentiful cheap labor. This resource is problematic. As China continues to grow and moves up the value chain to produce higher-end goods, wages will not remain low. And labor will not just be costlier — it will also be scarcer. As a result of the Mao-era birth rate spike in the 1960s, followed by the one-child policy starting in the 1970s, China faces the double-edged sword of a growing senior population and a shrinking labor force to support the elderly. The ratio of Chinese workers to retirees is around 6 to 1 today, but by 2040, that number is expected to shrink to 2 to 1.

Finally, imagine a world in which a poorer country such as China becomes the world’s largest economy. The Chinese government’s willingness to lead on issues such as climate change and nuclear non-proliferation would probably pale in comparison with the leadership America provides today — yet one more reason Beijing will not supplant Washington anytime soon.

5. The world no longer needs U.S. leadership.

America’s global role is changing, and Washington, while still the lone superpower, has less clout. But ironically, the emergence of other contenders has made demand for U.S. leadership even stronger. This is clearest in Asia, where nearly all of China’s neighbors are reaching out to Washington for closer political and security ties.

After all, where else can they look? China’s growth is unpredictable, and Europe will be busy saving its single currency and the euro zone for years.

We are entering what I call the G-Zero: a period when global leadership goes by the wayside. It’s a less productive, more crisis-prone world, but it’s less painful for the United States than for everybody else. If America can engage the world with a narrower, self-interested focus, it will reap rewards. It will have the luxury of applying cost-benefit analysis before intervening abroad. It’s a downsized role, but don’t mistake this for decline.

Ian Bremmer is president of the Eurasia Group and the author of “Every Nation for Itself: Winners and Losers in a G-Zero World.” Follow him on Twitter: @ianbremmer.

Washington Post

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.