BY MITCHELL PROTHERO

The blacked-out sport utility vehicles entered the small mountain village of Arsal, in the furthest reaches of Lebanon’s Beqaa Valley, at midnight on a cold night late last month. The mostly Sunni residents of the town immediately knew what was happening: Hezbollah had come to grab someone from his bed.

The target appears to have been a Syrian relative of the dominant local tribe, the Qarqouz, who had taken refuge in the village, which lies just a few miles from the Syrian border. With close families ties on both sides of the line, as well as a central government presence that doesn’t even live up to the designation of “weak,” the tribes make little distinction between Syria and Lebanon, and many make their livings plying that most cliché of all Beqaa trades: cross-border smuggling.

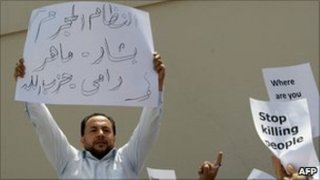

Whether the wanted man is a dissident Syrian remains unclear — the family certainly denies any such thing. Nevertheless, the raid by Hezbollah’s internal security apparatus follows a pattern of harassment, kidnapping, and cross-border rendition of Syrian anti-regime activists by Syria’s many loyalists in Lebanon, which also include rogue police units, pro-Syria political movements, and even Kurdish separatists. As President Bashar al-Assad looks to squelch an astonishingly persistent nine-month revolt, Lebanon is fast becoming another battleground between supporters and opponents of his rule.

The Arsal incursion, however, did not go how Hezbollah planned. The men in black trucks didn’t impress the residents of Arsal: True to their reputation as a flinty bunch, the tribes immediately sent out men bedecked with the ubiquitous accessories of any respectable Beqaa smuggler — the AK-47 and rocket propelled grenade launcher — and ambushed the convoy before it could lay hands on the purported Syrian fugitive.

Local officials released a statement shortly afterwards, warning Hezbollah against any attempt to repeat its adventure. “Let everyone know that Arsal is not orphaned,” it read. “[A]nyone attacking Arsal or any other Lebanese town would be definitely serving the Zionist enemy and Assad’s brigades.”

Hezbollah, which tepidly denied the incident, hasn’t released any casualty figures, but the ensuing firefight was nasty enough that the Lebanese Army dispatched a team to extract the Hezbollah men from the ambush — and itself came under fire from Sunni mountainfolk with little use for either Shiite militant supporters of the Assad regime, or law enforcement of any sort.

The Lebanese army claimed in a convoluted statement the next day that an intelligence unit was in hot pursuit of a known criminal when it unexpectedly came under attack. However, that narrative unraveled over the next few days, when a collection of local officials and anti-Syrian Sunni politicians accused Hezbollah of instigating the attack — a claim confirmed to FP by multiple intelligence and law enforcement officials, as well as one prominent human rights activist.

This latest incident is just the latest example of how the Syria revolt has spilled over onto Lebanese soil, threatening to destabilize the already fragile country. Over the last few months, as the protest movement has waxed and waned, Syrian troops have repeatedly crossed into Lebanese territory, breaching a frontier they never really respected in the first place, and laid land mines along their shared border in a bid to stop smugglers and deter both refugees from leaving and armed opponents of the regime from mounting operations.

In the Hezbollah-dominated southern suburbs of Beirut, which is full of Syrians who have come to Lebanon for economic or political reasons, there is a noticeable chill as people try to avoid getting caught in the crossfire of Syria’s war.

“If you’re being arrested by men in blacked-out SUVs or vans, you’re being arrested by Hezbollah,” according to one Shiite Lebanese resident of southern Beirut who lives near Hezbollah’s “security zone,” which houses headquarters buildings and the families of top officials. “Even [military intelligence] guys have to have license plates on their cars and identify themselves. But ‘the resistance’ doesn’t need to bother. No one in Lebanon can touch them for murder of a prime minister — ask the special tribunal — so do you think they worry about traffic tickets, or kidnapping a Syrian? No one would dare question them.”

Like virtually everything else in this divided country, which narrative a particular Lebanese believes is directly tied to their political allegiances. For Hezbollah and other Syrian regime allies, Assad is battling a truly complex alliance of al Qaeda and Sunni fundamentalists –sponsored by the Americans and Israelis. Assad’s opponents, on the other hand, hold that the Lebanese government has been cowed by threats of a Syrian invasion if it doesn’t help crush dissent in the rural safe havens along the border.

Lebanon’s Defense Minister Fayez Ghosn, a Hezbollah ally, announced on Dec. 21 that Arsal had become an al Qaeda safe haven, drawing bitter denials from the village’s mayor and tribal elders, who pointed to months of local farmers being shot by Syrian troops for tending fields along the border, Syrian troops incursions, and of course, last month’s Hezbollah-led debacle.

For anti-Assad dissidents in Lebanon, even more ominous than the Arsal raid is the growing evidence that they are not even safe from Assad’s long reach in the capital of Beirut.

