AS I walk around the streets of Beirut, that verse from “The Sounds of Silence” keeps rattling around in my head: “The words of the prophets are written on the subway walls, and tenement halls …”

AS I walk around the streets of Beirut, that verse from “The Sounds of Silence” keeps rattling around in my head: “The words of the prophets are written on the subway walls, and tenement halls …”

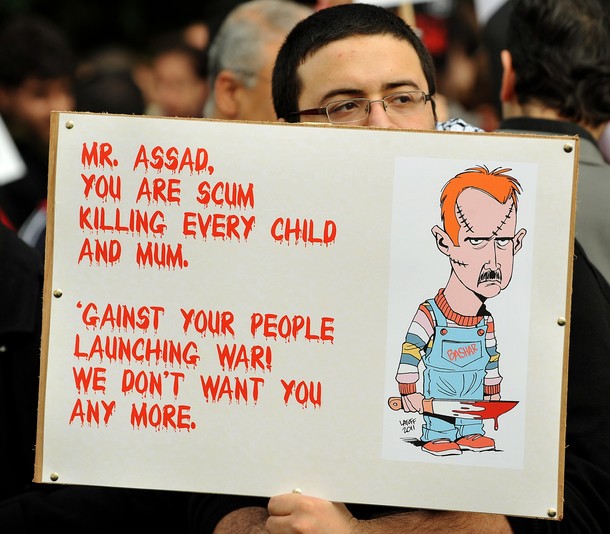

There is a highly revealing graffiti war going on here pitting opponents of Syria’s president, Bashar al-Assad, and his Lebanese ally, the Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah, on one side and their Lebanese and Syrian supporters on the other. Assad and Nasrallah have long called themselves “the resistance” to Israel, using that to build their legitimacy and to justify arming themselves against their own people. What is stunning to me is how much their masks have now been ripped off by their own people. It is written on the tenement walls around Beirut. The latest collection includes slogans like “The resistance is only resisting our freedom,” or Assad’s picture above the words “Step here” and “The one who kills his own people is a traitor.”

Both Assad and Nasrallah still have their sectarian followers, but outside of that shrinking circle they have lost the aura they cultivated from “resisting Israel.” Now both men stand naked before the Arab world for all to see — one using arms to “resist” the will of many Syrians and the other to “resist” the will of many Lebanese. Their people are no longer afraid to openly mock them.

Hanin Ghaddar, a rising young Lebanese Shiite journalist, last week wrote an open letter to Nasrallah published by the popular NOWLebanon.com, saying, “You were the brave hero who vanquished the Israeli Army in 2006 and brought dignity back to the Arabs. But you know what? These glorious days are over, and the word ‘dignity’ has now gained a new definition. It has nothing to do with your sacred arms and glorious victory. It is now about the power of the people on the street and their fight against their dictators. … Let us imagine this far-fetched scenario. When the uprising broke out in Syria, let’s say you came out in full support of freedom, or at least clearly asked the Syrian regime to refrain from using violence against the protesters. Can you imagine how popular and loved you would have been today? The Syrian people, from all sects, had photos of you hanging in their shops and homes after 2006. Today they burn your pictures on the streets. They hate you. The Syrian people hate you. The Egyptians, Tunisians, Libyans and many other Arabs hate you, because you support a tyrant who is killing his own people.”

But what to do about Syria’s uprising? Let’s start by putting it in historical context. What is happening in Syria, and across the Arab world today, is the first popular movement since the late 19th and early 20th century that has not been animated by foreign policy or anticolonialism or Israel or Britain. Instead, says Paul Salem, the director of the Carnegie Middle East Center in Beirut, “it is about us and our jobs and accountable government. … It is a profound reorientation to domestic priorities and pragmatism. It is a quest for dignity,” emerging from the bottom up.

The Syrian uprising, it is crucial to remember, began as a nonviolent protest by young men over corruption in the Syrian town of Dara’a, for which they were brutally tortured. It stayed remarkably nonviolent, nonsectarian for months, under the slogan “Silmiya, Silmiya.” (Or Peaceful, Peaceful.) It was deliberately turned into a civil war by Assad. Syrian opposition activists here in Beirut make clear that Assad opened fire on unarmed demonstrators, hoping to provoke a violent backlash. Then he could argue that this was not a peaceful democratic revolt but a sectarian revolt by Syria’s Sunni Muslim majority, aimed at ousting Assad’s ruling Alawite/Shiite minority and its allies. To some degree, it worked: Now we have a democratic struggle intertwined with a sectarian one.

This is why some Lebanese and Syrian activists here believe that — though it’s a long shot — it is still worth giving time for the U.N. envoy Kofi Annan’s effort to consolidate a cease-fire and put 300 Arab observers inside Syria, because it might create the space for the nonviolent, nonsectarian, democratic protests to re-emerge. These are the real threat to the regime. It may take longer, but remember: The bloodier and more sectarian the fight to depose Assad gets, the more deformed, violent and Islamist-dominated the post-Assad regime will likely be — and the more the civil war there will spread to Lebanon, Turkey, Jordan or Iraq. That is why just arming the Syrian opposition and standing back is a bad idea.

If the Annan plan fails, then the West, the United Nations and the Arab League need to move swiftly to set up a no-fly zone or humanitarian corridor — on the Turkish-Syrian border — that can provide a safe haven for civilians being pummeled by the regime and send a message to the exhausted Syrian Army and residual supporters of Assad that it is time for them to decapitate this regime and save themselves and the Syrian state. The quicker Assad falls, the less sectarian blood that is shed and the more of the Syrian state that survives, the less difficult a difficult rebuilding will be.

“Everyone expects these Arab revolutions to solve the problems, but what they are actually doing is revealing the existence of all these problems that were put in a freezer,” the Arab commentator Hazem Saghieh told me. “All these years, the only thing that was allowed to come to the surface was that there is a consensus on the beloved leader and animosity to Israel and imperialism. There was no room for politics and differentiation. Behind this facade, Arab society became rotten, and now we are seeing the return of the repressed.”

It’s like a kid who was beaten and left uneducated by his parents for 50 years and one day the kid finally decides to fight back, he added. “Morally, you have to support his right to revolt, but this guy is very traumatized.”

So let’s help in an intelligent, humane way, but with no illusions that this transition will be easy or a happy ending assured.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.