The illegal abduction of three Syrians in February from the parking lot of a police station – where they were then transported over the border and turned over to Syrian intelligence – confirmed many Lebanon-based Syrians’ worst fears.

Jassim Jassim, one of the hundreds of thousands of day laborers who make their living working in Lebanon, had been arrested briefly by the Lebanese police for handing out flyers calling for the end of Assad’s regime, according to police officials who investigated the incident. Shortly after his arrest, Jassim, a Sunni from Homs, called his brother and brother in-law to say he would be released shortly and they should come to the station in the Beirut suburb of Baabda to pick him up.

Hours later, after none of the men returned, Jassim’s wife called his mobile phone. A man speaking in a Syrian accent answered, and informed her that the three men had been taken “home.” They’ve never been heard from again.

An investigation by the head of Lebanon’s Internal Security Forces (ISF), Brig Gen. Ashraf Rifi, a supporter of former Prime Minister Saad Hariri from Tripoli, discovered that the three men were thrown into an SUV with ISF markings in the police station parking lot. Even more disturbingly, the driver was later indentified as Lt. Saleh al-Hajj, the head of the ISF protection detail at the Syrian embassy in Beirut.

According to a police officer assigned to the embassy protection team who has worked with Hajj in the past, it is widely known that Hajj works closely with Syrian intelligence. His father, Ali al-Hajj, was a top Lebanese intelligence official under the Syrian occupation and one of four top security officials detained for years on suspicion of plotting the murder of Saad Hariri’s father Rafiq, also a former prime minister. However, because of Lebanon’s diverse mosaic of loyalties and patronage, there is nothing even the head of the police can do to rein in such rogue operators.

“Everyone in the [police] works for some faction or party,” the young officer explained. “The corruption is bad enough, but it’s the politics that can get you killed. Sometimes I think everyone I work with has two commanders — his police commander and his political commander: Syria, Iran, Saudi Arabia. Some people have even turned out to work for the Israelis. It’s a catastrophe for Lebanon.”

Other dissidents have gone missing as well, and still more have fled the country after receiving warning that their names have appeared on a hit list of anti-regime targets being sought by Syria’s Lebanese allies.

“[T]he Syrians have a long arm in Lebanon,” according to Rami Nakhle, a prominent Syrian dissident who was based in Lebanon at the start of the uprising but was eventually forced to flee to the United States after being warned his name was on a list for assassination or kidnapping held by Hezbollah and other Syrian-aligned groups.

Another activist, who remains in Lebanon but asked not to be identified for safety reasons, said that sympathetic members of the Lebanese intelligence services have done their best to protect them, but due to the influence of Hezbollah and remnants of Syrian intelligence in Lebanon, “often the best they can do is warn us when our name comes up for elimination.”

Hezbollah, for its part, denies involvement in anything sinister. One Hezbollah internal security official interviewed by FP admitted that his teams were hunting Syrian dissidents, but denied kidnapping peaceful demonstrators.

“We’re looking for weapons dealers, al Qaeda members, and those who would destabilize Lebanon,” he said. “It’s like when the Iraqi refugees first started coming here in 2004. We had to closely monitor them to make sure they were safe. But we don’t kidnap people and if we arrest them, we turn them over to the Lebanese authorities for prosecution.”

The claim that Hezbollah is only targeting weapons dealers or terrorists runs into some basic mathematical problems. One Lebanese intelligence official said the number of actual weapons smugglers or al Qaeda-types arrested “might reach 10. Maximum.” Meanwhile, dozens of Syrians in Lebanon have reported harassment or arrest, and even in some cases been victims of disappearances.

The situation has put the professionals in the Lebanese military and intelligence services in a bind. Nobody these days envies the position of Prime Minister Nijab Miqati, who is attempting to balance the interests of the pro-Syrian political bloc that brought him to power with the beliefs of his own Sunni constituency, which is outraged by Assad’s brutality. In an effort to heal Lebanon’s social and political fabric — which was fraying even before Syria started to self-immolate — Miqati has worked overtime to appear as neutral as possible without infuriating either Hezbollah or the ruthless Syrian regime next door. His government has backed the Syrian regime at the Arab League, but has also not entirely squelched Syrian refugees’ freedoms in Lebanon.

One consistent fear is that Syria, which blames Lebanon’s predominantly Sunni northern city of Tripoli and its outlying rural areas for fomenting much of the unrest, might become even more emboldened and expand its operations beyond small-scale raids in an attempt to halt the Syrian rebels’ flow of support.

The Lebanese military recent cut off access for journalists and non-residents to the area of Wadi Khaled, north of Tripoli, where as many as 5,000 Syrians have taken refuge. The area is also a hotbed of rebel support, and even sympathetic Lebanese officials are terrified that Syria might escalate the conflict there.

“We have to [take these steps],” one exasperated military intelligence official said in an interview. “Even if you sympathize with the Syrian people, and many of us do, we can’t allow Lebanon to go down the same path.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.